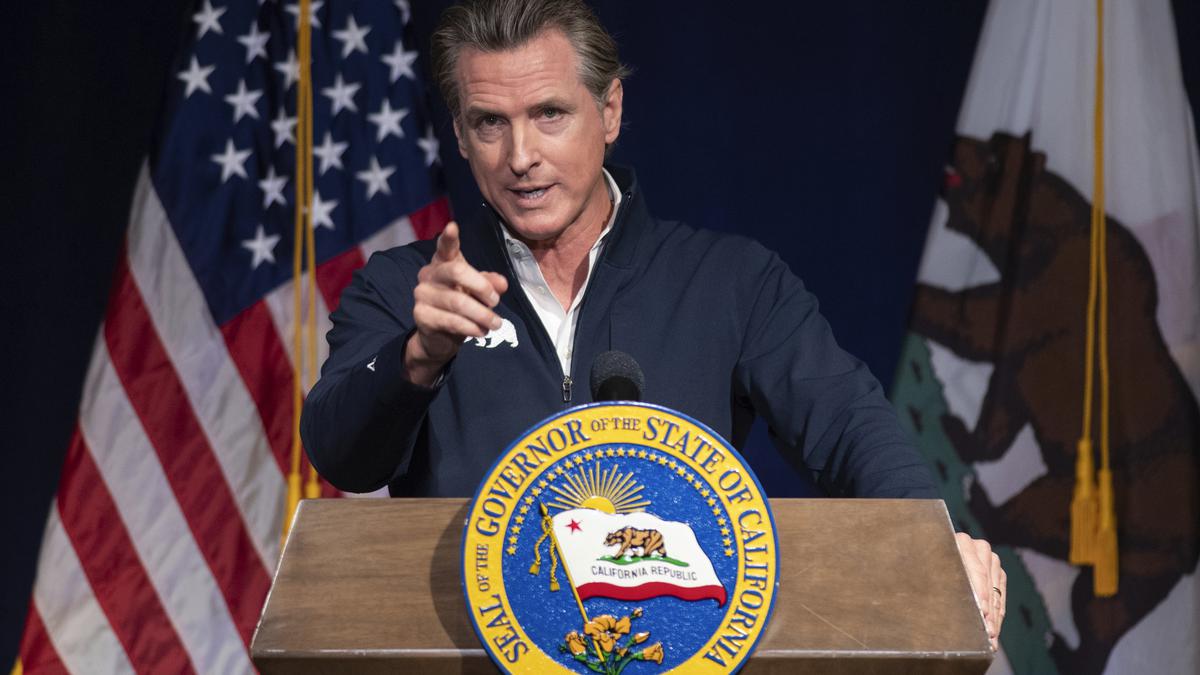

Gov. Gavin Newsom vetoed a bill on October 7 that would have made California the first U.S. state to outlaw caste-based discrimination.

Caste is a division of people related to birth or descent. Those at the lowest strata of the caste system, known as Dalits, have been pushing for legal protections in California and beyond. They say it is necessary to protect them from bias in housing, education and in the tech sector — where they hold key roles.

Earlier this year, Seattle became the first U.S. city to add caste to its anti-discrimination laws. On Sept. 28, Fresno became the second U.S. city and the first in California to prohibit discrimination based on caste by adding caste and indigeneity to its municipal code.

Also read: Explained | Will the Seattle move shield against caste bias?

In his message Mr. Newsom called the bill “unnecessary,” explaining that California “already prohibits discrimination based on sex, race, color, religion, ancestry, national origin, disability, gender identity, sexual orientation, and other characteristics, and State law specifies that these civil rights protections shall be liberally construed.”

“Because discrimination based on caste is already prohibited under these existing categories, this bill is unnecessary,” he said in the statement.

A United Nations report in 2016 said at least 250 million people worldwide still face caste discrimination in Asia, Africa, the Middle East and Pacific regions, as well as in various diaspora communities. Caste systems are found among Buddhists, Christians, Hindus, Jains, Muslims and Sikhs.

Proponents of the bill launched a hunger strike in early September pushing for the law’s passage. During their campaign, many Californians have come forward with stories of discrimination in the workplace, housing and education. Opponents, including some Hindu groups, called the proposed legislation “unconstitutional” and have said it would unfairly target Hindus and people of Indian descent. The issue caused deep divisions in the Indian American community. Hundreds on both sides came to Sacramento to testify at committee hearings in the state senate and assembly.

Thenmozhi Soundararajan, executive director of Equality Labs, the Oakland-based Dalit rights group that has been leading the movement to end caste discrimination nationwide, said she still views this moment as a victory for caste-oppressed people who have “organized and built amazing power and awareness on this issue.”

“We made history conducting the first advocacy days, caravans, and hunger strike for caste equity,” she said. “We made the world aware that caste exists in the U.S. and our people need a remedy from this violence. A testament to our organizing is in Mr. Newsom’s veto where he acknowledges that caste is currently covered. So while we wipe our tears and grieve, know that we are not defeated.”

The Hindu American Foundation and Coalition of Hindus of North America claimed Newsom’s veto as a victory for their advocacy efforts.

“With the stroke of his pen, Governor Newsom has averted a civil rights and constitutional disaster that would have put a target on hundreds of thousands of Californians simply because of their ethnicity or their religious identity, as well as create a slippery slope of facially discriminatory laws,” said Samir Kalra, the Hindu American Foundation’s managing director.

In March, State Sen. Aisha Wahab, the first Muslim and Afghan American elected to the California Legislature, introduced the bill. The California law would have included caste as a sub-category under ethnicity — a protected category under the State’s anti-discrimination laws.

Nirmal Singh, a Bakersfield resident and member of Californians for Caste Equity, said the introduction of this bill “represents a shifting tide in California to understand caste-based discrimination.” Singh also represents Ravidassia community, many of whom are Dalits with roots in Punjab, India.

“The fact that caste-oppressed people were given a platform to stand up for our basic human rights is a huge win in and of itself,” he said.

Earlier this week, Republican state Sens. Brian Jones and Shannon Grove called on Mr. Newsom to veto the bill, which they said will “not only target and racially profile South Asian Californians, but will put other California residents and businesses at risk and jeopardize our state’s innovate edge.”

Mr. Jones said he has received numerous calls from Californians in opposition.

“We don’t have a caste system in America or California, so why would we reference it in law, especially if caste and ancestry are already illegal,” he said in a statement.

Grove said the law could potentially open up businesses to unnecessary or frivolous lawsuits.

A 2016 Equality Labs survey of 1,500 South Asians in the U.S. showed 67% of Dalits who responded reported being treated unfairly because of their caste.

A 2020 survey of Indian Americans by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace found caste discrimination was reported by 5% of survey respondents. While 53% of foreign-born Hindu Indian Americans said they affiliate with a caste group, only 34% of U.S.-born Hindu Indian Americans said they do the same.