In November, a Cabinet Minister reportedly stated at a press conference that the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) should focus on growth and not be concerned with food price inflation. Though the Minister clarified that he was speaking in his personal capacity, it is not in the spirit of things that once the central bank has been given a mandate to target an inflation index that includes the price of food, a member of the executive advises it in any way, leave alone exhorts it to target something else. The comment perhaps reflects some nervousness, on behalf of the government, about the performance of the economy. This would not be unfounded. The media has made references to declining consumption expenditure in the economy, though it is not evident in the national income statistics, available up to 2022-23. But there have been reports of the slow growth of sales of companies in the fast-moving-consumer-goods (FMCG) segment during the current financial year. This is a fairly reliable source of information on consumption growth. There is, however, a more overarching reason why the government would be concerned about growth in the economy, which is based on a longer view.

Not a comforting story

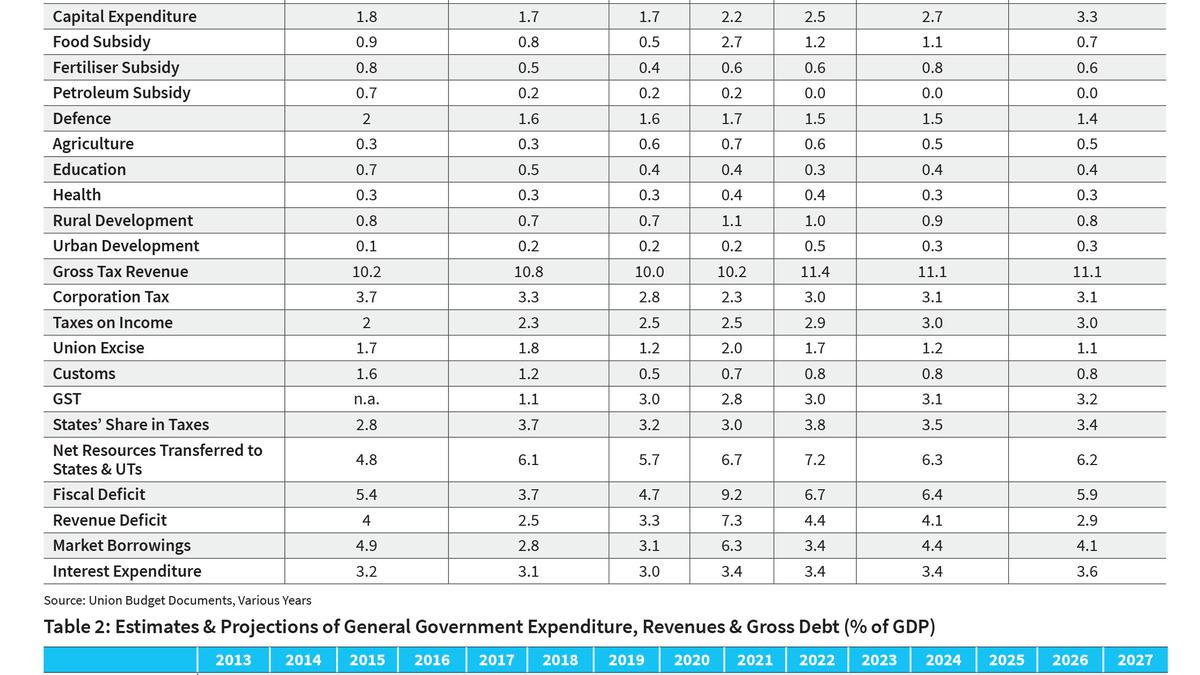

We now have national income data for a decade since 2014, enabling a broad evaluation of economic performance during the tenure of the Modi government. First, at the aggregate level, the average annual growth of the economy is lower since 2016-17. The decline is substantial too. At 7.1% for the period 2004-05 to 2015-16 and 5.2% for the period 2016-17 to 2023-24, it amounts to 27%. National income data for the sectors is less up to date but extends enough to make a confident assessment, and it would be as follows. Of the 11 sectors at the initial level of disaggregation, only one, namely ‘Real Estate’, shows a higher growth rate since 2014. Interestingly, for all of the policy focus on manufacturing, this sector actually slowed after 2014. Having grown at well over 7% per annum from 2006-07 to 2014-15, its growth slowed to just over 5% afterwards. This extent of decline in the rate of growth of manufacturing across successive growth phases is by far the highest since Independence while the percentage increase in the rate of growth of the real estate sector since 2014 is not the highest, having been exceeded in the 1980s. This would not be a comforting story for any government that takes pride in its growth performance.

While the government is vocal on growth, it remains silent on inflation. This is telling, as the October print for inflation shows that it breached the 6% mark, the upper tolerance level granted to the RBI, while food-price inflation breached the 10% mark. There is an assumption, commonly held by a section of the economics profession that was voiced by the Minister when he encouraged the RBI to ignore food price inflation. It is that the price of food is volatile, and its fluctuations cancel themselves out over time.

A structural problem

This, however, has been proven to be wrong, at least in India. Food inflation rose in 2019-20 and has remained elevated since. That it rose before the COVID-19 pandemic and has persisted even as growth has recovered gives us an idea of why the assumption is wrong. Recent inflation in India is not related to some temporary supply-chain disruptions, as, for instance, in the United States, where it has declined considerably post pandemic even as growth has recovered. Inflation in India is a structural problem reflecting the type of growth it is experiencing, one in which agricultural production is not expanding at the rate at which the demand for its products is rising. Further, and relevant in the context, food price inflation triggers a wage price spiral in the rest of the economy, which can continue for a while even if food prices decline.

The implication for welfare of the inflation we are currently experiencing is obvious. High inflation, especially of food products, adversely affects the well-being of those whose income does not keep pace with the inflation. The growth impact is less obvious, but surely is there. As household budgets are stretched to accommodate the higher cost of food, the demand for other goods and services must grow less fast. Non-agricultural output and employment growth now slows down. A mechanism of this kind is likely to have played a role in lowering the rate of growth of manufacturing production in recent years. From the data in the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation’s ‘National Accounts Statistics 2024’, we can see a correlation between the rise in food price inflation from 2019-20 onwards and manufacturing growth since, with the annual rate of change of the latter actually negative in two out of the five years since. So, while the Minister is right to suggest that the RBI’s capacity to rein in food inflation is weak, he is wrong to suggest that food price inflation need not be controlled. If food price inflation were to be taken out of the RBI’s brief without an alternative proposal for its control, India would be left bereft of an anti-inflation policy. Uncontrolled inflation can throw sand in the wheels of growth itself.

Presently, the problem facing India’s economy is not the lack of growth. The provisional estimate for GDP growth in 2023-24 (over 8%) is quite high by historical standards. The problem lies in its inequitable distribution across the population, partly induced by food price inflation. The Minister’s observation should induce the government to re-focus current economic policy from growth to inflation.

Pulapre Balakrishnan, Honorary Visiting Professor, Centre for Development Studies, Thiruvananthapuram

Published – December 25, 2024 03:12 am IST