Neurotechnologies have come a long way since the development of electroencephalography (EEG). Invented a hundred years ago, the EEG has had a significant impact on our knowledge of the human brain and various treatments of brain disorders. Many researchers expect that soon there will be wearable EEGs that could directly assist human cognitive functions. Elon Musk’s Neuralink has also kindled hope about using brain-computer links to help physically impaired people restore some lost function.

The 1990s was popularly known as the ‘decade of the brain’ as research on neuroscience and neurotechnologies received a big boost from various governments. The European Union’s ‘Human Brain Project’ and the subsequent ‘BRAIN’ initiative were some of the major initiatives. Today, research in these areas is also supported by private companies, especially in the life sciences sector, and is also more extensive than before, including brain pathophysiology, deep-brain stimulation, and neuromarketing.

Neurotechnologies range from the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) that health workers routinely use to the rarer brain-computer interfaces (BCI). In the last few decades, the type of sensory information these technologies have become able to record has expanded considerably. Sophisticated biosensors that can record a person’s physiological activities, behavioural responses, and emotions are no longer fiction.

How is neurodata valuable?

The digitisation of neuro-data raises great opportunities as well as concerns. Not all neurotech users are care-seekers, as smartwatches, apps, and ‘embeddables’ are integrated more into day-to-day activities. After users’ devices collect these data, there will be an option to transmit them to healthcare providers and private companies, who will have an incentive to integrate them in a larger knowledge framework to offer, say, real-time tracking of health indicators and personalised suggestions.

This also increases the risk of surveillance — from multiple sources for different purposes. For example, a manager can monitor the movements and mental states of an employee to track alertness, fatigue, and other indicators. This data can be shared with various state and non-state actors, including other employers and physicians. This can be a boon but can also help these actors exert more control over individuals’ behaviour. Digitised health data also has great commercial value in advertising and marketing (including neuromarketing).

Surging investment by the private sector in neurotechnologies has also raised concerns about their governance and regulation. There are unique ethical concerns here because these neurotechnologies can probe individuals’ physiological and psychological states.

Ultimately the right to think freely and mental privacy can be imperilled. In the garb of performance monitoring and assessing efficiency, different entities may be able to track and monitor the movements and behaviour of diverse sections of the population, individually and collectively.

What is neuroethics?

The right to think freely and the right to safeguard one’s mental statuses and thoughts from surveillance and monitoring are precious fundamental rights but technological advancements may cheapen them in some contexts. Experts strive to adopt ethical standards such that humankind benefits most from the use of neurotechnologies while minimising harm.

This is the principal concern of neuroethics. It has emerged as an important field of research and action in the last two decades.

Various institutions and funding agencies have tried to identify and enforce ethical principles for neuro-X research and development. In 2015, the U.S. Presidential Commission on Bioethics published a two-volume report entitled ‘Gray Matters’. It focused its analysis on three “controversial topics that illustrate the ethical tensions and societal implications of advancing neuroscience and technology: cognitive enhancement, consent capacity, and neuroscience and the legal system”.

In 2019, the OECD recommended nine principles to ensure the ethical development and use of neurotechnologies based on the concept of responsible innovation. Two of them were “safeguarding personal brain data” and “anticipating and monitoring potential unintended use and/or misuse”.

UNESCO published a paper in 2022 in which it said: “As [neurotech] actively interacts with, and alters the human brain, this technology also raises issues of human identity, freedom of thought, autonomy, privacy and flourishing. The risk of unauthorised access to the sensitive information stored in the brain is a case in point. Already today, neural data is increasingly sought after for commercial purposes, such as digital phenotyping, emotional information, neurogaming and neuromarketing. Neuromarketing units have been developed by industry to evaluate, and even alter consumer preferences — raising serious concerns about mental privacy. These risks can also pose serious problems when dealing with non-democratic governments.”

In 2023, researchers at the Institute of Neuroethics in Atlanta in the U.S. reviewed several guideline documents and ethical frameworks published by institutions, think-tanks, governments, etc. worldwide. Among other things, they wrote, these texts ask researchers to “proactively consider and communicate potential implications of scientific advances” and “to improve and meaningfully incorporate ethics in training and the conduct of research”.

What are your neurorights?

Internationally accepted human rights principles and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights provide some inkling as to individuals’ neurorights. But the extent to which they are enforceable depends on the laws in each jurisdiction.

In 2021, Chile became the first country to legally recognise its citizens’ neurorights when its Senate agreed to amend the constitution. As a result, according to a 2022 article in the journal AI & Society, technological developments in the country must “respect people’s physical and mental integrity” and its laws should “protect brain activity and information related to it”. In the U.S., Colorado enacted a law in April 2024 to protect individuals’ neurological privacy while California is deliberating a similar instrument.

But some legal scholars have said the current rights framework is adequate and that laws specific to neurorights may be limited in scope. For example, in a paper published last year in the journal AJOB Neuroscience, Pennsylvania State University scholars discussed whether neuro-privacy is meaningfully separate from data privacy.

An important challenge to developing suitable neuroethical standards is that the underlying technologies are evolving rapidly. The contexts in which people use these technologies are also diverse, beset by disparate expectations and cultural norms. For now, UNESCO has appointed an expert group to develop the “first global framework on the ethics of neurotechnology”, expected to be adopted by the end of 2025. While this framework is not likely to result in a treaty or a binding convention, it could have a major impact on governments’ guidance documents and policy narratives.

Apart from UNESCO, various intergovernmental organisations are also actively working on the human rights dimension of neurotechnologies.

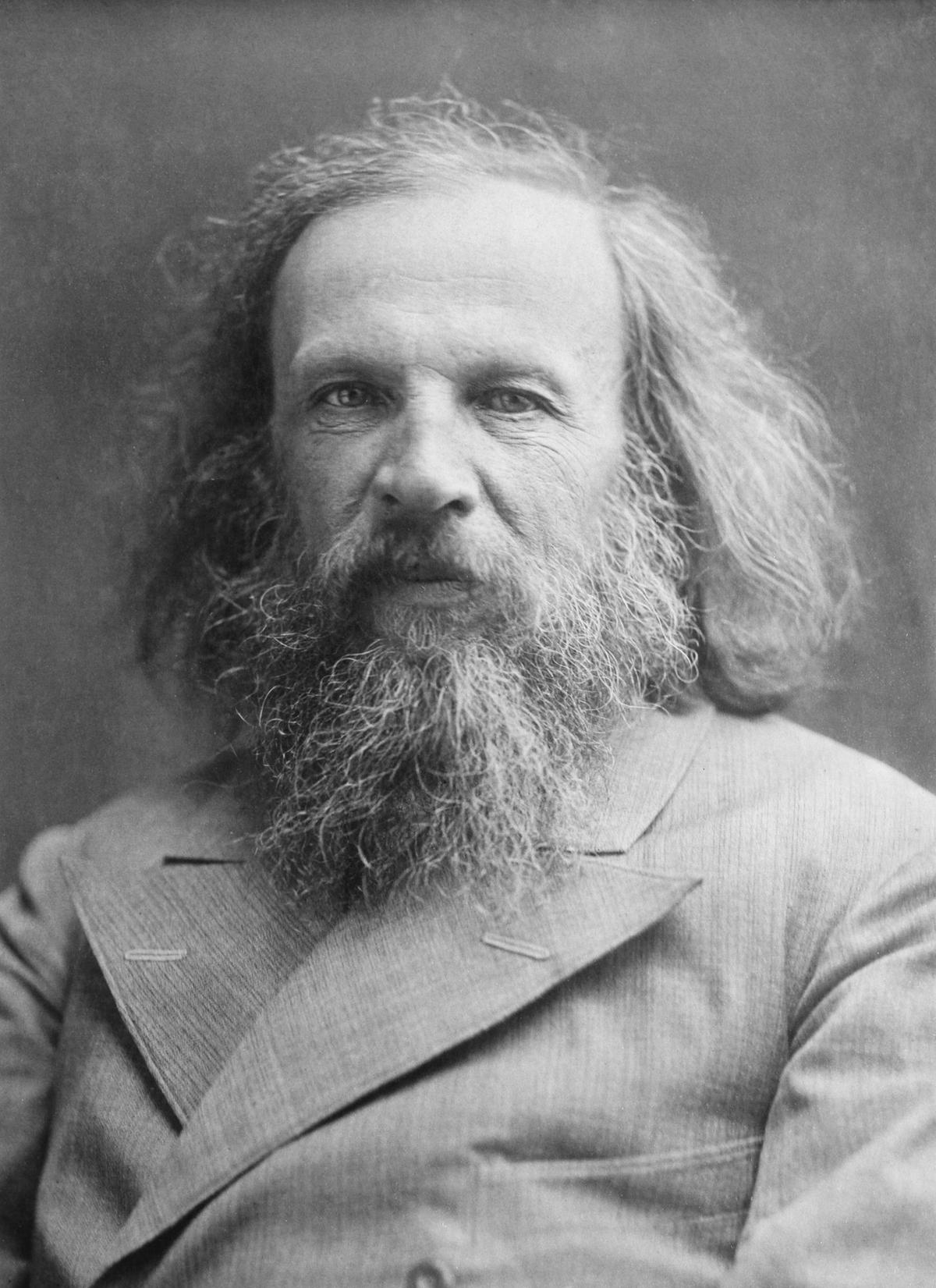

Krishna Ravi Srinivas is adjunct professor of law, NALSAR University of Law Hyderabad; consultant, RIS, New Delhi; and associate faculty fellow, CeRAI, IIT Madras.