Ghanas lead negotiator Sam Adu-Kumi speaks as Alejandra Parra, zero waste and plastics advisor for GAIA Latin America and the Caribbean, listens at a press conference during the fifth meeting of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee to develop an international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution (INC-5) in Busan on December 1, 2024.

| Photo Credit: AFP

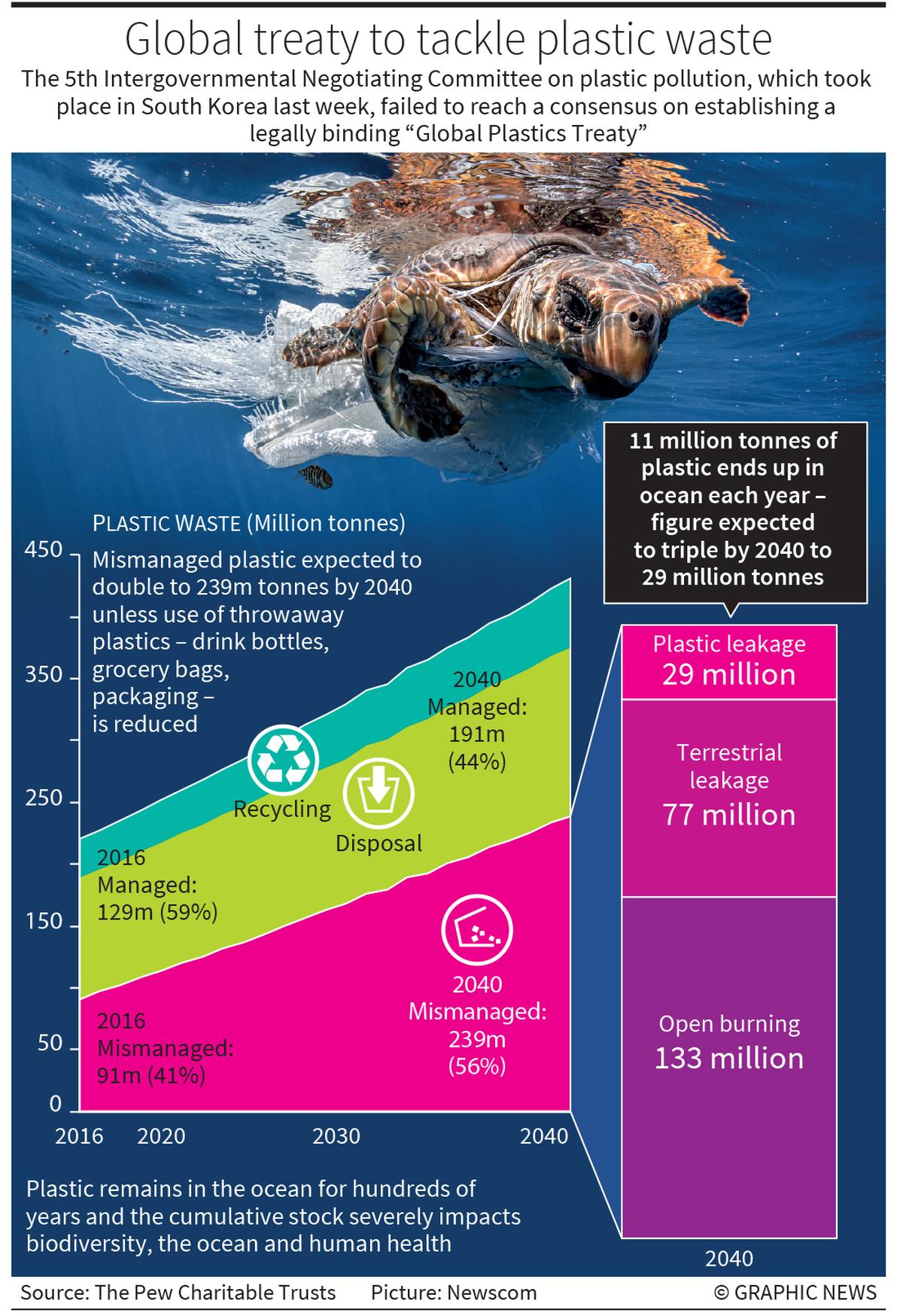

The story so far:The 5th Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC-5) on plastic pollution was a conclave of delegations from about 170 countries mandated to establish a legally binding treaty to end plastic pollution, informally called the Global Plastics Treaty. Despite a week of meetings, the INC-5 failed to meet its mandate.

What is the Global Plastics Treaty?

The United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA) resolved in March 2022 to ‘end plastic pollution, including in the marine environment.’ To that end, INC committees were constituted and tasked with negotiating a treaty before the end of 2024. Over the last two years, countries met five times, and attempted to bridge divergent views on how to end plastic pollution. Several countries are enthusiastic about ways and means to encourage recycling and prohibit certain plastics that lead to littering — India for instance has banned single-use plastic since 2022 — but many of them are reluctant to limit plastic production. Several countries are either petro-states or those that have significant industries that manufacture plastic polymers. Before the latest, and what was expected to be the last round of negotiations, began in Busan, South Korea, the Chair of the INC-5, Luis Vayas Valdivieso, circulated a draft text called a ‘non paper.’ This was roughly a synthesis of the views of all countries on managing plastic production but in the end, it turned out that despite long negotiations, the chasm between countries who viewed addressing plastic pollution as a waste management problem, and those that saw it as unachievable without cutting its production at source, was one that was too wide to bridge.

How bad is the problem of plastic pollution?

According to a United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) factsheet, plastic waste generation nearly trebled from between 1970 and 1990. In the early 2000s, the amount of plastic waste generated rose more in a single decade than it had in the previous 40 years. Currently, the world produces about 400 million tonnes of plastic waste every year. If historic growth trends continue, global production of primary plastic is forecasted to reach 1,100 million tonnes by 2050. There has also been a worrying shift towards single-use plastic products, items that are meant to be thrown away after a short use.

Approximately, 36% of all plastics produced are used in packaging, including single-use plastic products for food and beverage containers, of which 85% ends up in landfills or as unregulated waste. On top of that, about 98% of single-use plastic products are produced from fossil fuel, or “virgin” feedstock. The level of greenhouse gas emissions associated with the production, use and disposal of conventional fossil fuel-based plastics is forecast to grow to 19% of the global carbon budget by 2040. Of the seven billion tonnes of plastic waste generated globally so far, less than 10% has been recycled. Millions of tonnes of plastic waste are lost to the environment, or sometimes shipped thousands of kilometres to destinations where it is mostly burned or dumped. The estimated annual loss in the value of plastic packaging waste during sorting and processing alone is $80-$120 billion. Cigarette butts — whose filters contain tiny plastic fibres — are the most common type of plastic waste found in the environment. Food wrappers, plastic bottles, plastic bottle caps, plastic grocery bags, plastic straws, and stirrers are the next most common item.

What is India’s position on the treaty?

India said that it would be “unable” to support any measures to regulate the production of primary plastic polymers as it has larger implications in respect of the right to development of member States. Indian delegation leader, Naresh Pal Gangwar, of the Environment Ministry, said at the concluding plenary session India had always been “committed” to the principle of consensus in decision-making in respect of substantive matters under multilateral environmental agreements. This principle reiterated collective decision-making and reflects shared responsibilities and commitment. Elaborating on these points, India’s position was that it had banned 22 kinds of single-use plastic and put in place an Extended Producer Responsibility regime. This means that companies had to ensure a certain percentage of their plastic-packaging waste was recycled and that the littering of some of the most common kinds of plastic waste was banned. However, virgin polymer production is one of India’s major products and exports, with conglomerates such as Reliance having significant stakes in the industry. India viewed calls to cut plastic production and regulate its supply as akin to introducing barriers to trade. Its position was closer to that of China, Saudi Arabia and several other oil and petrochemical-refining states. At the talks, 85-100 of the gathered countries were supportive of cuts to plastic production, year-wise targets to achieve them and restrict supply and trade. Finally, India has strongly opposed proposals for countries to vote on propositions in draft texts that were produced at negotiations such as INC. In INC-like negotiations — like the Conference of Parties talks in climate — every single word and punctuation has to be agreed upon by all countries. This inevitably leads to deadlock that can take years to resolve. There have been proposals to include voting rights to engineer progress but countries have opposed this, on the ground that it violates the principle of equity.

Is this the end of the road?

By no means. It is expected that an “INC 5.2” will likely be convened sometime later next year to resume conversation and find common ground to firm a treaty. The final treaty, if agreed to, will lead to the beginning of a periodic Conference of Parties (COP) — just like in the climate talks. The UN talks in Rio de Janerio, in 1992, was where countries decided to address carbon dioxide emissions. It took three years until the first COP was organised in Berlin and in the 29 years since, the world has moved at a glacial pace to address CO2 emissions.

According to an analysis by the Center for International Environmental Law, multilateral environmental agreements have taken varying amounts of time to negotiate treaty text due to a range of factors, ranging from just over a year to nearly five years between the start of negotiations and treaty adoption. In addition, depending on the number of countries required to ratify, it is not unusual for several years to pass between adopting the treaty and its entry into force. For example, the Intergovernmental Conference on an international legally-binding instrument under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) for the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction held five sessions over five years. It met seven times by holding a “resumed” fifth session and a “further resumed” fifth session.

Published – December 08, 2024 02:21 am IST