Global Nutrition Targets (GNTs) were set by the World Health Assembly as key national indicators of the effect of public health policies in alleviating maternal and child malnutrition. Some of the targets were — reduce stunting by 40% in under-5 children, reduce anaemia by 50% in women of reproductive age, and no increase in childhood overweight.

A recent evaluation of the global progress toward the achievement (or not) of the targets was published in The Lancet. This colossal analysis provided estimates of progress at a regional and national level in 204 countries from 2012 to 2021, with projections up to 2050. In general, there appeared to be slow and insufficient progress across countries. By 2030, it was projected that few countries (not India) would meet the targets for stunting, and none would meet low birthweight, anaemia, and childhood overweight. In short, little progress in undernutrition, but an increase in overweight.

We are now in the last year of the first quarter of the 21st century. Fresh thinking is needed if the same sorry situation is to be avoided at the end of the next quarter of this century. The immediate questions are: why is there slow progress, and what next?

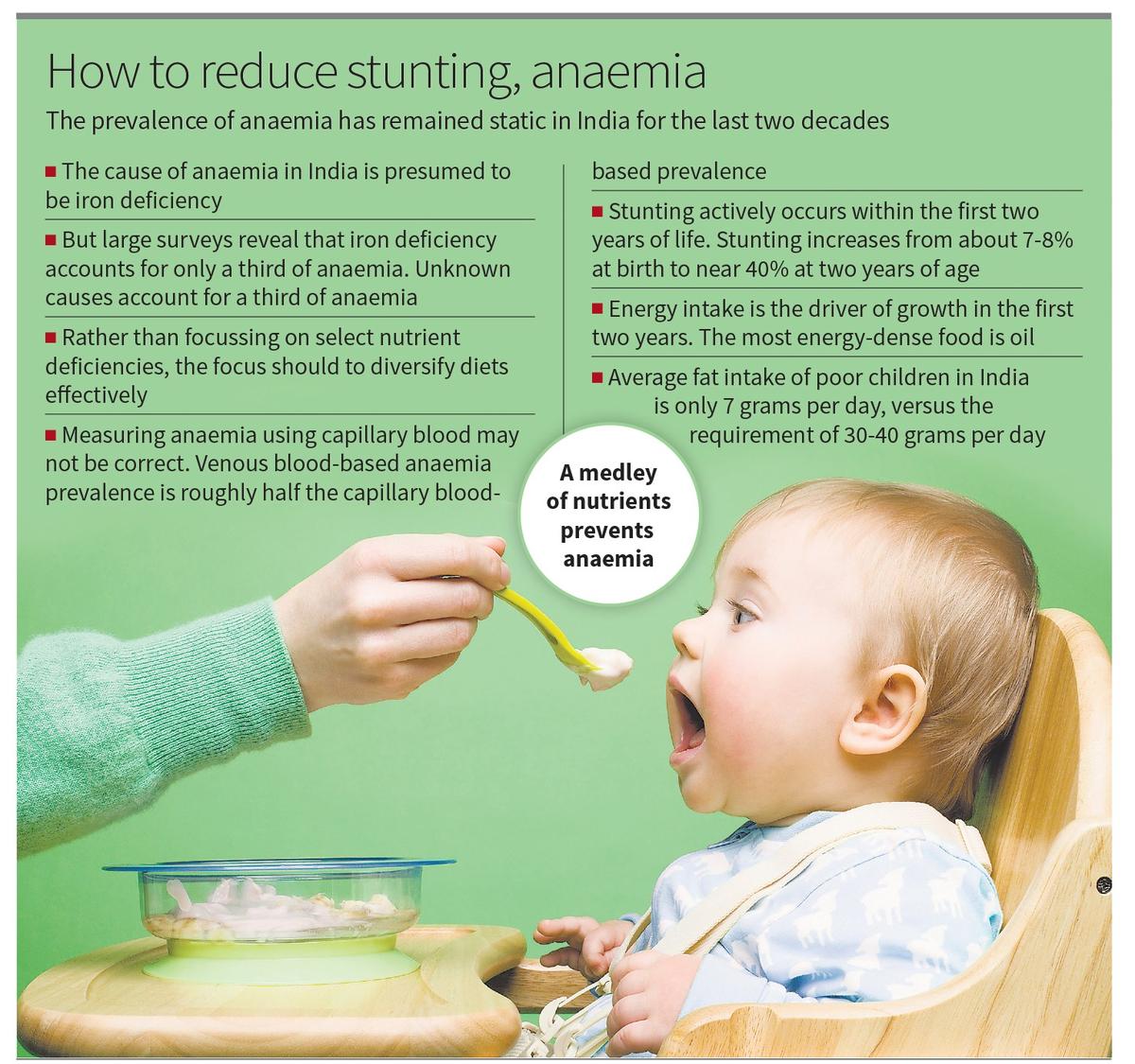

Slow progress can be blamed on poor programme implementation. However, other important aspects merit consideration too. For instance, the prevalence of anaemia has remained static in India for the last two decades. First, with no national surveys, we do not know the cause of anaemia in India. This is presumed to be iron deficiency, resulting in policies to improve dietary iron intake through fortification and supplementation. But recent large-scale surveys reveal that iron deficiency accounts for only a third of anaemia, while unknown causes account for another significant third. Tellingly, a study in north Karnataka school children during the COVID lockdown documented an increase in anaemia when the midday school meal was stopped, but this was not due to iron deficiency. Clearly, a medley of nutrients prevents anaemia, and the whole diet works better than the sum of its parts. Therefore, rather than focusing on select nutrient deficiencies, it is time to diversify diets effectively.

Second, the static anaemia prevalence, despite adaptation and chemical nutrient intake, begs the question of the metrics of measurement, which vary by context and method. In India, a national survey in children showed that venous blood-based anaemia prevalence (as recommended by WHO) was roughly half the capillary blood-based prevalence in comparable national surveys. Third, the actual diagnostic cut-off for anaemia (true for stunting as well) is the subject of much science: one cut-off might not fit all populations. Accurate metrics are crucial for successful public health interventions.

As for the sustained negligible progress in the target for stunting, the knee-jerk response might be to feed even more. But this has unintended consequences — children are more likely to grow fatter rather than faster when overfed after two years of age. This is because stunting actively occurs within the first two years of life; in India, stunting increases from about 7-8% at birth to nearly 40% at two years of age. On average, children reach half their adult height in two years. If already stunted at two, it is difficult to un-stunt children by overfeeding in the hope of faster growth. Prevention in the first two years is most important, even though the global nutrition target refers to stunting in under-5 children.

Second, energy intake is the driver of growth in the first two years. The most energy-dense food is oil. It is disheartening that the average fat intake of poor children in India is just 7 grams per day (NNMB reports), versus their requirement of 30-40 grams per day. But it is encouraging to note that the new POSHAN guidelines for feeding children aged under-3 with take-home rations now include oil, which was not specified earlier.

Finally, The Lancet paper showed that overweight had increased in children in almost all countries but was less than the prevailing undernutrition. This might mean that policy should continue to focus on undernutrition. But overweight does not capture the risk of ‘metabolic overnutrition’ in children. It has been shown that metabolic risk occurs in about no less than 50% of Indian children aged 5-19 years, even in those stunted and underweight. Therefore, the burden of childhood overnutrition should be an important policy target.

The slow progress in GNTs on undernutrition, notwithstanding the considerations pointed out above and the hidden overweight burden, tell us that the need of the hour is to zealously and precisely focus on double duty actions to simultaneously address the under- and over-nutrition burden. Else, ongoing efforts that are skewed towards undernutrition will continue to fuel overnutrition and related non-communicable diseases.

(Anura Kurpad is Professor of physiology and nutrition at St John’s Medical College, Bengaluru. Harshpal Singh Sachdev is a senior consultant in paediatrics and clinical epidemiology, Sitaram Bhartia Institute of Science and Research, New Delhi)

Published – January 04, 2025 10:00 pm IST