It’s funny when you think about the fact that the Halley’s Comet is named after an English astronomer who lived in the 17th-18th Centuries, despite having been spotted and observed for over two millennia. In fact, this astronomer is considered the discoverer of the comet, even though he certainly wasn’t the first human to take note of it.

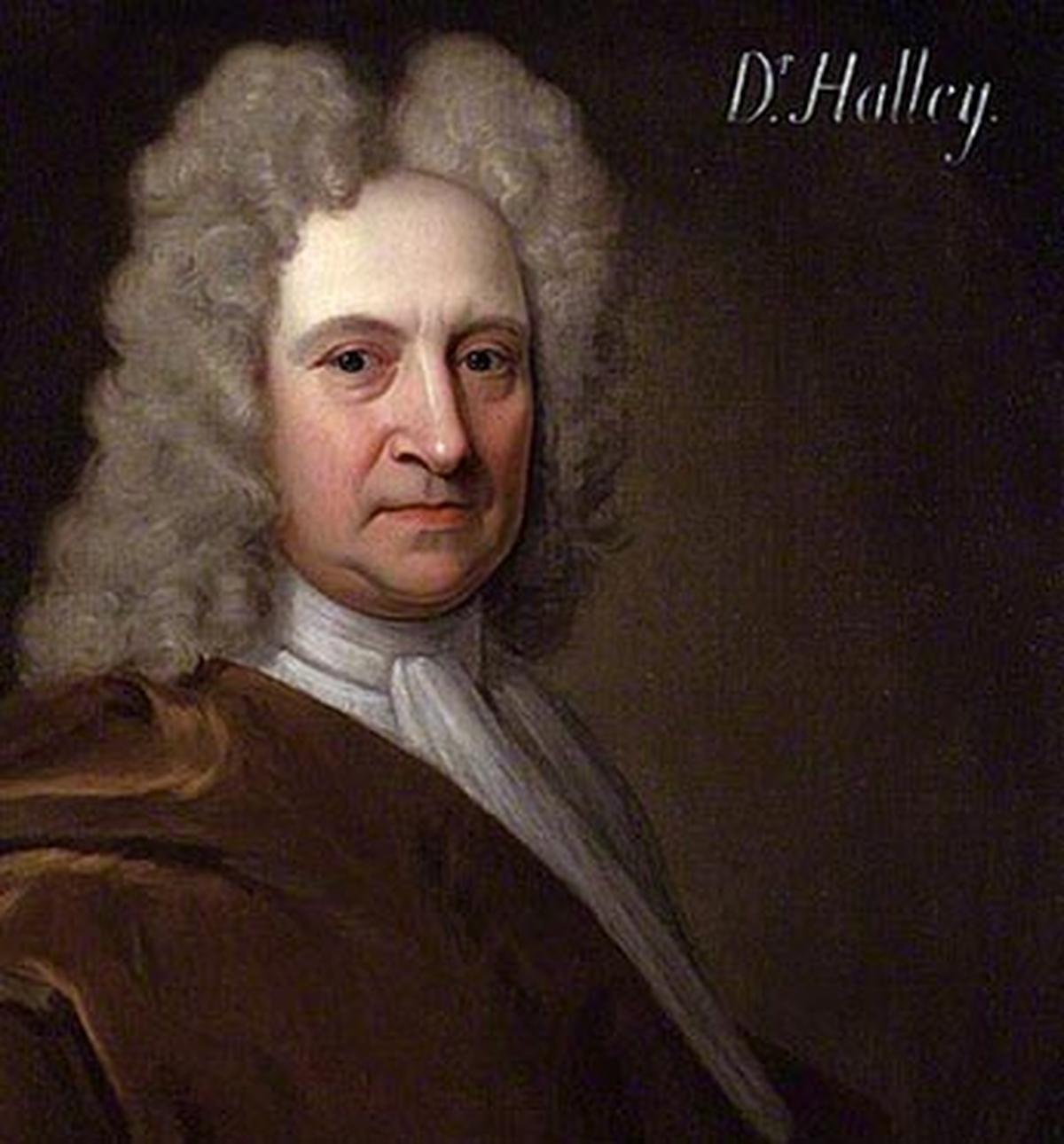

The astronomer in question is the Englishman Edmond Halley, who was also a mathematician and physicist in addition to being an astronomer. He succeeded English astronomer John Flamsteed as the second Astronomer Royal in Britain in 1720.

Calculus + astronomy

It was during his time as an assistant to Flamsteed that he did the work that makes him the discoverer of Halley’s comet and also gives it his name. A sound mathematician, Halley brought together astronomy with a nascent field of mathematical study called calculus to compute the parabolic paths of comets.

Edmond Halley

| Photo Credit:

National Portrait Gallery London / picryl

He worked out the parabolic orbits of many comets that had been recorded over the last few centuries and he had his results by 1705. When comparing the results, he was to identify that the orbits of the comets observed by famed German astronomer Johannes Kepler in 1531 and 1607, and the comet that he himself observed in 1682 were, in fact, nearly identical.

As a thorough scientist, Halley next traced it back even further. To his astonishment and delight, Halley was able to ascertain that there had been a number of recorded instances where comets had been observed in a similar orbit once about every 75 years, including the one seen by Italian painter Giotto di Bondone.

Predicts future occurrence

Halley correctly concluded that these weren’t different comets taking identical paths, but were, in fact, the same comet coming periodically in different years. He then went a step further and proved that scientists could employ science to predict a future occurrence, something that astrologers boast without always achieving success.

Halley stated that this comet, now officially designated 1P/Halley, would next be in the Earth’s vicinity in 1758. And even though he wasn’t around as he died in 1742, Halley’s Comet made its way in December 1758. From then onwards, the comet that bears Halley’s name has made its appearance in 1835, 1910, and 1986. Almost like clockwork.

Even though much had been learnt about the comet by the time it made its appearance in 1910, there was plenty of apocalyptic hype surrounding its return in that year. As the telescopes of the time were still incapable of tracking Halley’s comet throughout its orbit, anticipation mounted as the year drew closer.

Anticipation turns into concern

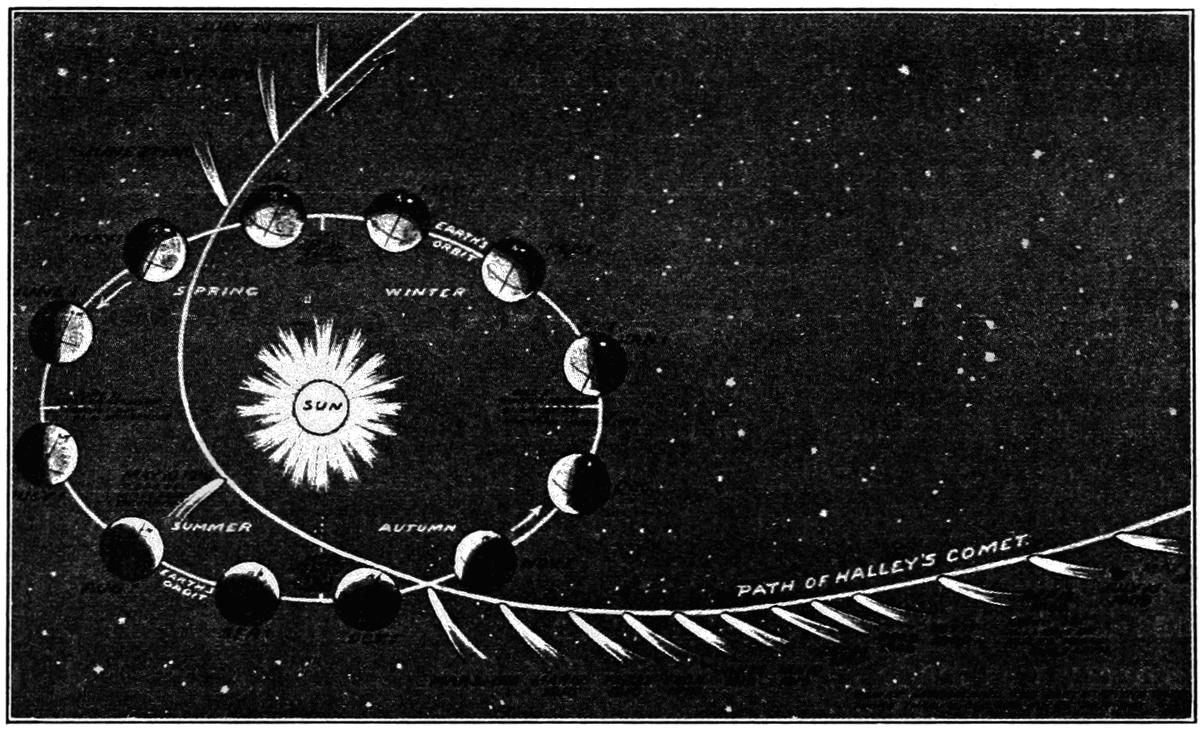

With the comet expected to follow a close passage near Earth, there was increasing expectancy of spectacular views. When astronomers realised that the Earth would in fact pass through the comet’s 25-million-kilometre-long tail, some of the excitement turned into concern.

Infographic from the January 1910 issue of Popular Science Monthly magazine showing the path of Halley’s Comet.

| Photo Credit:

Wikimedia Commons

The technique of spectroscopy was employed on Halley’s Comet by the Yerkes Observatory in the U.S. By analysing light to show the composition of celestial objects, the observatory announced the discovery of cyanogen, a deadly poison, in the comet’s tail in February.

When Camille Flammarion, a French astronomer and author, said that the cyanogen “would impregnate the atmosphere and possibly snuff out all life on the planet,” the story was immediately lapped up by popular media around the world and splashed across many a front page. Many other scientists’ attempts to allay the fears fell flat.

Comet pills and all-night vigils

With the Earth’s passage through Halley’s tail set for May 19, concerns mounted among the public as the day drew nearer. Those looking to maximise the panic hatched nefarious schemes, selling comet pills that were supposed to protect the person from the effects of the poison. Even all-night prayer vigils were held by a number of religious organisations.

Halley’s Comet on May 19, 1910 as photographed at the Lowell Observatory.

| Photo Credit:

Lowell Observatory and the National Optical Astronomy Observatories / ESA

May 19 came and went, but life on Earth had certainly not been “snuffed out.” While the irrational folks were finally starting to shed some of their worries, the rationals had enjoyed a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, observing the comet’s passage from rooftops across the globe.

Halley’s Comet is next scheduled to make its Earth-bound visit in 2061. Let’s hope that there aren’t any doomsday predictions driving its build-up and passage that time as well.

Popular sightings

As a periodic comet with a relatively short period, Halley’s Comet has been witnessed many times throughout human history. Here are some popular sightings:

According to the European Space Agency, the first known observation of this comet took place in 239 B.C. when Chinese astronomers recorded its passage in the Shih Chi and Wen Hsien Thung Khao chronicles. There are other studies that push the first known observation even further back to 466 B.C.

In 1066, William the Conqueror invaded England and defeated King Harold at the Battle of Hastings. Shortly before this invasion, this comet was spotted and it is stated that William believed that it heralded success. The Bayeux Tapestry that honours William by depicting the Norman conquest of England has an image of Halley’s Comet.

Halley’s Comet appeared in 1301. There is reason to believe that Italian painter Giotto di Bondone’s was inspired by his sighting of this comet for his rendering of the Star of Bethlehem in “The Adoration of the Magi.”

Inter-Twain-ed

The life of American author, humorist, and essayist Samuel Langhorne Clemens, more popularly known by his pen name Mark Twain, was intertwined with that of Halley’s Comet.

Twain was born on November 30, 1835, weeks after the perihelion of Halley’s Comet during its 1835 visit.

In 1909, aware that the comet was due to make another pass the following year, Twain predicted his own death. It is believed that he said “I came in with Halley’s Comet. It is coming again next year. The Almighty has said, no doubt, ‘Now there are these two unaccountable freaks; they came in together, they must go out together.’”

Twain died on April 21, 1910, a day after the comet had reached its perihelion on that occasion.