Reminders that Covid-19 has not gone away pop up from time to time, even if the world seems to have moved on. More than 40 athletes at the 2024 Olympics in Paris have tested positive, highlighting a new global rise in cases, the World Health Organization (WHO) said on August 6. And now, the subgenus Sarbecovirus, of which SARS-CoV-2 is a member, is on the list of ‘priority pathogens’ in the WHO’s recently-released ‘Pathogens Prioritization’ report.

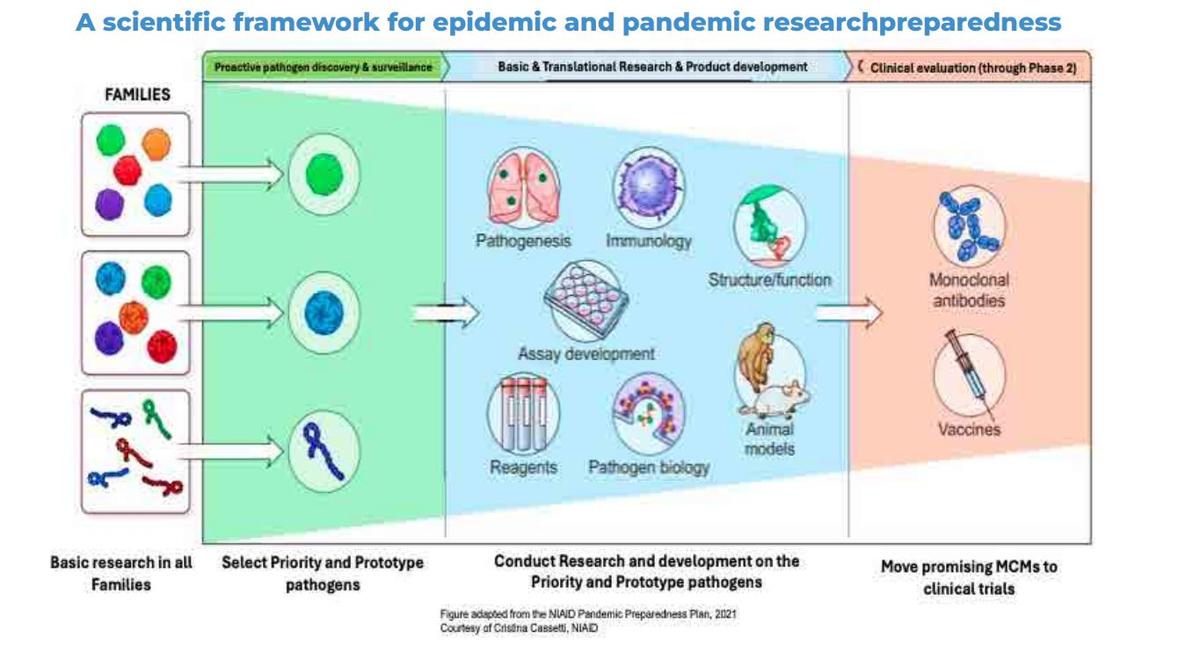

The report, which is a framework for epidemic and pandemic research preparedness, is the result of work that began in late 2022, involving over 200 scientists from 54 countries who evaluated the evidence related to 28 viral families and one core group of bacteria, encompassing 1,652 pathogens. The final list comprises over 30 ‘priority pathogens’.

Sarbecovirus is classified as ‘high’ in the WHO list, for its risk of causing a Public Health Emergency of International Concern or PHEIC. The list also includes Subgenus Merbecovirus, which includes the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV). Both MERS-CoV and the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) virus were also listed in the 2017 and 2018 WHO reports, but not their entire subgenuses.

On the list of priority pathogens, but not a new addition, is another virus that India has been dealing with of late: Nipah, a 14-year-old boy died at the Government Medical College Hospital, Kozhikode, Kerala, after contracting it. Both Ebola and Zika virus too, feature on the list, as they did in 2018, with both classified as ‘high’ for a Publuc Health Emergency of International Concern or PHEIC risk. Maharashtra is currently grappling with a Zika virus outbreak – reports indicate there have been over 70 cases of Zika in Pune in the past two months and these include 26 pregnant women.

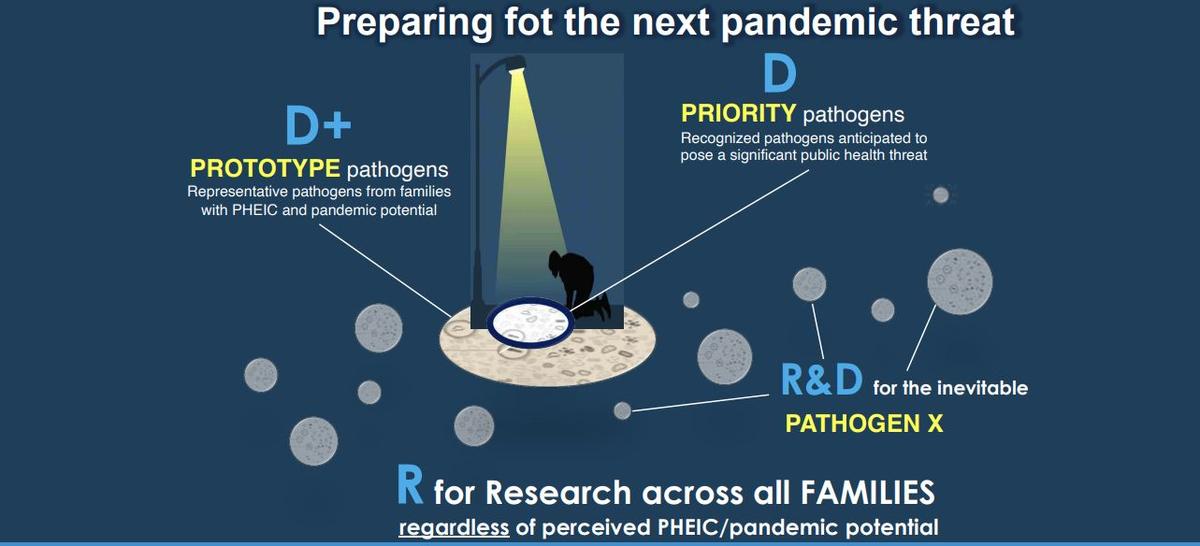

Imagine scientists and public health officials as individuals searching for the “lost keys” (the next pandemic pathogen). The area illuminated by the “streetlight” represents the Priority Pathogens. We can expand the lighted area a bit by researching the Prototype Pathogens and using them as pathfinders within Families to expand our knowledge and understanding. Neglecting the “Dark Areas” is not advisable given the uncertainty about which pathogen will indeed cause the next PHEIC or pandemic.

| Photo Credit:

WHO, Pathogens Prioritization, June 2024 report

The list of priority pathogens, says Chennai-based infectious diseases specialist Subramanian Swaminathan, is a pointer towards the pathogens that governments could allocate resources towards, for surveillance and medical countermeasures. This does not mean all of them are currently a problem, he says, but it means that countries have to monitor these pathogens as they have the potential to turn into a problem.

“Surveillance of these pathogens has to involve multiple aspects – is the pathogen spreading beyond a geographical area, is it becoming more virulent, is its transmissibility increasing, is the clinical manifestation of the disease it causes changing, is it becoming more resistant to known treatment and does it have vaccine escape properties – all of these aspects have to be monitored,” he says.

What else is new on the list? The dengue virus and the influenza A viruses, including the H5 subtype, which caused an avian influenza outbreak in India and which even affected cattle in the United States are now on the list, along with mpox, which has currently erupted in parts of Africa.

Among bacteria added to the list are those that cause plague, cholera, pneumonia, dysentery and non-typhoidal salmonella, a key cause of diarrhoeal diseases.

It may be recalled that early this year, the WHO had updated the Bacterial Pathogens Priority List (BPPL) and this had included gram-negative bacteria resistant to last resort antibiotics, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis resistant to the antibiotic Rifampicin. The list had featured 15 families of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

In the Southeast Asia region, the report notes, bacterial pathogens are priorities including Vibrio cholera O139 (cholera) and Shigella dysenteriae serotype 1 (dysentery). Priority pathogens Henipavirus nipahense (Nipah) and Bandavirus dabieense (causes severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome) are endemic it said, as are the mosquito-borne Orthoflavivirus denguei (dengue) and Zikaense (Zika virus disease), and Alphavirus chikungunya.

Resources, says Priscilla Rupali, senior professor & head, Department of Infectious Diseases, Christian Medical College, Vellore, need to be focussed on diseases of high mortality that have pandemic potential such cholera, Nipah, dengue and Zika. For other diseases that cause a fair bit of morbidity such as chikungunya, and shigella etc., surveillance to predict epidemics is important, Prof Rupali notes.

The report, says Abdul Ghafur, consultant infectious diseases, Apollo hospitals, Chennai, has on its list some diseases that India is already aware of and grappling with including Nipah, Zika and dengue. “What we need is more data and more research, but crucially, more low-cost diagnostics for priority pathogens. The Indian government needs to support start-ups to develop such diagnostics for these pathogens,” he says.

Prototype pathogens

The 2024 report, incorporates for the first time, the concept of the ‘Family approach’ and the ‘Prototype Pathogen’. The family approach, says Dr. Swaminathan, is important, as pathogens within a family have a lot of similarities, and even share genetic material, meaning an existing treatment option or vaccine for one strain of the pathogen family could potentially be repurposed for another. “By prioritizing research on entire pathogen Families as opposed to a handful of individual pathogens, this strategy bolsters the capability to respond efficiently to unforeseen variants, emerging pathogens, zoonotic transmissions, and unknown threats such as ‘Pathogen X,’ the report states.

The ‘prototype pathogens’, the report says, are “representative pathogens within a family selected to serve as a model for fundamental research” to develop medical countermeasures that can be applied to other members of the family.

As the report notes, the global health landscape is subject to constant evolution, with the potential emergence of new pathogens and evolution in the threat levels posed by existing ones: it emphasises the critical necessity for investments in research, development, and innovation on an international scale.

For the full report, click here.

(Zubeda.h@thehindu.co.in)