On World Oceans Day (June 8), we can take in the wonders of the smallest of the three major oceans right in our front yard. The Indian Ocean has been getting a lot of attention recently for its rapid warming and the outsized influence it continues to have on its peers.

As it happens, the Indian Ocean is critical today to understand the earth’s overall ocean response to increasing greenhouse gases and global warming.

Home to the deadliest storms

The Indian Ocean is famous for its dramatic monsoon winds and the bountiful rain it brings on the Indian subcontinent. The winds and the rain have evoked prose and poetry for millennia. More than a billion people depend on the moisture it supplies to quench their thirst, to replenish fisheries, and to produce food and energy.

The warm summer months are characterised by the rapid warming of the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal as well as the southern tropical Indian Ocean. The winds begin to turn around from a land-to-ocean direction during winter to an ocean-to-land direction as summer commences.

The scorching heat on the subcontinent also comes with the threat of pre-monsoon cyclones. The North Indian Ocean doesn’t generate as many cyclones as the Pacific or the Atlantic Oceans, but the numbers and their rapid intensification have been growing ominously. The relatively small North Indian Ocean ensures cyclones don’t grow into the sort of hot powerhouses hurricanes and typhoons can be. But also the developing countries along the rim of South Asia, East Africa, and West Asia are sitting ducks in their path. Thus, cyclones tend to be the deadliest storms by mortality.

The warm ocean supports fisheries, big and small, and fish such as anchovies, mackerel, sardines, and tuna. Dolphins are a tourist attraction; some whales have also been sighted in the Arabian Sea. Tourists also flock to popular beaches and the corals from Lakshadweep to the Andaman-Nicobar Islands, all the way down to Reunion Island off Madagascar.

A unique configuration

The northern boundary of the Indian Ocean is closed off by the Asian landmass, minus tiny connections to the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea.

The southern Indian Ocean is also different from the other oceans thanks to two oceanic tunnels that connect it to the Pacific and the Southern Oceans.

Through the first tunnel — the Indonesian seas — the Pacific Ocean dumps up to 20 million cubic metres of water every second into the eastern Indian Ocean. These waters also transport a substantial amount of heat. They stay mostly in the top 500 m and move through the Indian Ocean towards Madagascar. The Pacific waters, called the Indonesian Throughflow, wander around the Indian Ocean and affect the circulation, temperature, and salinities.

The other tunnel connects the Indian Ocean to the Southern Ocean with two-way traffic. Colder, saltier and thus heavier waters flow into the Indian Ocean from the Southern Ocean below a depth of about 1 km. Due to the closed northern boundary, the waters slowly mix upward, and with the waters coming from the Pacific. The waters in the top 1 km eventually exit to the south.

The mix of heat and water masses in the Indian Ocean confer some mighty abilities to affect the uptake of heat in the world’s oceans.

The little ocean that could

The Indian Ocean is a warm bathtub despite the underwater tunnels because it is heavily influenced by the Pacific Ocean through an atmospheric bridge as well. The atmospheric circulation, dominated by a massive centre of rainfall over the Maritime Continent, creates mostly sinking air over the Indian Ocean. The atmosphere also warms the Indian Ocean year after year.

The Indian Ocean thus gains heat that it must get rid of via the waters moving south. With global warming, the Pacific has been dumping some additional heat in the Indian Ocean. The cold water coming in from the Southern Ocean is also not as cold as before.

The net result: the Indian Ocean is among the fastest warming oceans, with dire consequences for heat waves and extreme rain over the Indian subcontinent. Marine heat waves are also a major concern now for corals and fisheries.

The warming Indian Ocean is affecting the wind circulation in a way that’s also affecting the amount of heat the Pacific is able to take up. The Pacific Ocean takes up heat in its cold, eastern tropical region, and this is crucial to determine the rate of global warming. The Indian Ocean is thus playing a role in how well the Pacific can control global warming.

The other region where the ocean can draw down the heat and lock it away in deeper waters is in the North Atlantic. This is where surface waters become so dense that they sink like a rock into the depths. If the sinking of the water slows due to global warming — which seems to be the case — the heat doesn’t sink away from the surface as quickly as it used to.

Indeed, researchers have found that the Indian Ocean’s warming is actually helping accelerate the sinking of the heat, thus modulating global warming directly!

This is why, despite being the smallest tropical ocean, the Indian Ocean’s influence has become impossible to understate. Recall that the oceans take up over 90% of the additional heat more greenhouse gases in the atmosphere are trapping.

A hand in human evolution

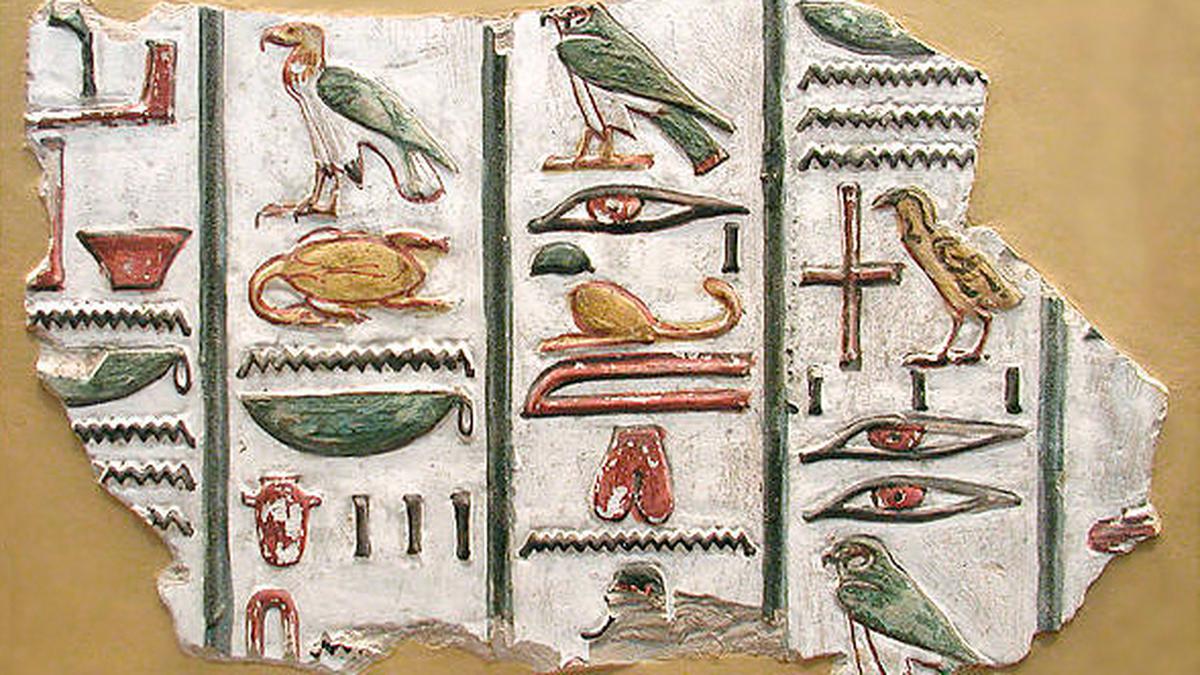

If this isn’t wondrous enough, the reconfiguration of the Indian Ocean may have played a role in the evolution of our ancestors as well.

Until about three million years ago, Australia and New Guinea were well south of the equator and the Indian Ocean was directly connected to the Pacific Ocean. And this Indo-Pacific Ocean was in a warm state known as a ‘permanent El Niño’ — a state that was associated with permanently plentiful rain and lush green forests over East Africa. Today, this part of Africa is arid.

The northward drift of Australia and New Guinea, which is still ongoing, separated the Indian and the Pacific Oceans around three million years ago. As a result, the eastern Pacific Ocean became cooler and the El Niño went from a permanent state to an episodic one, like the ones we’ve been seeing.

This transition aridified East Africa, turning its rainforests into grasslands and savannahs. Researchers have also hypothesised that these changes forced our ancestors, such as chimpanzees and gorillas, to move farther and run faster. In the rainforests, they had an abundance of food and hiding places and didn’t have to.

If these hypotheses are borne out, it’s possible the transformation also had a hand in the birth of bipedal movement — the ability to walk on two legs — which is much more efficient than moving on all four across larger distances.

The storied history of our neighbourhood ocean is thus a worthy thing to celebrate — and study — on World Oceans Day.

The author is a professor, IIT Bombay, and emeritus professor, University of Maryland.