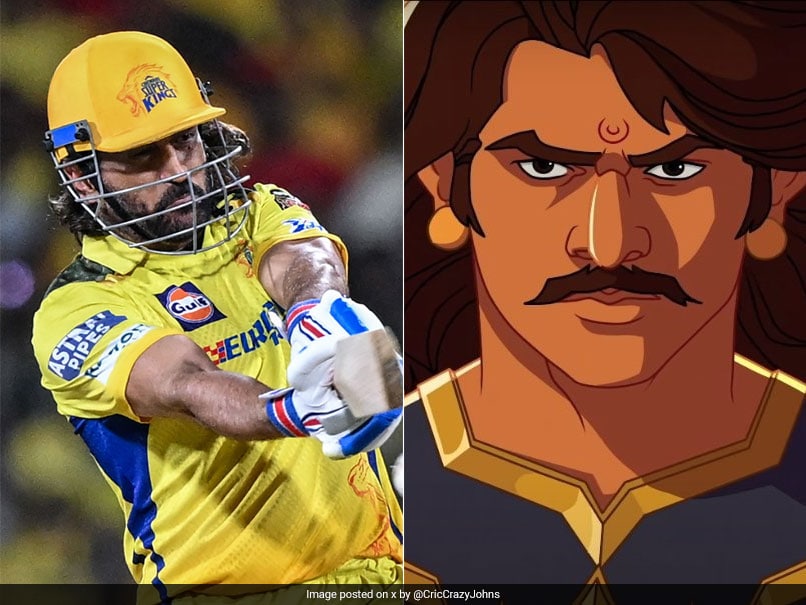

Little room: Jacinter Awino holds her son as she cleans utensils in the Kibera slum of the capital Nairobi in Kenya.A

| Photo Credit: AP

In the heart of the crowded Kibera neighbourhood in Kenya’s capital, Jacinter Awino shares a small tin house with her husband and four children. She envies those who have escaped such makeshift homes to more permanent dwellings under the government’s affordable housing plan.

The 33-year-old housewife and her mason husband are unable to raise the $3,800 purchase price for a one-room government house. Their tin one was constructed for $380 and lacks a toilet and running water. “Those government houses are like a dream for us, but our incomes simply don’t allow it,” Ms. Awino said.

The government plans to build 2,50,000 houses each year, aimed at eventually closing a housing deficit that World Bank data puts at two million units. The plan was launched in 2022, but no data is available on the number of houses already completed.

Lack basic needs

Kenya’s urban areas are home to a third of the country’s total population of more than 50 million. Of those in urban areas, 70% live in informal settlements marked by a lack of basic infrastructure, according to UN-Habitat.

Some urban Kenyans have moved into a government housing project on the outskirts of the capital, Nairobi, where one-bedroom units sold for $7,600 last year.

Felister Muema, a 55-year-old former caterer, paid a deposit of about 10% through a savings plan and is expected to pay off the balance in 25 years. “This is where I have started living my life,” she said. “If I do something here, it is permanent. If I plant a flower, no one is going to tell me: ‘Uproot it, I don’t want it there.’ This gives me life.”

But experts say construction and financing need to change and speed up for Kenya’s housing deficit to be met.

“We cannot rely on the traditional mortgage route,” said UN-Habitat’s head of East Africa, Ishaku Maitumbi, who recommended a cooperative savings system that is popular with Kenyan businesses.

For home construction, some are exploring the emerging technology of 3-D printing. A machine layers special mortar to form concrete walls and cuts the building time by several days compared to traditional brick and mortar work.

A company, 14Trees, has used the technology to build a showcase house in Nairobi and 10 houses in coastal Kilifi County.

Company CEO Francois Perrot said the technology can help address the huge housing need on the African continent, but it will take time. “If we want to clear that backlog, we need to build differently, we need to build at scale, with speed, and with low-carbon materials, and this is what construction 3-D printing makes possible,” Mr. Perrot said.

Design, price

The company’s homes, like many traditionally built ones, remain beyond the reach of most Kenyans.

A two-bedroom house costs $22,000 and a three-bedroom one costs $29,000. But Mr. Perrot asserted that acquiring a printer locally and making mortar locally would help bring down costs.

“People don’t really worry or care about technology. What they care about is the design, the price, the way it is set up, the layout of the building,” he said.

Nickson Otieno, an architect and founder of Niko Green, a sustainability consulting firm, said such new technology has great potential but remains limited. “It will still take a long time for it to compete with brick and mortar,” he said. “Brick and mortar, everybody can build their house anywhere they are. They are able to access the materials, they are able to access the tradesmen who build the house and they can plan the cost.”