Venezuelan migrants board a repatriation flight as a part of an immigration enforcement process, at the Valley International Airport, in Harlingen, Texas, U.S. October 18, 2023.

| Photo Credit: Reuters

Deportation flights of Venezuelans from the U.S. resumed Wednesday with a first plane of more than a hundred migrants landing back in their economically troubled country under the Biden administration’s latest attempts to deal with swelling numbers of asylum-seekers.

This is the first time in years that U.S. immigration authorities are deporting people to the South American nation, marking a significant concession by the government of Venezuela’s President Nicolás Maduro to a longtime adversary.

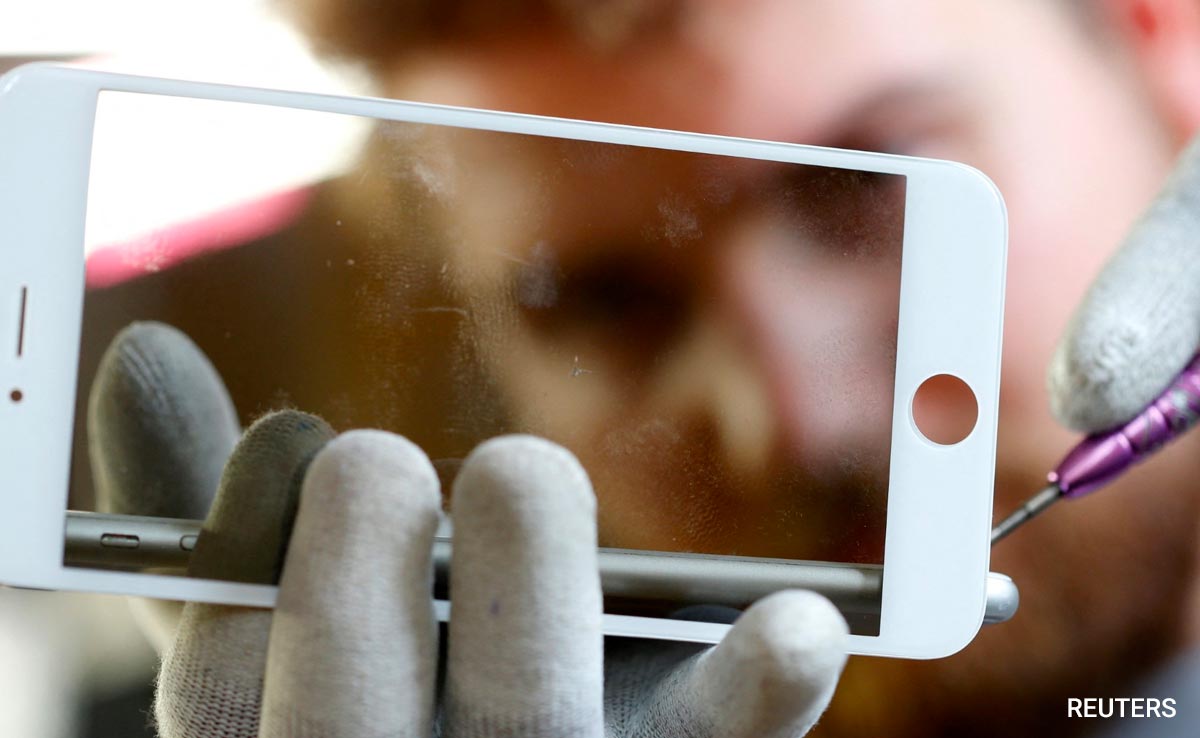

The first plane, a Boeing 737 jet, took off from the Texas border city of Harlingen and touched down in Miami before arriving hours later outside Caracas, Venezuela’s capital. The roughly 130 passengers were Venezuelan women and men who were shuttled to the plane on buses, and wore wrist and ankle restraints. As they boarded, U.S. immigration officers patted them down.

Biden’s administration said it plans to have “multiple” deportation flights a week to Venezuela, according to a U.S. Transportation Department waiver on travel restrictions, which would place Venezuela among the top international destinations for U.S. immigration authorities.

The first flight came a day after the country’s government and opposition agreed to work on electoral conditions, which triggered the U.S. Department of Treasury to announce some sanctions relief on Venezuela’s oil, gas and gold mining sectors hours after the airplane landed at the airport in Maiquetia.

“I am glad that today, in compliance with the agreements discussed and signed between the authorities of Venezuela and the government of the United States, the first group of Venezuelans who have been repatriated have returned,” Maduro said during televised remarks that also addressed electoral conditions that will affect the country’s 2024 presidential election.

State television showed footage of migrants in face masks exiting the plane, getting health tests and answering questions from officials at the airport near Caracas. Maduro’s government has blamed migration on economic sanctions.

Corey Price, an acting executive associate director for U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, said those who were prioritized for the flights include recent arrivals as well as migrants who have committed crimes in the U.S. Border Patrol Chief Jason Owens said the passengers had illegally entered the U.S. between ports of entry.

“This flight to Venezuela is the first I’ve seen in my career of an entire charter flight of Venezuelans going back to their country. And we plan on having several more of these in the coming days and weeks,” Price said.

The deportees will find a homeland that is still in the midst of complex social, political and economic crisis.

The situation has evolved since a global drop in the price of oil — Venezuela’s most valuable resource — a decade ago and mismanagement by the self-proclaimed socialist government pushed the country into a downward spiral. People are grappling with constant food-price hikes and business closures, and workers try to meet their needs with a monthly minimum wage of $3.70 that’s barely enough to buy a gallon of water.

Mr. Maduro’s government has said it will make resources available to help deported migrants.

The U.S. government employs a fleet of charter carriers known collectively as ICE Air. Using charter airlines though, these flights, which typically carry 135 migrants, will fly to Venezuela from unspecified airports in the United States, according to the Department of Homeland Security. They will be for Venezuelans who have received final removal orders, which are issued after losing an asylum bid or to those who weren’t able to seek humanitarian protection.

The flights are in response to “an increase in migration from Venezuela that is straining immigration systems throughout the hemisphere — including in the United States,” the Transportation Department said in its waiver.

The U.S. has struggled for years to deport people to countries with which it has strained diplomatic relations, including Venezuela, Cuba and Nicaragua. After a hiatus of more than two years, Cuba allowed for the resumption of U.S. deportations in April, with deportation flights there operating only about once a month.

The U.S. government hopes the recent threat of deportation will be enough to make Venezuelans reconsider trying to enter the United States illegally — and opt instead for the online appointment system to make asylum claims or attempt other legal paths. But it has not deterred many people from continuing to migrate.

Venezuelan migration to the U.S. tapered off a year ago when the Biden administration agreed to allow Venezuelans to enter the country if they applied online with a financial sponsor who also arrived at the airport. More than 61,000 Venezuelans came on that route since last October.

The restart of the deportation flights takes places just weeks after the Biden administration announced that it is granting temporary legal status to hundreds of thousands of Venezuelans that have arrived in the U.S. by July 31.

The temporary status makes it easier for them to get work authorization and stop deportation orders.

Experts and immigration attorneys are urging Venezuelans to apply to TPS to prevent their repatriation.

“Venezuelans who have not applied for TPS and have deportation orders could be affected,” said Rachel Leon, an immigration attorney in Florida. “Those who are eligible for TPS should apply as soon as possible to avoid facing deportation.”

At the same time, Mexico agreed to let in some Venezuelans who were deported from the U.S. after crossing the border illegally, recognizing that Venezuela wouldn’t.

The lull was short-lived. In August, Venezuelans were arrested more than 22,000 times on charges of crossing the border illegally, fourth behind people migrating from Mexico, Guatemala and Honduras. Many head to New York, Chicago and other major U.S. cities, overwhelming shelters and temporary housing there.