With Israel intensifying its bombardment of Gaza, in which more than 7,700 people were killed in 22 days, fears of a wider regional war are also rising. Israel started bombing Gaza, a tiny, defenceless enclave of 2.3 million people, who have been sandwiched between Israel proper and the Mediterranean Sea, after Hamas, an Islamist militant group that controls the land strip, carried out a cross-border raid on October 7, killing at least 1,400 Israelis. After Israel started the retaliatory strikes, Hezbollah, a Lebanese Shia militant group that had fought Israel in the past, fired rockets into the Shebaa Farms, a Lebanese territory on the border that Israel occupies, showing “solidarity” with the Palestinians. Last week, Hezbollah’s leader Hassan Nasrallah met Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad leaders and offered support for the “Palestinian resistance”. Some Hezbollah fighters also tried to infiltrate into northern Israel after the Gaza war began. Israel responded with heavy shelling of southern Lebanon. As tensions rise, the world is watching whether Hezbollah would open another front or Israel carry out pre-emptive strikes in Lebanon, widening the conflict.

Also Read | UNGA vote on Gaza | India defends abstention, says resolution should have referred to October 7 terror attacks on Israel

Ironically, the roots of Hezbollah go back to Israel’s 1982 war on Lebanon, which the then Likud Prime Minister, Menachem Begin, said would bring “forty years of peace for Israel”. Lebanon was in the grip of a devastating civil war that began in 1975. According to Lebanon’s post-French Constitution, power was divided among the country’s different communities — the Presidency is reserved for Christians, the Premiership for Sunnis and the Speakership for the Shias. Roughly 40% of Lebanon’s population are Arab Shias. The influx of the Palestinian refugees into Lebanon and the relocation of the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO) to Lebanon from Jordan in 1971 would create fissures in the country’s delicate confessional system, which would lead to the civil war. While the Sunnis and Maronite Christians were the powerful sects, Shias were the invisible majority, sidelined by the major players and post-colonial institutions.

Israel attacked Lebanon in 1978 and 1982, first to push the PLO out of the border region and then out of the country. In 1982, the PLO would agree to leave Lebanon, but one community that bore the brunt of Israel’s disproportionate bombing was the already marginalised Shias.

Three years earlier, a geopolitical earthquake had shaken West Asia — in Iran, which was an American ally, Shia Mullahs captured power after bringing down a thousands of years old monarchy. Iran, which was already fighting a conventional war with Iraq (1980-88), sensed an opportunity in Lebanon’s chaos. The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps of the Iranian regime helped mobilise thousands of Shias in Lebanon in 1982 to form a loose network of what was then unofficially called the ‘Islamic Resistance’.

Early attacks

One of the first targets of the Islamic Resistance was the Multinational Forces (MNF) deployed in Lebanon. In April 1983, the U.S. Embassy in Beirut was bombed, killing 63 people. In October, 305 people, mostly American and French soldiers, were killed in suicide attacks on their military barracks. Following these attacks, the MNF would leave the country, providing the first victory to the newly organised Shia militants. Israeli troops retreated to a “security zone” in southern Lebanon. In 1985, the Islamic Resistance would come up with a manifesto, calling for the destruction of the state of Israel, vowing to oust occupied forces from Lebanon and declaring allegiance to Iran’s Supreme Leader. According to some reports, it was Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the Supreme Leader, who picked the name ‘Hezbollah’ (literally ‘the Party of God’) for the new movement.

Over the years, Hezbollah has built sprawling social, political and military networks with deep roots in Lebanon’s Shia community. In southern Lebanon, a Shia stronghold, it carried out a disciplined, effective, popular guerilla war against the occupying Israeli forces, turning the ‘security zone’ into what Adam Shatz calls an ‘insecurity zone’. The party organisation has been built in a Leninist order, centralising authority in the hands of the Secretary General. The chief would oversee a seven-member Shura council, like the Polit Bureau of a communist party, and then there are sub councils. Their social network caters to the Shia working class, offering support, including healthcare and education assistance, in a country where the state is systemically weak, while the political and parliamentary councils have played the role of a kingmaker in Lebanon’s fractured polity since 1992, when Hezbollah participated in the elections for the first time. Yet, the most important arm is the Jihad Council, which controls its military activities.

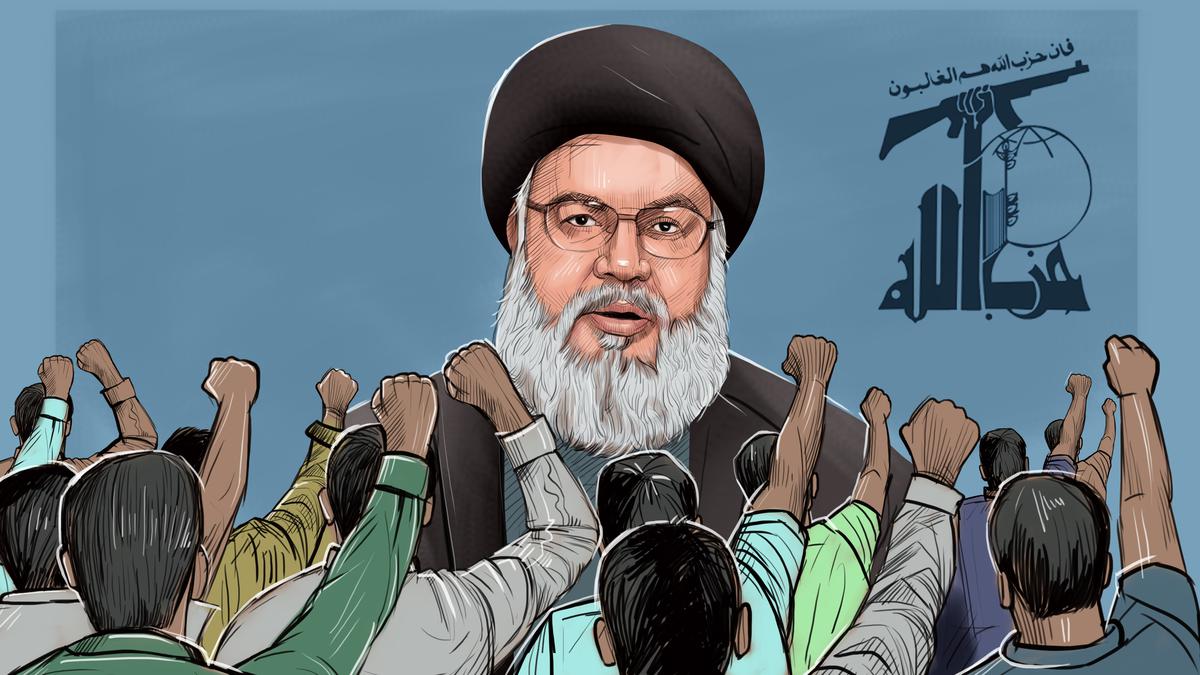

Israel assassinated Hezbollah’s co-founder Abbas al-Musawi in 1992 as part of a policy of targeted killings to weaken rival outfits. But the man who succeeded Musawi, Hassan Nasralla, turned Hezbollah into a socio- politico-militant giant, “a state within the state”, though it has been designated as a terrorist outfit by Israel and several of its allies. In 2000, after 18 years of occupation, Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak decided to unilaterally withdraw from southern Lebanon, which Hezbollah celebrated as “the first Arab victory in the history of Arab-Israeli conflict”. But Israel’s withdrawal would not quieten the Lebanese border. Hezbollah said it would continue to fight the Israelis as long as its occupation of Shebaa Farms and Palestinian territories continues. In its 2019 updated manifesto, Hezbollah reiterated its commitment for the destruction of Israel.

War with Israel

In 2006, after Hezbollah carried out a raid and abducted two Israeli soldiers, Prime Minister Ehud Olmert declared war against the militant group. The war lasted for over 30 days and even on the last day of fighting, Hezbollah launched hundreds of rockets into Israel. Israeli air strikes and ground attacks destroyed much of Hezbollah’s military infrastructure, but the group survived, and emerged politically stronger in Lebanon. In the subsequent years, Hezbollah rebuilt its military power, mainly with help from Iran. From the 1980s, Syria’s Baathist regime has been a conduit between Iran and Hezbollah. When Bashar al-Assad’s regime was losing control in the midst of the Syrian civil war, Nasrallah despatched thousands of soldiers to fight alongside the Syrian Army. Under Russian air cover and with support from Iran, the Syrian Army, Hezbollah and other Shia militias turned around the civil war. Hezbollah emerged stronger out of the Syrian conflict, with newly gained battlefield experience. It has also strengthened the Iran-Syria-Hezbollah axis. In recent years. Israel has carried out repeated air strikes inside Syria, mainly targeting Iranian supplies for Hezbollah.

Israel sees Hezbollah as a potent rival, unlike other non-state actors, including Hamas. According to the International Institute for Strategic Studies, London, the militia has up to 20,000 active fighters and as many reservists, with an arsenal of small arms, tanks, drones, and long-range rockets. Last November, while briefing about Israel’s past conflicts with Hezbollah on the Lebanese border, an Israeli Brigadier told this writer they never underestimated Hezbollah, which “has now amassed more than 1,00,000 rockets”. “Hezbollah is a tough enemy. They have very good military equipment. They are very well-trained,” he said, requesting anonymity. That Israel has mobilised 3,50,000 troops, including all reservists, suggests that it is taking the risk of a wider war seriously. Hezbollah, on the other side, keeps everyone guessing, while reiterating its rhetorical support for Hamas. “We are fully ready to fight Israel when time comes,” says the ‘Party of God’.