The story so far: September 27 will mark the beginning of a historic legal battle in the climate action movement. The stage: European Court of Human Rights in France’s Strasbourg. The actors in question: 32 European governments (including the U.K., Russia and Turkey) and six young people from Portugal, aged 11 to 24. The plaintiffs are set to argue before 17 judges that their governments have failed to take sufficient action against the climate crisis, thus violating their human rights and discriminating against young people globally. Gearóid Ó Cuinn, of the Global Legal Action Network (GLAN), said the scale and consequence of the lawsuit are unprecedented. “This is truly a David and Goliath case…Never before have so many countries had to defend themselves in front of any court anywhere in the world,” he told reporters.

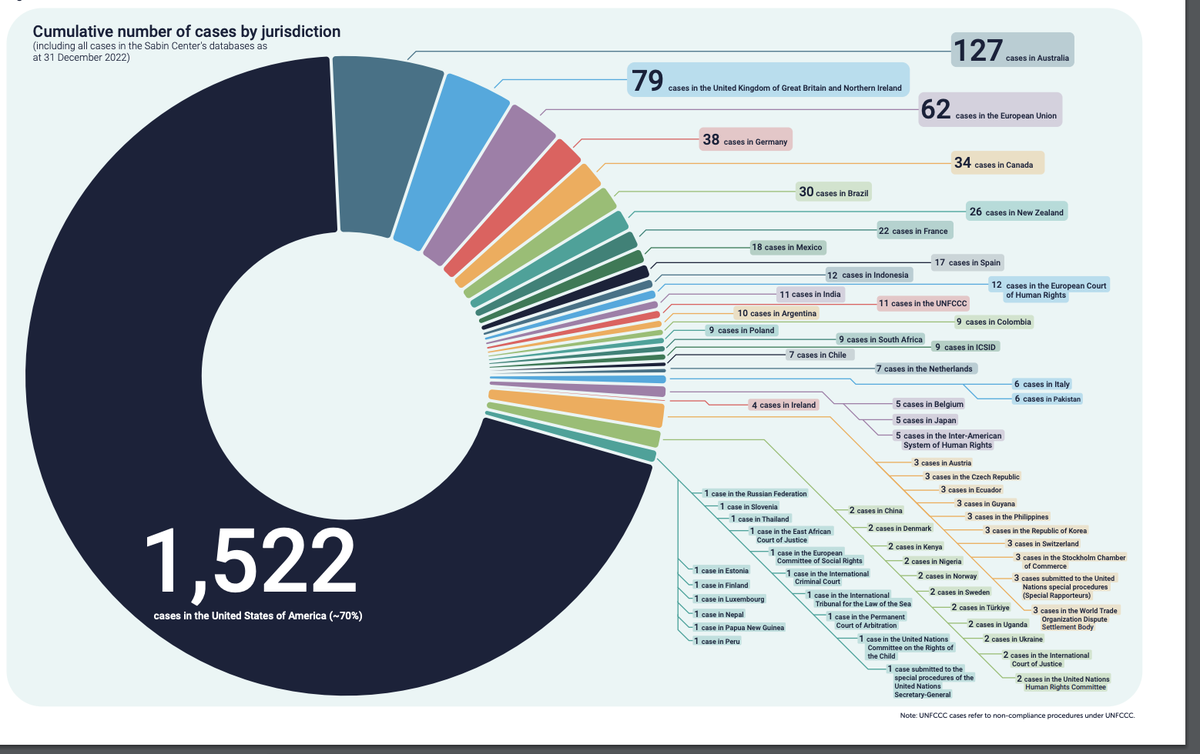

The narrative of young people taking governments to court is gaining momentum: as of December 2022, 2,180 climate-related cases were filed in 65 countries across international and regional courts, tribunals and quasi-judicial bodies, per the United Nations’s Global Climate Litigation Report. At least 34 cases were brought by, or on behalf of, children and young people under 25 years of age. Youth, in addition to women, local communities and indigenous stakeholders, were “driving climate change governance reform.”

What is the lawsuit?

Duarte Agostinho and Others v. Portugal and Others was filed in September 2020, in the aftermath of the wildfires that consumed Portugal’s Leiria in 2017. Almost 66 people died, and 20,000 hectares of forests were lost. The recent spate of heatwaves and fires across Greece, Canada and other parts of Europe served as reminders that every increment beyond the 1.5°C temperature threshold would be catastrophic, intensifying “multiple and concurrent hazards,” as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change states in its report.

The Portuguese youths claim that European nations have faltered in their climate emissions goals, blowing past their global carbon budgets consistent with the Paris Agreement target of limiting global warming under 1.5°C. They are expected to show scientific evidence that if every country moves at the current pace, global heating will rise to 3°C within their lifetime. The nations have thus violated people’s fundamental rights protected under the European Convention on Human Rights, including the right to life, the right to be free from inhuman or degrading treatment, the right to privacy and family life and the right to be free from discrimination. “

These European governments are failing to protect us… Our ability to do anything, to live our lives, is becoming restricted. The climate crisis is affecting our physical health and our mental health; how could you not be scared?” said André dos Santos Oliveira, 15, to a media house. More than 50% of young people, from France, India, and the U.S. among other countries, reported feeling sad, anxious, angry, powerless, helpless, and guilty as they have “little power to limit the harms of climate change”.

Since the 32 countries contributed to climate catastrophes and jeopardised the future of young people, it falls upon the nations to rapidly escalate their emissions reductions and aim higher in curtailing domestic emissions, in line with what scientific evidence shows, the lawsuit argues. Other suggested measures include cutting the production of fossil fuels and cleaning up global supply chains.

The European Scientific Advisory Board on Climate Change (ESABCC), a body which provides scientific advice to EU countries, said countries will have to target emissions reduction of 75% below 1990 levels (as opposed to the EU’s current 55%). “Under some of these principles, the EU has already exhausted its fair share of the global emissions budget,” their report states, echoing the plaintiffs’ claim that European countries have overstated their carbon budget claims. The EU at present is the sixth largest emitter with 7.2 tons of CO2 per capita, while the world averages 6.3 tons per capita.

UNICEF has dubbed the climate crisis as a “child rights crisis”, as unhindered carbon emissions and extreme weather threaten access to education, health, nutrition and the future. Research concurs: air pollution is already linked to poor birth outcomes and increased risk of cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. Heat waves are triggering mental health issues. Both are translating into “lowering academic performance as well as the wider disruption of missed school days,” UNICEF noted.

The United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child also stated that water scarcity, food insecurity, physical trauma of sudden and slow-onset events, vector-borne and water-borne diseases — hastened by climate change — are “disproportionately borne by children”.

Source: Global Climate Litigation Report: 2023 Status Review

How have the governments responded?

It comes down to cause and effect: countries so far have rejected any relationship between climate change and its impact on human health. For instance, Greece, in its submissions, maintained that the effects of climate change “do not seem to directly affect human life or human health.” This is even as the country witnessed devastating wildfires which razed 72,000 hectares of land and eroded people’s livelihoods earlier this year, in what was Europe’s largest fire according to the European Commission.

The Portuguese and Irish governments have dismissed these concerns as ‘future fears’, arguing that there is no evidence to show climate change poses an immediate risk to their lives, and their claims rest only on “mere assumptions or general probabilities.”

Other nations have argued that they are on track to achieve climate targets formulated to safeguard the interests of their citizens. The U.K. has submitted evidence of their proactive climate action, highlighting their 10-point plan and ‘concrete steps’ to achieve net zero emissions by 2050. Some policies like the 2030 ban on the sale of new petrol and diesel cars, however, have now been scrapped by the new Rishi Sunak government, thus diluting their defence. “Now is the time to be increasing ambition, not rolling back on existing commitments,” said Gerry Liston of GLAN, adding that the U.K.’s new policy is “not only senseless and immoral”, but also “illegal.”

The age of climate lawsuits

The European Convention on Human Rights has jurisdiction over 47 member states. Two other cases remain pending before the Grand Chamber. In Verein Klimaseniorinnen Schweiz and Others v. Switzerland, more than 2,000 women took Switzerland to court arguing their lives and health were under threat due to climate change, and it is incumbent upon the state to protect their human rights. “The Court has recognised the urgency and importance of finding an answer to the question of whether states violate the human rights of elderly women by not taking the necessary climate protection measures,” said Rosmarie Wydler-Wälti, co-president of Senior Women for Climate Protection Switzerland, to Greenpeace.

The second case was filed in March this year: the former mayor of France’s Grande-Synthe in Carême v. France submitted that France has insufficiently responded to the climate crisis, which is a violation of the right to life (Article 2 of the Convention) and the right to respect for private and family life (Article 8 of the Convention).

The novelty of the Duarte Agostinho case is not limited to having almost a fourth of the world’s nations defend their role in exacerbating the most pressing crisis of our times. It breathes into existence the question of current and future generations’ right to an equitable future, while emphasising that anthropogenic climate change is testing the limitations of human health.

Types of climate litigation cases

Most ongoing climate litigation falls into one or more of six categories, per the UN report:

Cases relying on human rights enshrined in international law and national constitutions

Challenges to domestic non-enforcement of climate-related laws and policies

Cases to keep fossil fuels in the ground

Advocacy for greater climate disclosures and an end to greenwashing

Corporate liability and responsibility for climate harms

Cases addressing failures to adapt to the impacts of climate change.

Earlier this year, a Montana court ruled the State’s use of fossil fuels violates people’s constitutional rights. In Austria, 12 children under the age of 16 argued the government needs to toughen its climate goals. Students from Vanuatu are engaged in a legal struggle at the world’s highest international court, asking the chambers to codify in law the obligations of countries to address “climate change and other parts of the environment for present and future generations.”

The implications and legal validity of youth-led climate trials are unclear, but experts acknowledge that lawsuits are transforming the climate litigation landscape: unchecked carbon emissions violate people’s fundamental rights, jeopardise young people’s claim to a healthy future, while also placing climate science at the centre of litigation to counter misinformation and denialism. The United Nations report noted the rising climate litigation is a testament to the “strong human rights linkages to climate change”, which can translate into “increased accountability, transparency and justice, compelling governments and corporations to pursue more ambitious climate change mitigation and adaptation goals.”

Nathan Baring, a 23-year-old plaintiff who fought a federal lawsuit in the U.S. in 2015, told a media house: “Without [a trial], justice can’t be done because you can’t establish a factual record and you can’t call out sometimes blatant falsehoods that the government is sharing. It’s necessary.”