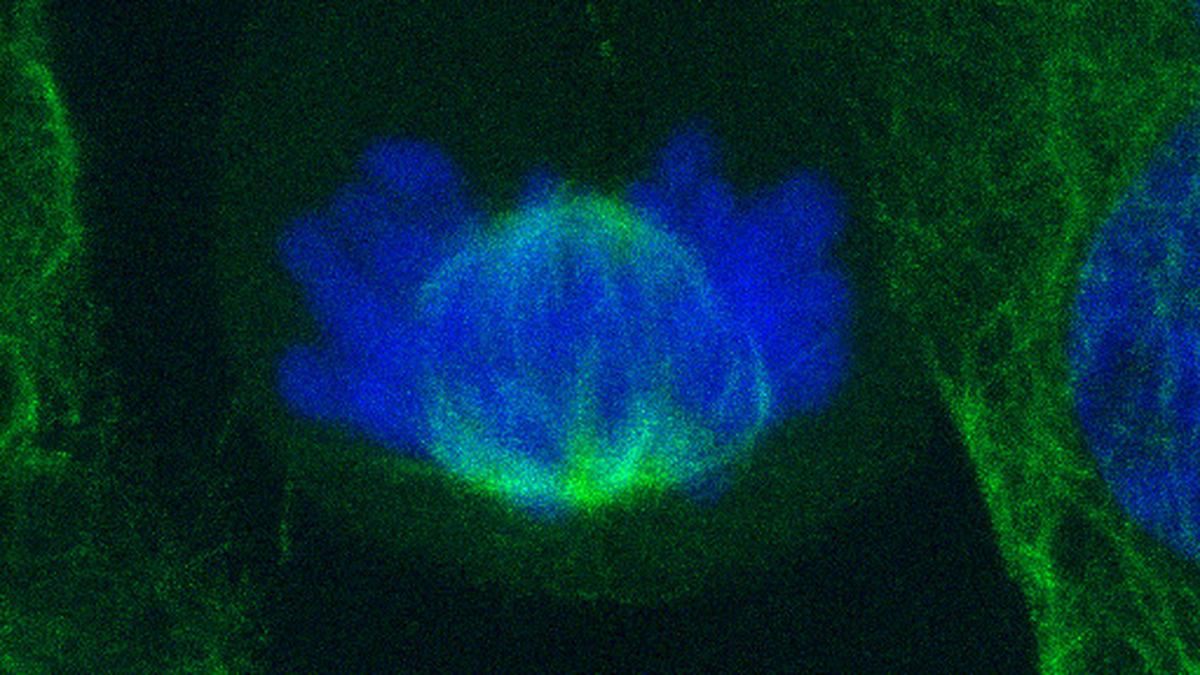

India has completed and made available a year-long compilation of 10,000 human genomes from India, representing 83 population groups, or about 2% of the country’s 4,600 population groups as a database. This collection will serve a template of future investigations into disease and drug therapy.

This ‘Genome India’ database, as it is known, will now be available to researchers across the world for investigations and is housed at the Indian Biological Data Centre (IBDC), in Faridabad, Haryana.

A first analysis of the genomes estimates around 27 million low-frequency (or relatively rare) variants, with 7 million of them not found in similar reference databases around the world. Certain population groups show higher frequencies of alleles, or different versions of the same gene. Over the last two decades, many countries have created databases of the genomes of their population — for a variety of purposes including estimating disease risks, adverse drug reactions, establishing genealogy and DNA-profiling databases.

However, a major focus of the Indian reference genomes is to have researchers study diseases. “The discoveries from Genome India are not just scientific — they hold the potential for targeted clinical interventions, advancing precision medicine for better healthcare,” said Union Minister of State (independent charge) for Science and Technology Jitendra Singh, at an event here to announce the project.

Researchers wishing to access the genomes must send in a proposal that will be perused by an independent committee with a commitment that will adhere to data sharing and privacy policies. Though the database stores information on population groups, this data will not be classified by the names of castes or tribes but will be numerically coded, Rajesh Gokhale, Secretary, Department of Biotechnology told The Hindu.

Describing the project as “historic”, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, in a video address, said this paved the way for India strengthening the biotechnology economy as well as biotechnology-based manufacturing.

Experts associated with the project said that while only a small fraction of India’s population groups were studied, the door was open to expanding the database to a million genomes. “Though costs are a limiting factor, a million would dramatically scale insight into India’s genetic diversity,” said Kumaraswamy Thangaraj of the Centre for Cellular Microbiology, Hyderabad and one of the leaders of the project.

Published – January 10, 2025 02:54 am IST