Last month, Meena Bishnoi bought an acre on the Moon. It wasn’t the thrill of buying land in space that drove her though; the nursing officer at AIIMS Jodhpur had something more significant in mind.

In early August, the 30-year-old was discussing Chandrayaan-3’s prospective landing with a friend in Ireland, when the friend suggested gifting her some land on the Moon. The two had been interested in space since their childhood, but being girls in Rajasthan meant they couldn’t pursue their interest. Bishnoi didn’t want the same happening to her pre-school daughters, Meghna and Laxita.

As with any new place in human history, the scramble to ‘colonise’ the Moon has begun.

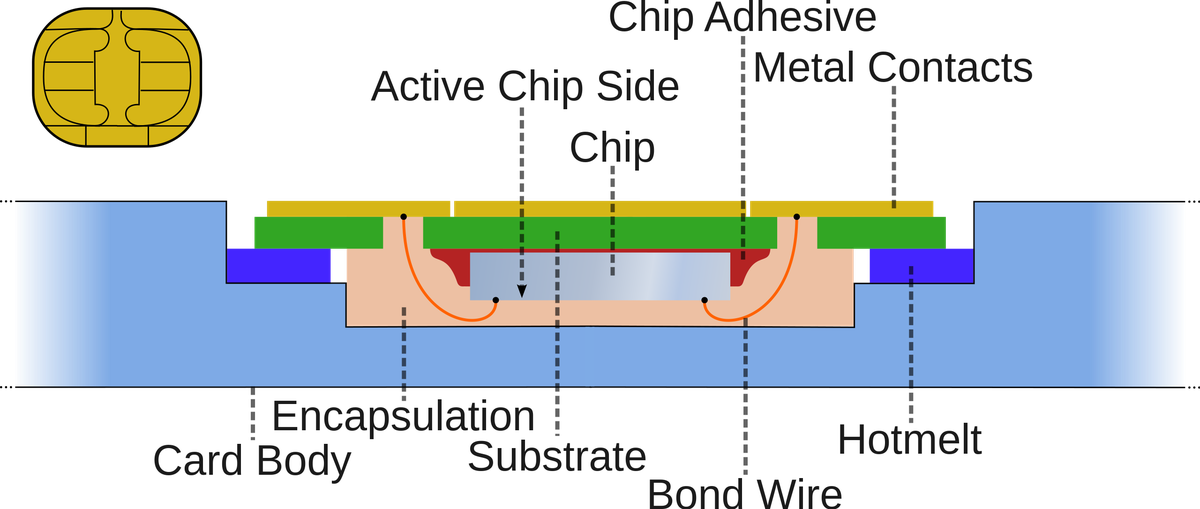

| Photo Credit:

Illustration: Sumit Kumar; colours by Tushar Attri

“I’ve always been very sensitive about the issue of the girl child,” says Bishnoi, who was married off when she was in Class XII. It was only thanks to a progressive grandfather-in-law, an advocate, that she was allowed to go back to school. “I see my two daughters as my chaand ke tukde. So, I wanted to give them a piece of the Moon — to show them what they mean to me, and that they can reach the Moon if they wanted to.”

On August 19, the two friends bought an acre in the ‘Lake of Happiness’, which is located centrally on the visible side of the Moon, from the Lunar Society of India (lunarregistry.com).

Meena Bishnoi

A lunar homestead

As the race to space bristles with new entrants, talk of human life beyond Earth, once unfathomable, is not uncommon. With companies such as Elon Musk’s SpaceX, Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic and Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin pioneering space tourism, and most recently, India’s Chandrayaan-3 lander touching down on the far side of the Moon, the lunar surface seems closer than it has ever been. And as with any new place in human history, the scramble to ‘colonise’ it has begun.

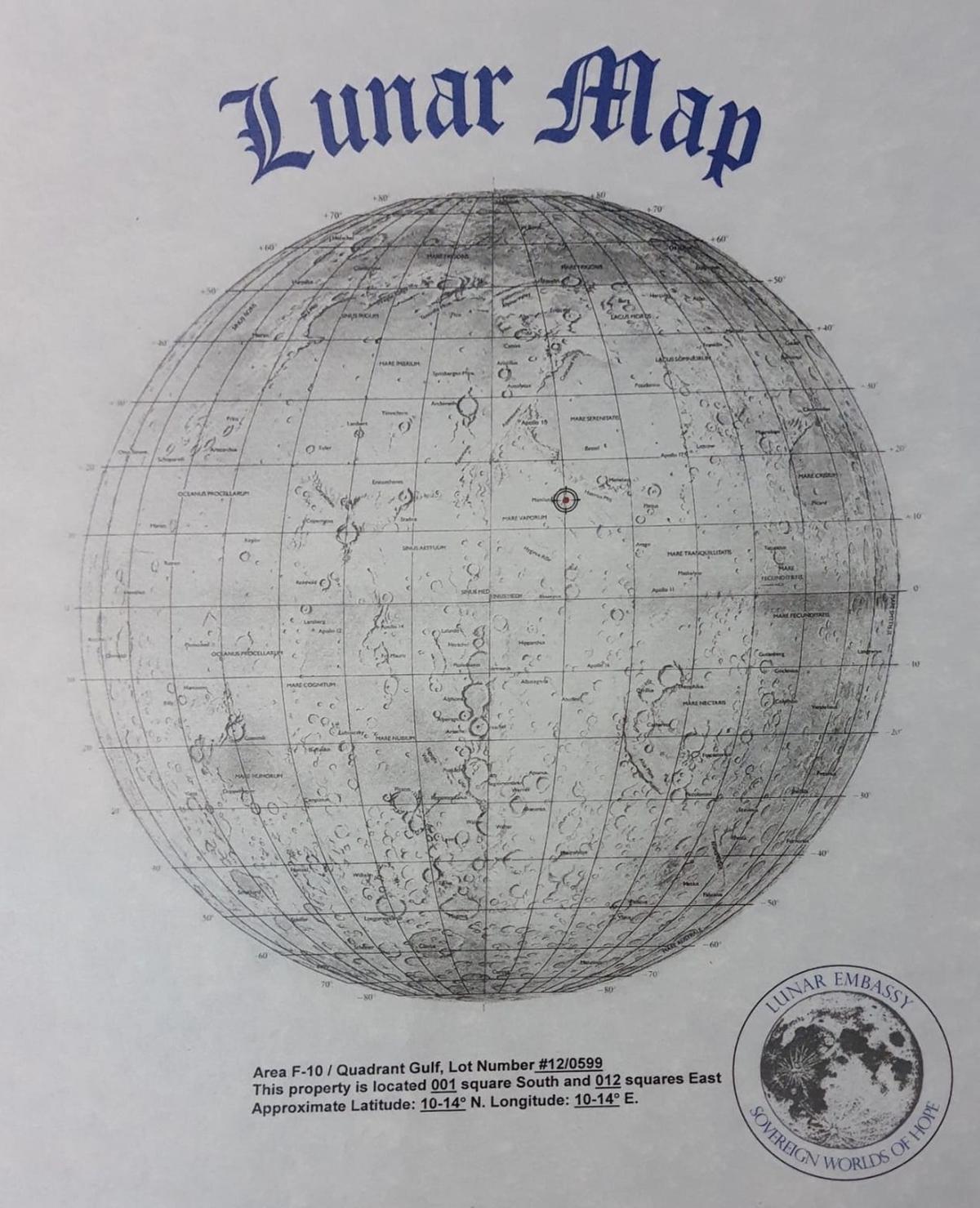

A cursory Google search is sufficient to see the motley group of organisations and websites selling land on the Moon. With names such as Lunar Embassy, Cosmic Register and Moon Estates, most of them are based abroad and offer buyers an acre for as little as $34.99 (approx. ₹2,890). The purchase often comes with a certificate of the land claim, a satellite image of the land, and mineral rights for a depth of five kilometres below the surface. It seems an affordable, if rather unbelievable, bargain. And it hasn’t cropped up under a ‘10 best cons of the century’ headline, yet.

But it begs the question, can one really buy lunar property? The rules surrounding ownership of the Moon and other bodies in outer space were laid down more than 50 years ago, with the U.N.’s Outer Space Treaty of 1967. It clearly states that outer space is “the province of all of mankind” and no country can appropriate it for its own purposes. Signed by 109 nations to date, including the U.S. and India, the treaty is often considered the Magna Carta of space legislation, and effectively bars private ownership in space. That hasn’t stopped people from trying though.

“People are taking advantage of the fact that the jurisprudence of international space law is relatively under-evolved, and using this to sell things like land on the Moon. But you can’t sell something you don’t own; neither can you sell something that nobody owns.”Ashok G.V.Lawyer who specialising in space law

One famous instance was in 1996, when a German citizen named Martin Juergens declared that the Moon belonged to his family. He stated that the Prussian king Frederick II had gifted it to his ancestors in 1756; the German government ignored him.

Over a decade earlier, in 1980, U.S. citizen Dennis Hope went to his local county registrar’s office in Contra Costa County, a suburb of San Francisco, and filed a notice of his claim of ownership over the Moon, eight other planets in the solar system and their moons. He followed this up with letters to the U.S. government, the then Soviet government and the U.N., informing them of his claim (he received no response). That same year, he set up his company, Lunar Embassy, to subdivide and sell land on the Moon. The company exists till date, its website claiming it has sold more than 611 million acres, including to three former U.S. presidents: George H.W. Bush, Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan.

Dennis Hope who claimed of ownership over the Moon, eight other planets in the solar system and their moons

“My father realised there is a loophole in the Outer Space Treaty,” says Christopher Lamar, Hope’s son and current CEO of Lunar Embassy. “It talks about how governments cannot own celestial bodies, but it makes no mention of individuals.” Hope combined this loophole with an old law he had read about in history class, the Homestead Act of 1862 — whereby pioneers who settled in the U.S. used a claimant system. “They would say, ‘The land from that tree to that rock is mine,’ effectively laying claim over it. And my father found that most developed countries in the world had similar systems for expanding populations. So, he saw that as global precedent, and used it to lay claim to the Moon,” adds Lamar.

Christopher Lamar

Their profile of buyers, the website claims, comprises everyone from celebrities and corporations, to blue collar workers. With most of their demand coming from North and South America, India and Japan, this year India is in second place (after the U.S.) for total number of buyers.

Padding up the sales pitch is Lamar’s claim that their underlying motivation is not profit, but something more democratic. “The Outer Space Treaty says that the Moon should be used for the benefit of all humanity,” he says. “The more landowners, the stronger our voice, and we can raise it against big-money’s appropriation of the Moon.” He plans to charge corporations licensing fees as high as $100,000 to access parts of the Moon.

Everyone wants in

Last month, “extremely high order volume following the successful landing of Chandrayaan-3” had the Lunar Registry state that their website was “experiencing lengthy processing and fulfilment delays”. Meanwhile, many other Indians kept their wallets sealed and merely named their newborns Vikram and Pragyan.

A mistake? It doesn’t matter

The Lunar Embassy has ambassadors in countries such as Japan and South Korea who sell land; they also have an ‘unofficial’ arrangement in India, whereby someone buys land from them and resells it. “We often face issues with payments from India — Paypal doesn’t work, Venmo is not successful. So, we needed someone in the country to help us out,” says Lamar.

That’s where Rajat Rajan, 41, stepped in. Apart from running his own exporting business in Dehradun, he moonlights as the founder of Chaand Pe Zameen. His business model is simple: he buys land from the Lunar Embassy and sells it in India at a slight markup. He started in 2020 with 20 one-acre plots; within a year he sold all of them for ₹2,500 each. Recently, he bought six more acres and has already sold three.

“People often ask me, how can you sell the Moon? Sometimes they laugh at me, they think I’m a fraud,” he says, sharing how, when he tried to advertise in a local newspaper, it withdrew his advertisement stating it was not legally tenable. But none of this has deterred Rajan. In fact, he aspires to be like Dennis Hope, who “was first laughed at, but now has millions of customers”.

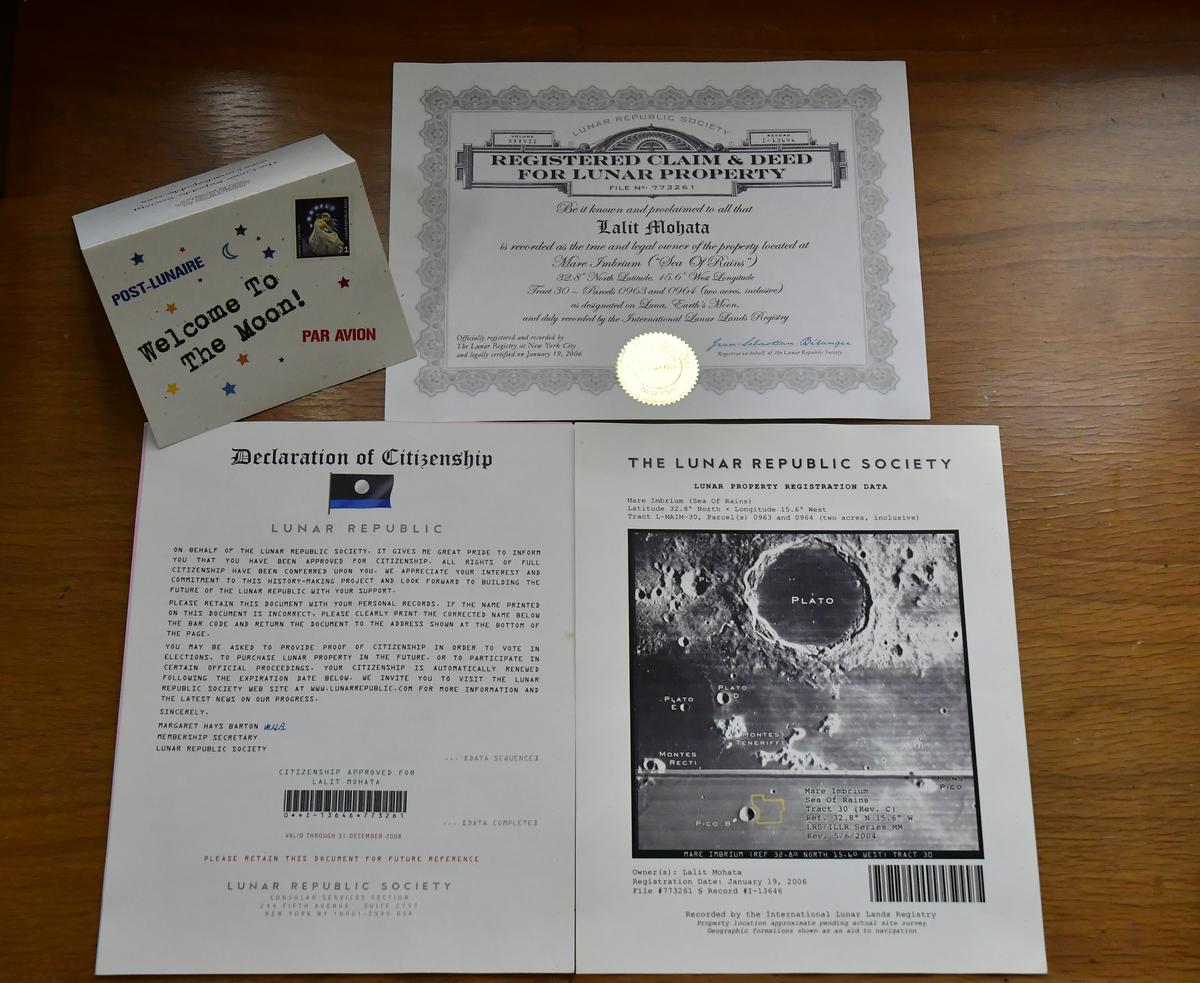

Documents of a two-acre plot on the Moon sent to Lalit Mohata

| Photo Credit:

K. Murali Kumar

Rajan, who has seen a spike in demand in the wake of the Chandrayaan-3 landing, says most of his buyers are middle-class and have never owned land before. Such as Mohima Chakraborty. Last year, the 24-year-old from Kolkata bought one acre as a gift for her husband Tanmoy on his 27th birthday. She got the idea when she read about the late actor Sushant Singh Rajput allegedly owning land on the Moon. Chakraborty reached out to the Lunar Embassy via email, who directed her to Rajan. “At first, I was confused about whether it is real or fake, but Rajan convinced me that no problems would occur,” she says.

Mohima Chakraborty with her husband Tanmoy

| Photo Credit:

Debasish Bhaduri

“When I gifted it to my husband, he was so overwhelmed. He went through all the documents with tears in his eyes. We come from a middle-class family, and never thought we’d be able to buy our own land. It was a dream come true for us.” For her next birthday, Mohima hopes her husband will gift her a star, or at least name one after her. (Another eyebrow-raising scheme, there are a few companies who provide this service. But global bodies such as the International Astronomical Union have refused to recognise such endeavours.)

One of the documents Chakraborty received

Indira Mohanta’s story is similar. A private school teacher in Krishnanagar, West Bengal, the 55-year-old heard of a man in nearby Ranaghat who bought land on the Moon last year. She jokingly told her daughter she would buy some too, though she wouldn’t be able to afford it. But when she reached out to the man and learned that it’s quite cheap, she bought two acres from Rajan in January, as a birthday gift for her daughter. “I know that in my lifetime I might never see this land, but I hope my grandchildren will someday,” she says.

Mohanta had her share of doubters, including her husband, who doesn’t believe the purchase is legitimate. She doesn’t discount their concerns, admitting that there’s a small chance that she has wasted her money. “But that’s okay. I waste my money on saris all the time. The important thing is, I’m happy with the purchase, and my daughter is happy with it. Till I’m alive, that’s enough.”

“The appeal of ownership is deep-rooted in the psyche of the Indian middle-class. There is a lot of inherited trauma and ideas of scarcity, right from the time of Partition. People lost their property, their lives were uprooted. There was so much uncertainty that the idea of owning land, or a piece of anything, is associated with prestige and belongingness. You couple that with the fact that today in India, owning land in, say, big cities is close to impossible. Unless it’s inherited, very few people can afford it.”Shevantika NandaNew Delhi-based psychologist

Outer space as investment

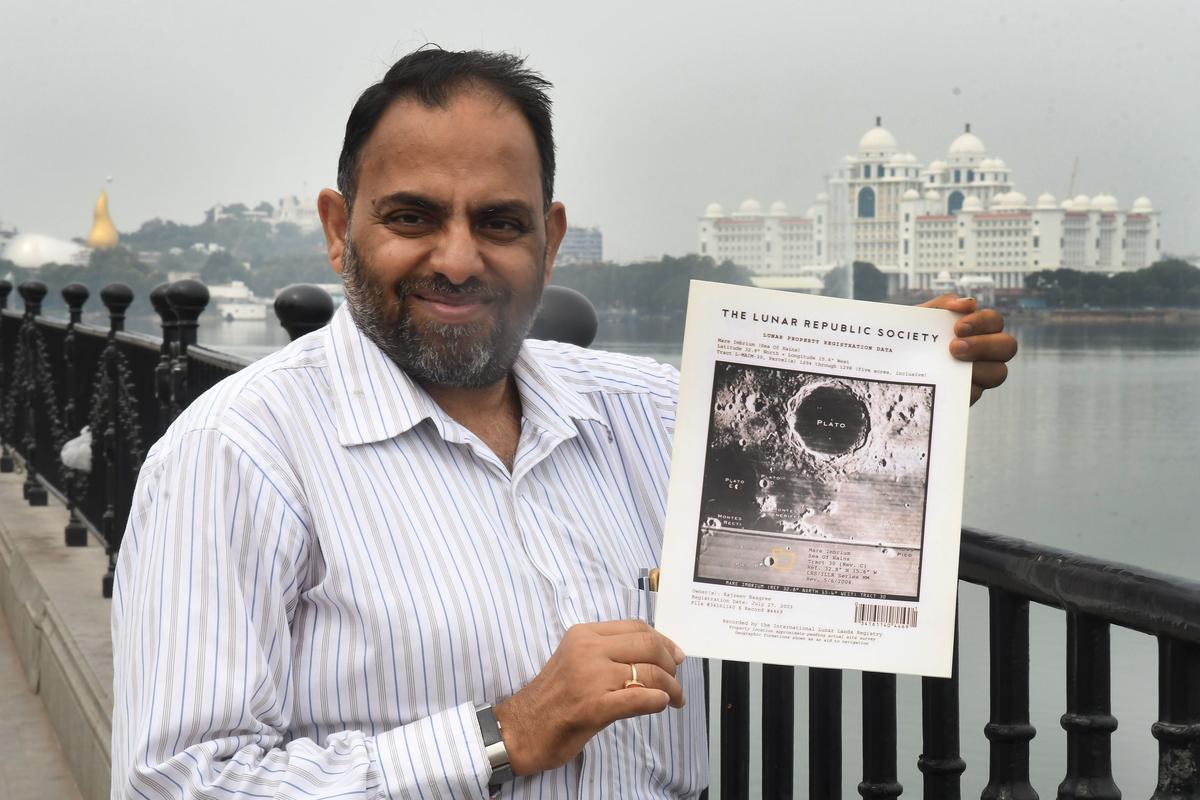

Apart from the novelty, there are some who consider it a legitimate investment. Cousins Rajeev B. (who prefers to go by Raajeevvv), 50, and Lalit Mohata, 46, invested in lunar land years ago, in 2003 and 2006, respectively.

A numerologist with eight copyrights to his name, Raajeevvv was one of the earliest ‘investors’. Though he was aware that the U.N. treaty prohibits countries from owning bodies in space, the Hyderabad resident also believed in the ‘purpose’ of organisations such as the Lunar Republic Society (lunarregistry.com), which sold people their own lunar land claims and used the proceedings for lunar exploration (how this is achieved on the basis of the paltry price tags attached to Moon acres — when annual investment in the space sector has gone up to $10 billion, according to a 2022 McKinsey report — has conveniently not been addressed). “When I bought the land, I knew I’d never go to the Moon,” says Raajeevvv. “But I bought it hoping the money would go towards space exploration and maybe one day, someone else will get to go.”

Raajeevvv B.

| Photo Credit:

G. Ramakrishna

An MBA in finance, Mohata’s salary in 2006 was a mere ₹10,000. But he broke a fixed deposit and invested ₹3,000 to buy two acres. Of his many investments since — including a flat in Bengaluru and 2,500 sq. ft. land in Bikaner — his lunar deal was the cheapest and the most exciting. “I invest with a vision that something will happen. Some visions are realised, and I’ll get a return on investment. Some are not, but that’s a risk I’m willing to take,” he says.

Lalit Mohata

| Photo Credit:

K. Murali Kumar

The question of ownership

So, is all this legal? “That’s a complicated question,” says Ashok G.V., 34, a Bengaluru-based lawyer who specialises in space law. “To my mind, the interpretation — that the Outer Space Treaty doesn’t stop private individuals from claiming land — is legally untenable. The treaty essentially deems space a global commons, and that rules out any private ownership of land,” says Ashok. “People are taking advantage of the fact that the jurisprudence of international space law is relatively under-evolved, and using this to sell things like land on the Moon. But you can’t sell something you don’t own; neither can you sell something that nobody owns.”

The last few years have seen legislation around ownership in space evolve, with countries such as the U.S. coming up with new iterations of the 1967 treaty. In 2020, the U.S. put forth the Artemis Accords, a non-binding arrangement between them and signatory countries, which sets down guidelines for behaviour in space. It also posits the creation of ‘heritage sites’ and ‘safety zones’ in designated areas of the Moon (for example, the site of the Apollo landings), which, according to critics, seems a first step towards countries starting to colonise different parts of the Moon.

Be like the native American

Prathima Muniyappa, 32, a space researcher at the MIT Media Lab in the U.S., surmises it is part of the larger “extractive mindset” that comes from the West. “When the British came to America to colonise it, they looked at the land and said, ‘Nobody owns this land. We arrived here first, so it is ours.’ And so, introduced western notions of property rights as an excuse to usurp the land. But the native Americans had a different conception of property. They believed in the right to the produce of the land: the right to hunt and fish. It’s a difference in attitude,” she says. If we as a species want to avoid making the same mistakes, we need to adopt a non-extractive mindset in our approach to space, starting with the realisation that space will always remain the common heritage of all humankind.

India itself doesn’t have any particular legislation around ownership in space. “But in case someone thinks they’ve been defrauded and wants to take legal action, there are provisions under the Consumer Protection Act, where you can say, ‘this was a misleading advertisement’,” says Deepika Jey, 36, a Madrid-based lawyer who also specialises in space law.

One can’t help wondering at what point the U.N. will step in and declare all purchases null and void. When that happens, will lunar landowners band together in protest or will it all shut down quickly, shrinking into an amusing anecdote? Only the next few decades will tell.

neha.vm@thehindu.co.in

Sumit Kumar is a cartoonist and founder of the comics and animation studio Bakarmax. He is the author of three graphic novels: The Itch You Can’t Scratch, Amar Bari Tomar Bari Naxalbari and Kashmir Ki Kahani.