Nine musicians dressed in bright outfits assemble on stage at the centre of an accordion museum in Yining city in Xinjiang province, China. It is June 17, the day of Eid-Ul-Adha, and everyone is in celebratory mood. Thousands of tourists and locals have gathered on Liuxing street despite the heat to enjoy street food, watch graceful performances, and drink chilled fresh juice and beer.

In the museum crammed with instruments, each musician holds an accordion. Before bursting into song, they introduce themselves, not by name but by ethnicity – Uyghur, Kazhak, Mongolian, Uzbek, and so on. Then, in chorus, they shout cheerfully in English, “We are all part of the Chinese nation.”

The proclamation of national unity and the carefully curated diversity on stage, particularly on the occasion of Eid, is significant. Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, located in northwestern China, is home to 56 ethnic groups, including the Uyghur, Kazakh, Mongol, Manchu, Uzbek, Xibe, and Russian, who are all termed “ethnic minorities” by the state. The vast province is home to followers of many religions such as Islam, Taoism, Buddhism, and Christianity.

For years, China has faced accusations from human rights groups of committing crimes against humanity of mostly Muslim ethnic groups in the region. According to several reports, including by the United Nations Human Rights Office, and Human Rights Watch, the Chinese were detaining Uyghurs, who form the majority of the ethnic minorities, in “detention centres” and subjecting them to abuse.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has rubbished these claims. It has repeatedly argued that these are not “detention centres” but “education and vocational training centres”. A booklet issued by the State Council Information Office says these centres were established with the “goal of educating and rehabilitating people guilty of minor crimes or law-breaking, and eradicating the influence of terrorism and extremism.” In 2019, however, the Chairman of the Xinjiang regional government announced that these centres would be gradually wound down “if society no longer needed them.”

Various studies have also claimed that the population of the Han Chinese, the country’s dominant ethnic group, has grown in the region, while the Uyghur population has declined ever since the People’s Republic of China took over the province in 1949.

However, official data show that the Uyghur population, which was 3.6 million in the first national population census of 1953, grew to 11.6 million (222%) in the seventh census of 2020. The increase has been attributed in part to the fact that Uyghurs and other minorities, along with the rural population, were exempt from China’s decades-old one-child policy.

The ‘Sinicisation’ of religion

At the Shaanxi mosque, an important heritage site in Yining, the Imam, Ma Jirong, says all these accusations are “greatly exaggerated”. He points towards the mosque, where 1,300 Muslims had assembled to pray that morning. “Since you are here, you can see for yourself,” he says. “Foreign countries have a hatred towards China. It is like a tumour in their body.”

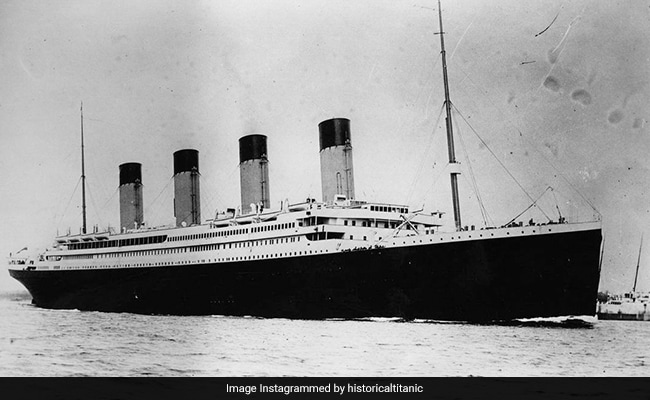

The centuries-old mosque behind him, painted in red and dark blue, is built in the “traditional palace style of Chinese architecture,” according to the guide. The structure is made of wood and brick and showcases the characteristically Chinese upturned eaves. The dome and minarets, commonly found in several mosques around the world, are missing. The call to prayer can be heard only within the premises. The ceiling is painted with flowers and plants, and journalists from West Asia wonder loudly about the absence of Arabic script on the inside walls.

The Shaanxi mosque in Yining, which is is built in the traditional palace style of Chinese architecture.

| Photo Credit:

Radhika Santhanam

Ma shrugs off these observations. “It is a Chinese mosque,” he says. “Mongolian, Uyghur, and many other ethnic communities participated in its construction. It shows that Xinjiang is an inseparable part of Chinese territory.”

This adaptation of religion to Chinese characteristics, and specifically to Chinese socialism, is what Abud Rakev Tumunyaz, the Imam at the Xinjiang Islamic Institute at Kuqa, 280 kilometres away, refers to as “Sinicisation”.

“Religion has no national boundaries, but believers have a motherland. Chinese people belong to the People’s Republic of China, so religion should adapt to socialism in China,” Tumunyaz, 62, contends.

Ma believes there is no contradiction between Chinese socialism and Islam. “Both prioritise the happiness of the people,” he says.

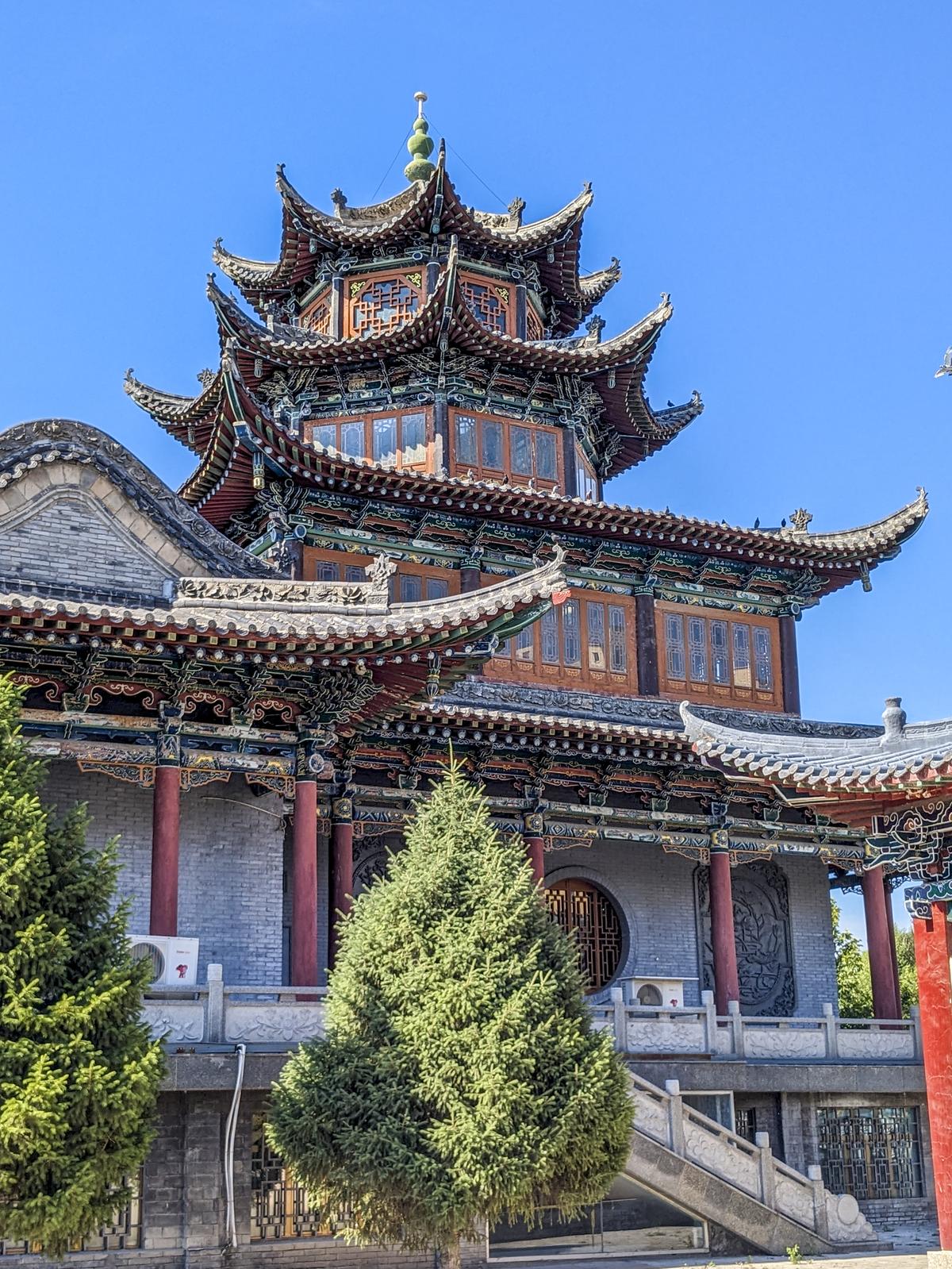

The mosque at Kuqa has a dome and minarets. Inside the Islamic Institute’s sprawling library, which houses about 30,000 books, the Imam flips through the copies of the Koran laid neatly on a table. The bound books look new and the pages crackle when flipped. There are copies in Uyghur, Arabic, and Chinese. Newspapers in Mongolian, Uyghur, and other languages are stacked in a rack in the reading area.

The mosque at the Xinjiang Islamic Institute of Kuqa.

| Photo Credit:

Radhika Santhanam

However, just like the rest of the country, Xinjiang promotes standard Chinese in public educational institutions; students say lessons are not taught in Uyghur or other languages. Uyghur is spoken everywhere, but shop signs are mostly only in Chinese.

A government booklet claims that ethnic minorities are “enthusiastic” about learning and using standard Chinese. It says ethnic groups are “encouraged to learn spoken and written languages from each other… (emphasis added)” and ethnic languages are “extensively used in areas such as judicature, administration, education, press and publishing, radio and television…”

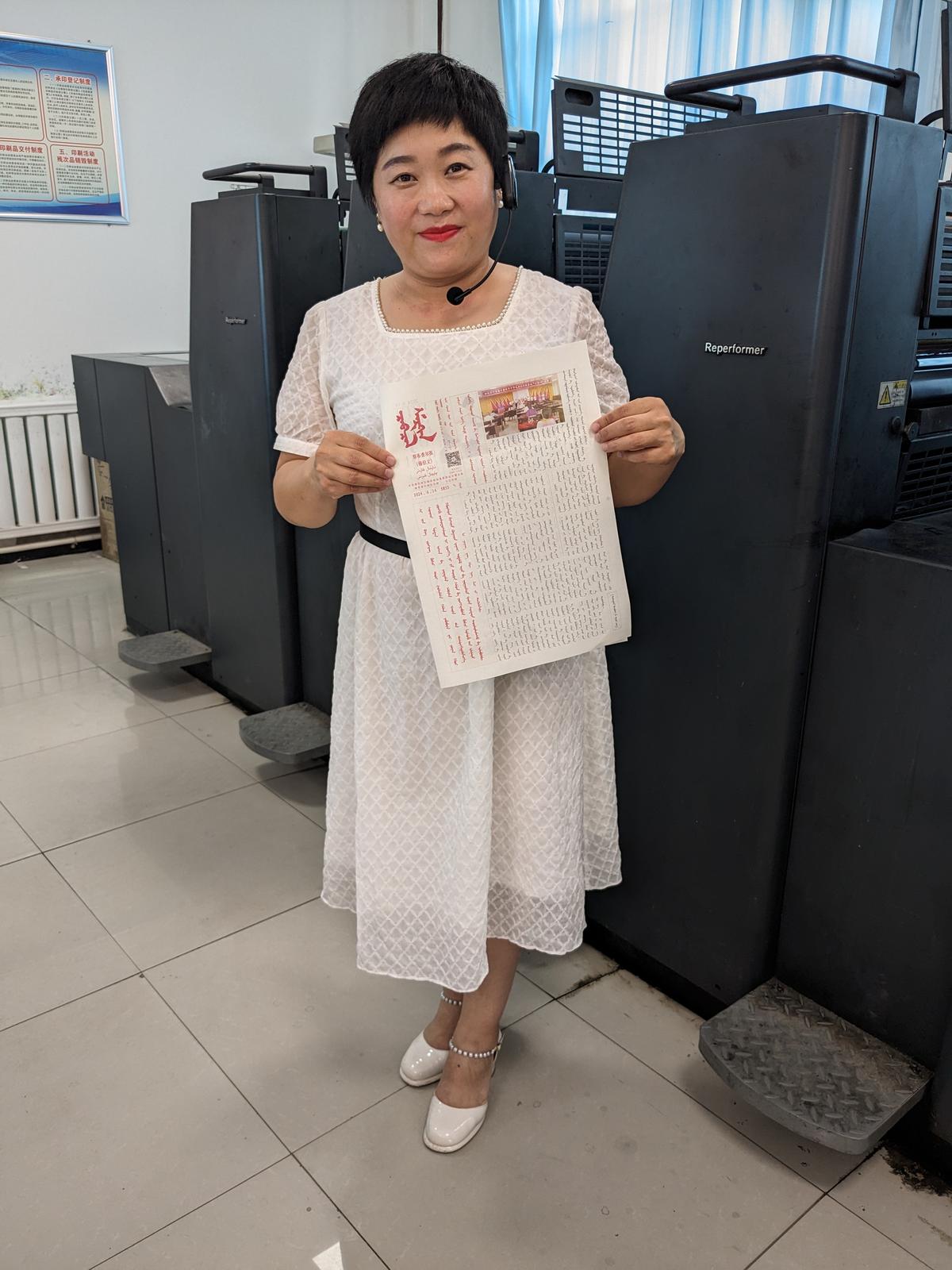

A small newsroom and the printing press of a county-level newspaper called Chabuchar Daily, brought out in the Xibo or Xibe language, are showcased as evidence of this. The four-page tabloid, which translates newspaper reports into Xibo, which is closely related to Manchu, a nearly extinct language, is brought out twice a week for the 30,000 speakers of Xibo in Xinjiang. “As you can see, the government cares about ethnic cultures and languages,” says one of the editors, Zhao Jinxiu.

Zhao Jinxiu, one of the editors of the Chabuchar Daily tabloid, which is published in the Xibe language.

| Photo Credit:

Radhika Santhanam

Deradicalisation programme

Both Ma and Tumunyaz emphasise the importance of “laws and regulations” and firmly state that Islam should “develop accordingly”. When asked to cite an example of how the law dictates the practice of religion, Tumunyaz says, “The government designates areas where prayers and other religious activities can take place.”

At the Islamic Institute at Kuqa, students are given religious education, which includes learning to recite the Koran. They are taught Chinese culture and history, and Islamic history from the time it was introduced in China about 1,300 years ago. They study lessons about the civil code, and laws and regulations regarding religion. They also undergo a ‘deradicalisation programme’.

The Chinese argue that this stems from Xinjiang’s troubled history. In the last two decades, the region has seen many terror attacks. In 2012, knife-wielding terrorists attacked civilians in Kashgar, leaving 15 dead. In May 2014, attackers crashed cars into shoppers and threw explosives, killing more than 30 people in the capital city of Ürümqi. In July the same year, an Imam in Kashgar was stabbed to death. China has blamed the East Turkestan Islamic Movement, which was founded by militant Uyghur separatists, for some of these attacks.

The fight against what the government calls the “three evils of extremism, terrorism, and separatism” is also China’s rationale for the “education and vocational training centres.” In written communication with the media, the CCP says through these centres, Xinjiang has “destroyed 1,588 violent and terrorist gangs, arrested 12,995 terrorists…, punished 30,645 people for 4,858 illegal religious activities, and confiscated 3,45,229 copies of illegal religious materials” since 2014. The curriculum at the centres, it says, “begins with learning standard spoken and written Chinese language, then moves onto studying the law, and concludes with learning vocational skills”.

Waiting for freedom

However, several Uyghurs have publicly spoken and written about how they did not choose to go to these centres. Many critics have also raised questions about why prominent Uyghur intellectuals, writers, and artists were sent to places that purportedly provide “vocational skills”.

Many ethnic minorities have also fled China fearing ill treatment at these centres. In 2013, three Uyghurs — Adil, Abdul Khaliq, and Salamu — from Kargilik in southwest Xinjiang crossed the border into Ladakh in India without any travel documents. They were apprehended by the Indian Army, which handed them over to the Indo-Tibetan Border Police. Later, the three of them were handed over to the local police. They have been in jail since.

“All the three young men, one of whom was a minor then, fled to India saying Uyghurs were being persecuted in their country,” says Mohammad Shafi Lassu, a lawyer in Leh who is representing them. “They said they had seen all kinds of atrocities. They came to India because they knew that Pakistan would hand them back to China. But in India, after completing their sentence, they were booked under the draconian Public Safety Act in 2015.” The Jammu and Kashmir Public Safety Act, 1978, is a preventive detention law under which a person is taken into custody so that they will not act in a manner that is prejudicial to “the security of the state or the maintenance of public order”.

Lassu sounds tired. “I have little hope for their future,” he says. Apart from the stringent law, he also cites India’s neutrality on the Uyghur question as a reason for his despair. In 2022, the country abstained on a draft resolution at the United Nations Human Rights Commission on holding a debate on human rights in Xinjiang, arguing that it “favours a dialogue to deal with these issues” instead.

It is common refrain in China that “international forces were influencing people over the web”; this is why the government also further tightened its control over the Internet, a move defended as ‘cyber sovereignty’. Confident now that terrorism is a thing of the past, Xinjiang also has an ‘exhibition of anti-terrorism and anti-extremism’.

The fear of attack had turned Xinjiang into a security zone by all accounts. This seems to have mostly dissipated, except in parts such as the International Grand Bazaar in Ürümqi, where men in uniform check foreigners’ passports at the entrance and a security van with armed men is permanently stationed outside.

Tumunyaz says “religion is not extremism and vice versa”; yet displays of overt religiosity are clearly frowned upon and could land people in prison. “The deradicalisation programme is not about targeting any religion or ethnic minority,” he says. “We will strike down any separatist.”

Tumunyaz, who is also the president of the Xinjiang Islamic Institute and vice chairman of the Chinese Islamic Association, is expecting two more delegations in the afternoon. He says delegates from the United Nations visited him last week. He appears to be the designated point person in Kuqa for all Islam-related questions.

Thrust on development

The message that the nation comes first, before ethnicity and religion, is assertive also given Xinjiang’s strategic location. The province borders Mongolia, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, and India. As a consequence, it is of great importance to China’s mammoth Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which facilitates trade and commerce across the ancient Silk Road routes that connected Asia, West Asia, and Europe for about 1,500 years, from the beginning of the Han dynasty in 130 BCE. Xinjiang was an important section of the ancient Silk Road, which is why the province, characterised by three mountains and two basins, is now called the core area of the Silk Road economic belt.

This has always been one of China’s poorest regions, but the thrust on development is clear to the eye. Ürümqi, Yining, and Kuqa all boast excellent infrastructure, delivered with what the guide calls “Chinese efficiency”. There are wide roads with cycling and walking paths lined with trees. Industries including textiles, power, manufacturing, and petrochemicals have sprung up everywhere. Xinjiang’s GDP rose from about $167.2 billion in 2017 to $278.4 billion in 2022.

In Kuqa Qiuz Alley, a sprawling old Uyghur home, whose residents have long since moved out, has been converted into an area for tourists to experience Uyghur culture.

| Photo Credit:

Radhika Santhanam

Being central to the BRI has also meant that Xinjiang now generates significant revenue from tourism ($14.1 billion in 2022). In Jiayi village in Xinhe county in Yining, tourists flock to an exhibition centre of musical instruments, which is presented as ‘intangible cultural heritage’. In Kuqa Qiuz Alley, a sprawling old Uyghur home, whose residents have long since moved out, has been converted into an area for tourists to “experience Uyghur culture”. The Grand Bazaar contains a museum of giant naans, and shops selling Uyghur caps and outfits made of Atlas silk. Professor James Leibold at La Trobe University, Melbourne, who is an expert on the politics of ethnicity and race in China, refers to this as “museum-style multiculturalism”, while the Chinese in Xinjiang are at pains to point out how this is in fact “protection of ethnic minority culture”.

Everywhere journalists are taken, there is an emphasis on how ethnic groups are part of the BRI. At the assembly workshop of the Automobile Guangzhou Car Motor Company, where staff and robots work together, the General Manager, Luo Haitian, says, “Our staff is diversified; about 20% of them are ethnic groups.”

An assembly workshop of the Guangzhou Atutomobile Group Co Ltd, Xinjiang. The province is crucial to China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

| Photo Credit:

Radhika Santhanam

At the Xinjiang Software Park, established in 2015, Yang Qing, director of the department of communications, says, “The development of this park is part of our strategic plan to develop five hubs in the economic belt of Xinjiang. Our goal is to be a carrier of the Digital Silk Road. We provide technical support for the stability of society of Xinjiang and for high-quality economic development.”

Yang points to various products and applications that have made both the daily lives of the people as well as surveillance by the state and the people — of traffic, grazing cattle, movement, etc. — easier.

Her point on high-quality economic development is borne out by data. But how does technical support ensure stability? “This region was once influenced by terrorism,” Yang explains. “So now, we monitor everything.”

The writer travelled to Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region as part of a delegation of international journalists from 16 countries hosted by the State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China