The retirement of Justice Umar Ata Bandial as the 28th Chief Justice (CJ) of Pakistan’s Supreme Court on September 16 brings to a close one of the murkiest chapters in the history of an institution which has remained blemished due to its cyclical bouts of adherence to, or resistance against, the doctrine of necessity.

Law of necessity

According to Henry de Bracton, a 13th century medieval jurist, the doctrine of necessity means “that which is otherwise not lawful is made lawful by necessity”. In Pakistan, this doctrine was first used in the Federation of Pakistan versus Maulvi Tamizuddin Khan case (1955), when the Federal Court of Pakistan (now the Supreme Court) headed by CJ Muhammad Munir upheld Governor General Ghulam Muhammad’s dismissal of Prime Minister Khawaja Nazimuddin’s government. Maulvi Tamizuddin Khan, president of the Constituent Assembly, had challenged the Governor General’s actions in the Sindh High Court, which struck down the Governor General’s order.

Thereafter in 1958, through the Dosso versus Federation of Pakistan, the Supreme Court upheld Dosso’s conviction for murder under the Frontier Crimes Regulation, 1901 (FCR), even though the Lahore High Court had ruled that the FCR did not fall under the 1956 Constitution. Martial law imposed by President Iskander Mirza was indirectly validated. In the Asma Jilani versus State of Punjab case 1972, Justice Hamoodur Rahman held Yahya Khan’s martial law as illegal. Asma Jilani Jahangir was a famous human rights activist in Pakistan. This paved the way for the restoration of democracy in the country.

However, in the Begum Nusrat Bhutto versus Chief of the Army Staff case in 1977, the Supreme Court validated the imposition of martial law under the doctrine of necessity. The pattern was repeated over the Junejo government dismissal in the Haji Saifullah case, 1988 and in the sacking of the Benazir government by President Ghulam Ishaq Khan in August, 1990 (Ahmed Tariq Rahim versus Federation of Pakistan).

The practice also emerged of martial law dispensers getting judges to swear fresh oaths of allegiance under Provisional Constitutional Orders (PCOs), so that they would enable the disruption of constitutional provisions. Only a few ‘braver’ judges dissented. Therefore, there were PCO judges and non-PCO judges in different political regimes.

The impact of the lawyers’ movement

In March, 2007, Chief Justice Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry defied the orders of General Pervez Musharraf, President of Pakistan and Army Chief, after which he was summarily dismissed over misconduct and corruption charges connected to his son, Arsalan. Mr. Chaudhry’s cause was taken up in a countrywide lawyers’ agitation which led to his reinstatement two years later. Much has been made of this milestone in Pakistan’s judicial history, signifying a standing up against the military establishment. However, Mr. Chaudhry’s tenure as CJ brought in other malpractices like discriminatory and arbitrary appointments, based on personal loyalties.

The military establishment continued to play a role in the decisions of the judiciary. In April 2017, once the Army decided to get rid of sitting Prime Minister, Nawaz Sharif, CJ Saqib Nisar disqualified him from holding public office for life in the Imran Ahmed Khan Niazi versus Muhammad Nawaz Sharif case, otherwise known as the Panamagate case, over non-disclosure of an iqama (fee agreement). The legal soundness of this judgment has remained questionable. Moreover, Mr. Nisar’s unwarranted forays into health management or creation of a fund for building dams has also raised eyebrows.

An attempt was again made in November, 2019 when CJ Asif Khosa set the cat among the pigeons by making several disparaging remarks on the proclivity of generals to give themselves ‘year after year’ of extensions. Describing his order as an ‘exercise in judicial restraint’, Mr. Khosa suspended the extension given to General Qamar Javed Bajwa as Army Chief by Prime Minister Imran Khan earlier in the year. He also extracted an undertaking from the Attorney General to amend laws pertaining to the Army Chief’s appointment. Thus, in January 2020, the Army Act, 1952 was amended by consensus, factoring in age related extensions in the tenure of Service Chiefs, Chairman and Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee (CJCSC).

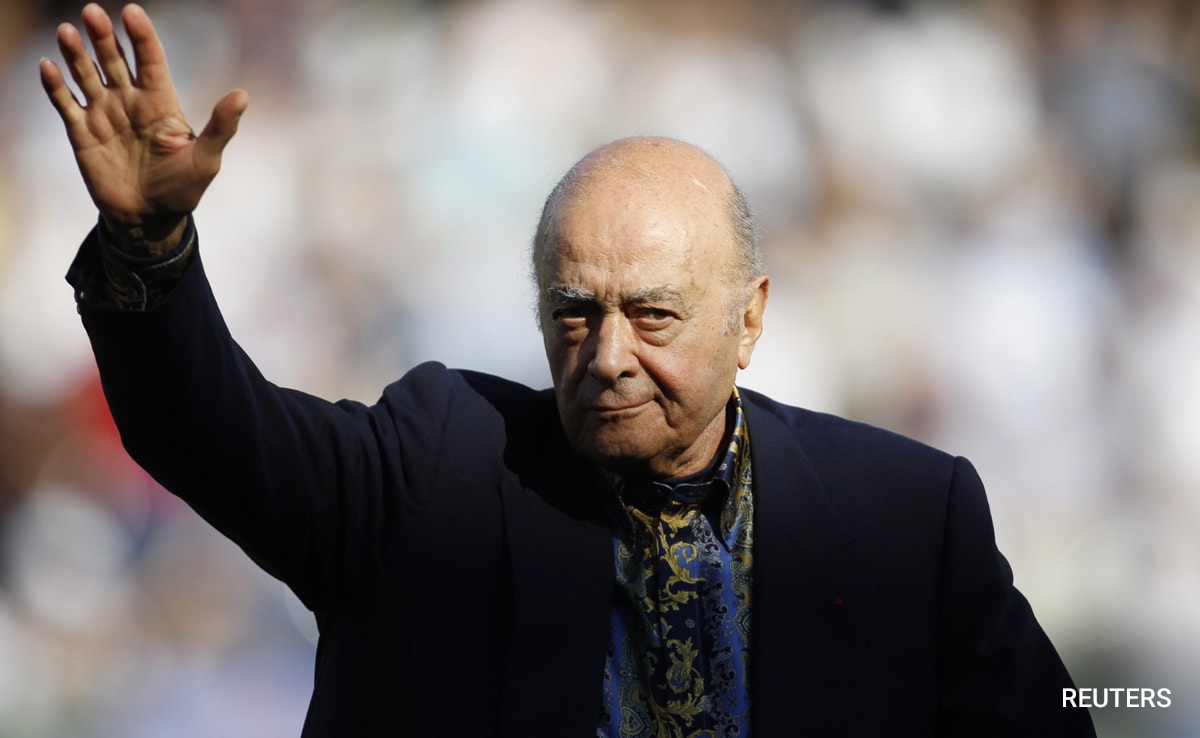

The reign of CJ Bandial

Mr. Bandial’s tenure was plagued by the selective assignment of judges to benches and the isolating of two senior most judges, Justices Qazi Faez Isa and Tariq Masood from case work, while Justices Ijazul Ahsan and Munib Akhtar were overtly favoured and assisted him in politically sensitive cases. The Bandial Court was publicly perceived to be openly partial to ousted PM Imran Khan. All encompassing anticipatory bail was given in the plethora of cases filed against him. Even when Mr. Khan was arrested in May, and brought to court under the custody of a posse of Pakistan Rangers, CJ Bandial made sure that the former PM was quickly released on bail by a lower court. In the Toshakhana case, Mr. Bandial sought to intervene even as appeal proceedings were pending before the Islamabad High Court.

Furthermore, allegations on complicity in bench fixing and corruption among Supreme Court Judges emerged in audio leaks. Instead of recusing from the Bench, as audios of his mother-in-law were included, the CJ reserved judgment and sat over the case for three months before issuing a 32 page long-winded order, dismissing it as a challenge against judicial independence. The schisms within the current 15-member Court came out into the open, with judges on his own Bench questioning the power of the Chief Justice’s ‘one-man show’.

For example, new law was written into Article 63A of the 1973 Constitution, wherein votes cast under a whip by the parliamentary party leader were deemed valid, not that of the party’s head. This seemed contrary to the powers given under Article 95 for a ‘conscience’ vote during a no-confidence motion. This ruling enabled the ouster of the Pakistan Muslim League (N)’s Hamza Shehbaz-led provincial government in Punjab and its replacement by a pro-Imran dispensation under Chaudhry Pervaiz Elahi.

Similarly, when a Bench led by Qazi Faez Isa ruled in March, against the powers of the Supreme Court to initiate suo motoproceedings under Article 184 (2), CJ Bandial overruled this judgment. When the Shehbaz Sharif coalition government legislated later to amend these powers under the Supreme Court (Practice and Procedure) Bill, 2023, Mr. Bandial ruled the Act as `beyond the legislative competence of Parliament’.

The way forward

In the fractious backdrop of a burgeoning executive-judiciary conflict, the 64-year-old Qazi Faez Isa was designated Pakistan’s new Chief Justice in July, almost two months before Mr. Bandial’s retirement. Mr. Isa has had multiple run-ins with the federal, civilian and military establishment. In the Quetta Commission report (2016) constituted by the Supreme Court of Pakistan under Article 184(3) to investigate the August 8 terrorist attacks in Quetta, he commented adversely on ineptitude, particularly of the Interior Minister, Chaudhry Nisar Ali Khan.

After the Tehreek-e-Labaik Pakistan (TLP)’s sit-in demonstrations at Faizabad Mor paralysed public life, Justice Isa criticised, in February 2019, ‘excesses’ of the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), the Intelligence Bureau (IB) and the Military Intelligence (MI) in first fostering and later, dispersing the protestors. This led to the filing of a reference against him in the Supreme Judicial Council (SJC) by the Imran Khan government.

Surviving these obstacles in appearances before the SJC, and despite feet dragging by a reluctant Mr. Bandial after the People’s Democratic Movement (PDM) government withdrew the reference, Mr. Qazi Faez Isa has now taken over as CJ, albeit for a short, one year term (till October, 2024). He would have to focus on selecting one new judge to complete the 17-member court and address contentious judgments on constitutional and administrative powers.

Though there is a seeming constitutional impasse over fresh delimitation of constituencies after a new Census, Mr. Isa will have to take a call on the 90-day deadline for holding fresh elections, so that the caretaker government’s tenure does not get inordinately extended.

In sum, though interspersed with brief bouts of independence, Pakistan’s higher judiciary has fallen in line, whenever threatened by unforeseen outcomes of political engineering by the omnipotent military establishment. CJ Isa’s tenure at least holds the promise of a return to a more principled interpretation of basic law tenets, preserving the sanctity of Pakistan’s only consensus document, the 1973 Constitution.

The writer is former Special Secretary, Cabinet Secretariat.