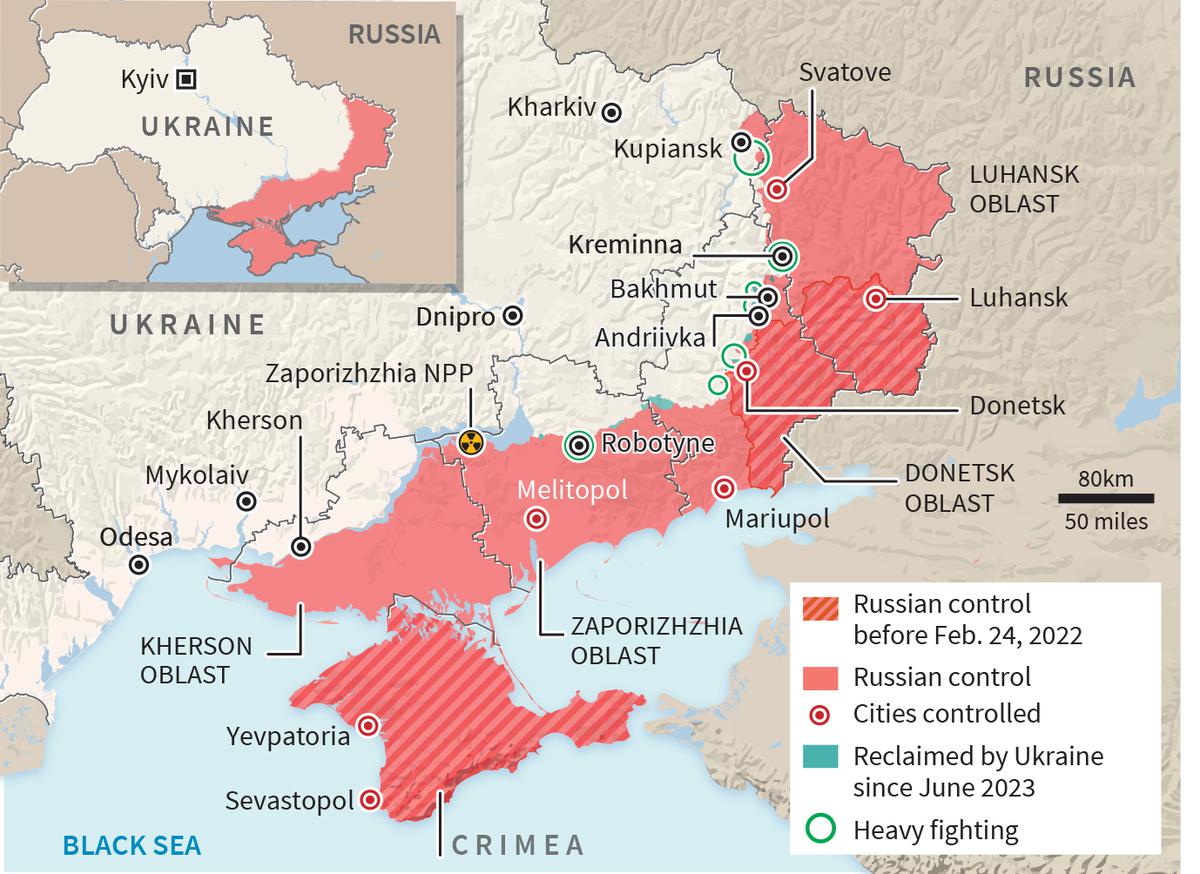

The story so far: Ukraine, which launched a counteroffensive against the invading Russian troops with advanced western weapons and NATO-trained soldiers in June, has made incremental territorial gains, but is yet to clinch a major breakthrough. Three months later, as the offensive grinds on, the Ukrainians have said that they would continue fighting to reclaim the land lost to the Russians and have asked for more military aid from the West. The U.S. and its allies seem willing to provide more assistance, but there is scepticism on whether Ukraine would meet its military objectives.

What was Ukraine’s original plan?

Ukraine had prepared for months before it launched the counteroffensive in June. In the preceding months, its Western allies had supplied highly advanced weapons, including Patriot missile defence systems, HIMAR and MLRS rockets, Stryker and Bradley armoured vehicles, Challenger and Leopard 2 main battle tanks and Storm Shadow long-range cruise missiles, besides artillery shells and ammunition. The plan, as leaked U.S. classified documents show, was to conduct a classic blitzkrieg — a lightning operation with an armoured strike force piercing through Russia’s lines of defence, capturing territories and delivering a blow to the Russian positions in eastern and southern Ukraine.

Kyiv opened three axes in its counteroffensive — Orikhiv in the south (in Zaporizhzhia); Velyka Novosilka in the Zaporizhzhia-Donetsk border area in the middle of the frontline and Bakhmut in Donetsk (east). The main objective was to reach Melitopol and the Sea of Azov to cut off Russia’s “land bridge” from the mainland to Crimea — the Black Sea peninsula it annexed in 2014 through a controversial referendum — and gain territories in the east. If Russia loses Melitopol, it would put pressure on its hold on Crimea, disrupt its supply lines and allow the Ukrainians to target Berdyansk and Mariupol further north.

What happened to the strategy?

Ukraine’s plan to take a quick victory against Russian forces was doomed to fail from the very beginning, wrote John Mearsheimer, American international relations scholar. He said that there were 11 blitzkrieg operations since modern tanks arrived on the battlefield and in most cases, the attacker with substantially higher capabilities against the defender tasted victory, what he calls an “unfair fight”. In the case of Ukraine, Russia had built three lines of defences along the frontline with trenches, landmines, heavy weapons and other fortifications. The prolonged battle for Bakhmut (which culminated in the Russians taking the city in May) pinned down thousands of Ukrainian troops in the eastern city, while providing more time to the Russians to build their defences. Ukraine, which is reliant on old Soviet-style fighter jets, also lacked advanced air cover, which is imperative for any blitzkrieg operation.

So, when Ukraine finally launched the counteroffensive, its troops jumped straight into the traps laid by Russia. According to a report in The New York Times, Ukraine lost some 20% of the weaponry it got from the West in the first two weeks of the counteroffensive. As Ukraine realised that the blitzkrieg was not working, it changed its tactics from attempting for a major thrust into the Russian defences to small operations targeting the rear of Russia’s military machine, while employing long-range fire to attack the enemy’s supply lines. This allowed Ukraine to take some small villages along the frontline, but breaching the Russian defences remains a distant goal.

How did Russia slow down Ukrainian advances?

In the initial phase of the war, Russia made a lot of mistakes. Its plan was to capture territories quickly and hold them with a limited number of forces (some 1,90,000 troops were mobilised for the invasion). But when the Ukrainians resisted, denying a quick victory to Russia, it both exposed Moscow’s weakness and opened new avenues for the West to step in. Last year, Russia was forced out of Kharkiv by a swift Ukrainian advance; and later on, Moscow decided to pull back its troops from the western bank of Dnipro in Kherson. Since then, Russia has changed its focus from offensive operations to defence, its traditional forte. Vladimir Putin, the Russian President, ordered a partial mobilisation, drafting some 3,00,000 men, who the Russians hoped would solve the manpower shortage that plagued their initial thrust into Ukraine.

Since the Kherson pullout, Russia’s territorial advances were limited to Donetsk — it took Soledar in January and Bakhmut in May, in operations mostly involving the Wagner private military company. Besides trenches filled with explosives and miles-deep trip-wired or booby-trapped mines, Russian troops also used the ISDM Zemledeliye mine-laying system that spread mines from rockets at a rapid pace. On the frontline, Russia used this tactic, according to Ukrainian officers, to rapidly re-mine cleared areas, often trapping advancing Ukrainian troops within circles of minefields.

In the early stage of the war, Russia lost dozens of its fighter jets; now, analysts note, the Russian Air Force remains intact, though it still lacks air superiority. They also use precision guided bombs, released from low altitude jets or attack helicopters, targeting positions well beyond Ukraine’s defence lines. They have also deployed attack helicopters, anti-tank missiles and artillery on the frontline, which made advances extremely difficult for the Ukrainian troops. As Ukraine makes slow progress on the battlefield, it also gives the Russians time to refortify the defence lines or re-mine the cleared areas.

What has been the West’s response?

The U.S. intelligence agencies had expressed their scepticism about the counteroffensive well before it was launched. In February, leaked U.S. intelligence documents showed the bleak assessment of the counteroffensive by Washington. According to documents, labelled as “top secret”, U.S. agencies had assessed that Ukraine’s operation would result “only in modest territorial gains” and could fall “well short” of its goals. The U.S., which has supplied military aid worth $40 billion to Ukraine since the war began, seemed to have realised weeks into the counteroffensive that things were not looking good for Ukraine. In early July, the Biden administration announced that it would send cluster munitions to Ukraine, which have been banned by over 100 countries for the indiscriminate harm they cause to civilians. As Ukraine’s offensive went on with meagre results, questions started rising from allies about its tactics. According to a Financial Times report, U.S. officials say Ukraine was “risk-averse” and failed to execute an effective campaign, combining infantry, artillery and air power. Ukrainian soldiers challenged the U.S. criticism asking when was the last time American troops fought a conventional war with an equal force on the battlefield.

Gen. Mark A. Milley, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff said in a recent interview that the U.S. has been clear about the challenges before Ukraine. “I had said a couple of months ago that this offensive was going to be long, it’s going to be bloody, it’s going to be slow,” he said. “And that’s exactly what it is: long, bloody and slow, and it’s a very, very difficult fight.” A latest U.S. intelligence assessment stated that the counteroffensive would fail to reach Melitopol, a key Ukrainian goal, according to a report in Washington Post that cited unnamed American officials.

But these difficulties do not mean that the U.S. is having a rethink in its approach. Last week, President Joe Biden decided to send long-range army tactical missile systems (ATACMS) to Ukraine, which would allow Kyiv to target Russian positions well beyond the frontline. U.S.-supplied Abrams main battle tanks are set to enter the battlefield soon, according to the Pentagon. President Biden is also seeking an additional $24 billion in aid for Ukraine.

Where does it leave Russia?

The U.S. had a twin approach towards Russia’s invasion. One was to arm Ukraine to beat Russia in the battlefield and the other was to weaken Russia through economic sanctions. This approach has had mixed results. The way Russia is withstanding Ukraine’s counteroffensive suggests that Moscow has learnt from its early mistakes and is adapting itself rapidly to new battlefield realities. Russia also came up with ways to work around sanctions and export controls so that its defence production would not be affected.

If Russia could make 100 tanks a year before the war, now they are manufacturing 200, according to a recent NYT report. Russia is also on track to make two million artillery shells a year, twice the number of shells it produced before the war, according to the report. But at the same time, sanctions have affected Russia’s economy in general. Russia has also taken huge casualties. According to U.S. estimates, Russia’s military has suffered greatly with more than 2,70,000 killed or wounded.

Besides, in recent months, Ukraine has also taken the war to Crimea, the Black Sea and even to Moscow through drones and missiles. Particularly in the Black Sea, Russia’s fleet, which is based off Crimea, comes under repeated Ukrainian attacks.

The prolonged war in Europe has contributed to an erosion of Russian power in its periphery, particularly in the Caucasus (where Azerbaijan dismantled a Russia-mediated ceasefire and took over the disputed Nagorno-Karabakh territory using force). Russia has also helplessly witnessed NATO expanding further towards its border after it launched the Ukraine war. However, despite these setbacks, Mr. Putin seems determined to continue fighting a war of attrition, while Ukraine is trying to escape attrition with quick battlefield gains. In either scenario, peace remains a distant idea.