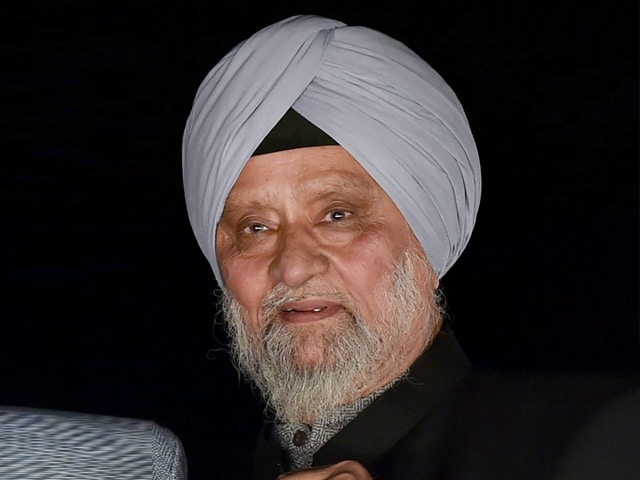

The male savannah elephant Doma and the male savannah elephant Mainos engage in greeting behaviour at Jafuta Reserve in Zimbabwe, in this undated handout picture.

| Photo Credit: Reuters

People greet each other in a variety of ways. They might say “hello,” “guten tag,” “hola,” “konnichiwa” or “g’day.” They might shake hands, bump fists, make a fist-and-palm gesture or press their hands together with a gentle head bow. They might kiss on the cheek or hand. And they might give a nice big hug.

For elephants, greetings appear to be a similarly complex affair. A study based on observations of African savannah elephants in the Jafuta Reserve in Zimbabwe provides new insight into the visual, acoustic and tactile gestures they employ in greetings, including how greetings differ depending on factors such as their sex and whether they are looking at each other.

“Elephants live in a so-called ‘fission-fusion’ society, where they often separate and reunite, meeting after hours, days or months apart,” said cognitive and behavioural biologist Vesta Eleuteri of the University of Vienna in Austria, lead author of the study published this month in the journal Communications Biology.

Elephants, Earth’s largest land animals, are highly intelligent, with keen memory and problem-solving skills and sophisticated communication.

Female elephants of different family groups might have strong social bonds with each other, forming “bond groups.” Previous studies in the wild reported that when these groups meet, the elephants engage in elaborate greeting ceremonies to advertise and strengthen their social bond, Eleuteri said.

Male elephants have weaker social bonds, and their greetings may function more to ease possible “risky reunions” – a hostile interaction. They greet mainly by smelling each other, reaching with their trunks, Eleuteri added.

The study detailed around 20 gesture types displayed during greetings, showing that elephants combine these in specific ways with call types such as rumbles, roars and trumpets. It also revealed how smell plays an important role in greetings, often involving urination, defecation and secretions from a unique elephant gland.

Elephants may greet by making gestures intended to be seen, like spreading the ears or showing their rump, or with gestures producing distinct sounds like flapping the ears forward, or with tactile gestures involving touching the other elephant.

The male savannah elephant Doma and the female savannah elephant Kariba engage in greeting behaviour at Jafuta Reserve in Zimbabwe in this undated handout picture.

| Photo Credit:

Reuters

“We found that they select these visual, acoustic and tactile gestures by taking into account whether their greeting partner was looking at them or not, suggesting they’re aware of others’ visual perspectives. They preferred using visual gestures when their partner was looking at them, while tactile ones when they were not,” Eleuteri said.

Greeting behaviour has been studied in various animals.

“Many other species greet, including different primates, hyenas and dogs,” Eleuteri said. “Animal greetings help mediate social interactions by, for example, reducing tension and avoiding conflict, by reaffirming existing social bonds, and by establishing dominance status using different behaviors.”

The new research built on previous studies of elephant greeting behavior. The nine observed elephants – four females and five males – were “semi-captive,” freely roaming their natural environment during daytime and kept in stables at night.

Greetings used by the female elephants closely matched the behavior of wild elephants. The greeting behavior of the male elephants appeared to differ from their wild counterparts. Wild male elephants tend to be solitary, forming loose associations with other elephants.

The temporal gland, midway between the eye and the ear, secretes a substance called temporin containing chemical information about an elephant’s identity or emotional and sexual state. Elephants often use their trunks to check out the temporal glands of others.

“The urine and feces of elephants also contain chemical information important for elephants, like the identity of the individual, their reproductive state or even their emotional state,” Eleuteri said.

“Elephants might defecate or urinate during greetings to release this important information. Another option is that they do this due to the excitement of seeing each other. But the fact that the elephants often moved their tails to the side or waggled their tails when urinating and defecating suggests they may be inviting the recipients to smell them. Maybe they don’t need to tell each other how they’re doing, as they can smell it,” Eleuteri added.