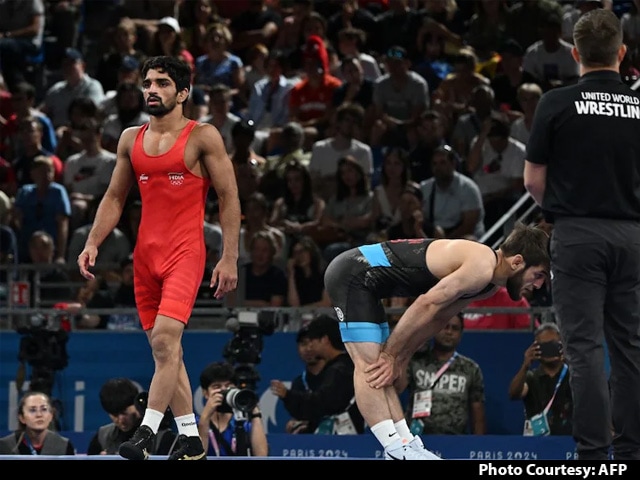

Protestors arrested as they marched to commemorate the 1st month anniversary of the June 25 shootings during demonstrations against government proposed tax hikes in Nairobi on July 25, 2024.

| Photo Credit: AFP

The story so far: On June 25, protests turned violent in Kenya when lawmakers passed a controversial financial Bill. Although President William Ruto withdrew the Bill the next day, protests continued. According to the Kenya National Human Rights Commission (KNHRC), over 50 people have been killed and 628 were arrested in the violence.

What did the Bill entail?

The Bill was introduced in May and imposed a 16% Value-Added Tax (VAT) on bread, 25% excise duty on cooking oil, 5% tax on digital monetary transactions, an annual 2.5% tax on vehicles, an eco-tax on plastic goods, a 16% tax on goods and services for the construction and equipping of specialised hospitals and an increase in import tax from two to three per cent. The government dropped a few of them after the initial round of protests. The state’s larger objective is to collect $2.7 billion in taxes to pay off the debt of $80 billion, which is 68% of Kenya’s GDP. The Bill caused public distress due to the increasing cost of living.

Why are protests continuing?

Mr. Ruto withdrew the controversial Bill on June 26 following country-wide violent protests, and when his use of force and the death of the protesters drew global criticism. The protest has since then expanded on its causes, demands, geography and intensity.

The protests were an expression of long-standing discontent over Mr. Ruto’s administration and financial management. For example, a month after coming to power, Mr. Ruto scrapped fuel subsidies. The July 2023 protests against another Bill, which introduced a 5% housing levy and a 16% tax on petroleum products, killed 23 people. And thus, the initial intentions behind the protests diverted after the President withdrew the Bill as the use of force, live ammunition and deaths angered the protesters. The second phase of protests was against police brutality. By the third week, it had evolved into anti-government protests over unaddressed public grievances, corruption, mis-governance, and a demand for Mr. Ruto’s resignation.

Moreover, the immediate success of the protests encouraged Kenyans to join the masses against all public grievances. Mr. Ruto came to power in September 2022 promising to address unemployment and poverty. However, he failed to maintain the popularity he received during the elections. The trading economics website recorded Kenya’s inflation rate at 5.1% in May. The World Bank reported that although Kenya is one of the most developing countries in Africa, a third of its 52 million people live in poverty and that 5.7% of the labour force is unemployed, which is the highest in East Africa.

According to Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index 2023, Kenya ranks 126 out of 180.

What next?

Mr. Ruto sacked his cabinet and announced a new one on July 19. While the inclusion of four opposition figures into the cabinet might hold the opposition party from joining the protests, it is less likely to slow down the protests. While the country plunges into a debt crisis, any further financial reforms in the near future would trigger a similar response, implying that Mr. Ruto’s administration is in crisis.

Several other African countries are also vulnerable to similar instabilities due to the debt crisis. According to the World Bank, nine African countries face a debt crisis in 2024, and 15 among them are at risk of distress. They depend on regular borrowing, doubling the total debt. The debt burden often forces the governments to either increase the taxes or wait for a debt reconstruction.

However, the Kenyan protests have influenced the African youth and their potential to mobilise the masses. Ugandan youth have followed Kenya, protesting against corruption on July 23. Several other illiberal democracies in Africa are likely to follow Kenya and Uganda. Chosen the same method, protests would trigger violence across the region.

The author is a Research Associate with Africa Studies at the National Institute of Advanced Studies, Bengaluru.