The story so far:

On Monday, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences announced that the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences for 2023 was being awarded to Harvard University Professor Claudia Goldin for “having advanced our understanding of women’s labour market outcomes”. Her work, it said, is the “first comprehensive account of women’s earning and labour market participation through the centuries”. Professor Goldin is only the third women to have won the prize (for Economics) and the first to do it solo.

What is her research about?

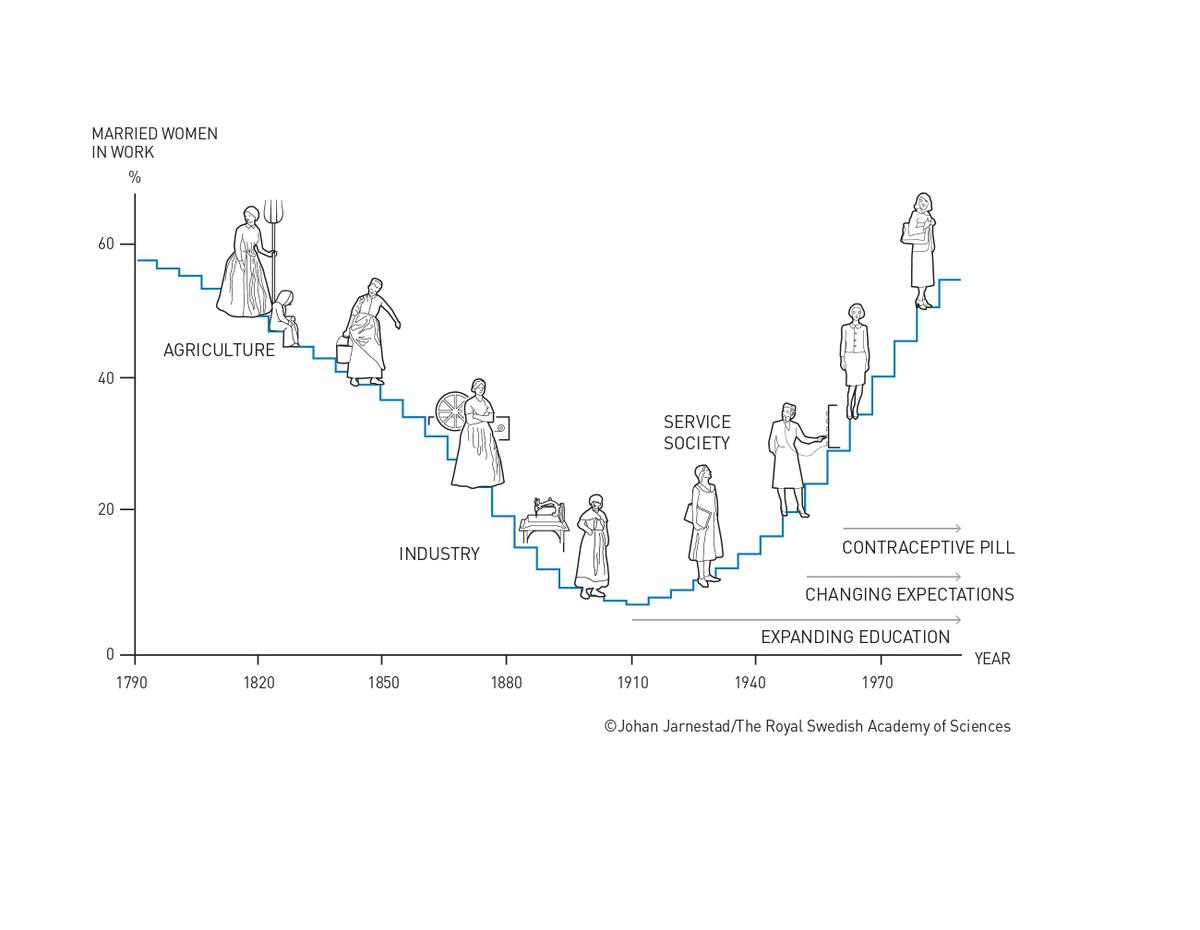

Professor Goldin trawled through the archives of about 200 years of the United States to demonstrate how and why gender differences in earnings and employment rates have changed over time. The most significant of her observations was that female participation in the labour market did not exhibit an upward trend over the entire period, but rather a U-shaped curve. In other words, economic growth ensuing in varied periods did not translate to reducing gender differences in the labour market. She demonstrated that several factors have historically influenced and still influence the supply and demand for female labour. These include opportunities for combining paid work and a family, decisions (and expectations) related to pursuing education and raising children, technical innovations, laws and norms, and the structural transformation in an economy.

According to her, the most important in the unequal paradigm “is that both lose”. She told Social Science Bites blog earlier in December, “Men are able to have the family and step up because women step back in terms of their jobs, but both are deprived. Men forgo time with their family and women often forgo their career”.

How did female participation move between the agrarian and industrial era?

The participation of married women decreased with the transition from an agrarian to an industrialised society in the early nineteenth century. It started to increase again with the growth of the services sector in the early nineteenth century. The first of Professor Goldin’s observations was about how female participation in labour force was incorrectly assessed and thereby, (incorrectly) stated in Censuses and public data. For example, a standard practice entailed categorising women’s occupation as “wife” in records. This was incorrect because the identification did not account for activities other than domestic labour such as working alongside husbands in farms or family businesses, in cottage industries or production setups at home, such as with textiles or dairy goods.

According to Professor Goldin, correcting the data about female participation established that the proportion of women in the labour force was considerably greater at the end of the 1890s than was shown in the official statistics. They enumerate that the employment rate for married women was three times greater than the registered Census.

She also observed that prior to the advent of industrialisation in the nineteenth century, women were more likely to participate in the labour force. This was because industrialisation had made it harder for married women to work from home since they would not be able to balance the demands of their family. Even though her research held that unmarried women were employed in manufacturing during the industrial era, the overall female force had declined.

These two factors combined form the basis of the claim that there is no historical consistency between female engagement in the overall labour force and economic growth.

What happens when the curve moves upwards?

The beginning of the twentieth century marked the upward trajectory for female participation in the labour force. According to Professor Goldin, technological progress, the growth of the service sector and increased levels of education brought an increasing demand for more labour. However, social stigma, legislation and other institutional barriers limited their influence.

Two factors are of particular importance here, namely, “marriage bars” (the practice of firing and not hiring women once married) and prevalent expectations about their future careers. The former, according to Professor Goldin, peaked during the 1930s’ Great Depression and the ensuing years — preventing women from continuing as teachers or office workers. About expectations, Professor Goldin notes that women at varied points were subject to different circumstances when deciding on their life choices. Their decisions could be based on an assessment of expectations that might not come to fruition.

How are expectations becoming a factor?

The Harvard professor observed that in the early twentieth century, for example, women were expected to exit the labour force upon marriage. . When things turned marginally in the second half of the century, married women would return to the labour force once their children were older. However, this meant a reliance on educational choices that were made previously, as the author notes, at a time when they were not expected to have a career. The “underestimation” was overcome in the 1970s when young women invested more in their education.

As the Nobel Prize academy puts it, the exit for an extended period after marriage “also explains why the average employment level for women increased by so little, despite the massive influx of women into the labour market in the latter half of the century.”

Another pivotal factor was the introduction of birth control pills. This created conditions for women to plan their careers better. Even if the pill influenced educational and career choices, this did not translate to the disappearance of the earnings gap between men and women, though it became “significantly smaller since the 1970s”.

When did pay discrimination emerge?

According to Professor Goldin, pay discrimination (that is, employees being paid differently because of factors such as colour, religion or sex, among others) increased significantly with the growth of the services sector in the twentieth century. This was surprisingly at a time when the earnings gap between men and women had decreased and when piecework contracts were being increasingly replaced with payments on monthly basis. Thus, the expectations paradigm emerged again, as employers would prefer employees with “long and uninterrupted careers”.

Nobelprize.org

What do her books convey about her work?

In 1990, Professor Goldin published Understanding the Gender Gap: An Economic History of American Women (Yale University Press). In it, she wrote that her study of the female labour force in the U.S. had shown that the advance in the economic status of women and the gender divide in the workplace were due to “longstanding societal trends.” Among other things, she had researched the men-women wage gap and the emergence of “wage discrimination”, and the experience of women in the labour force.

In 2008, she published The Race Between Education and Technology (Harvard University Press), co-written with Lawrence Katz, in which they studied how the fact that America had become the richest nation at the dawn of the 20th century impacted women. They drew a connection between the “American Century” and the “Human Capital Century”, pointing at the role of education in economic growth and individual productivity. But they also found that the benefits of economic growth were not necessarily evenly distributed. By the 1970s, “rising inequality, lagging productivity for a prolonged period, and a rather non-stellar educational report card led many to question the qualities” that once made America stand out. “The slowdown in the growth of educational attainment,” they write, “has been most extreme and disturbing for those at the bottom of the income distribution, particularly for racial and ethnic minorities.” Their research showed that in the first half of the century, education raced ahead of technology, but later in the century, technology raced ahead of educational gains. They attribute the sharp rise in economic inequality largely to “an educational slowdown.” On the positive side, however, Goldin and Katz found that educational advances for women were substantial.

Currently, the Henry Lee Professor of Economics at Harvard University, she edited Women Working Longer: Increased Employment at Older Ages (University of Chicago Press) with Katz in 2018. The writers, and a host of other essayists, noticed a trend that American women, in their fifties to the seventies, were working more than ever, and that this increased participation in the labour force started around the 1980s. In nine chapters, the writers address the reasons — education, work experience, disruption in household finances, access to retirement benefits and so forth — for this and what the future held for women working longer.

In her 2021 book, Career & Family (Princeton University Press), Goldin traced a century-long journey of women to close the gender wage gap, writing in detail about what has held women back, and what still does. She chose five groups of women through the ages, starting with Group One who had to choose between the two goals of career and family, and Group Five now who aspire to, and often succeed at, both. She talked about the power of the contraceptive pill which helped many women make better marriage and career choices. Alongside describing the fight for women who faced disparate treatment at the workplace, she also brought up an equally important issue, that of couple equity in the house, and the importance of sharing house work. Her hope for the future is that women have a career as well as a spouse who wants what they want.

With inputs from Sudipta Datta.