Sport is primarily seen as the finest distillation of life’s exuberance. Moving limbs, kinetic energy, streaks of sweat, the earnest desire to win — above all, it is in essence the pursuit of happiness. Precisely due to these associations, even if they are not explicitly spelt out, an athlete’s death often seems like an oxymoron to our startled minds.

How can a sportsperson die? Yes, that old line about death and taxes being inevitable remains strong as ever, and all of us are conscious about mortality. Yet, when the newswires bring home that sombre news about a player’s demise, be it current or former, be it on the field, in a hospital bed, through an accident or self-inflicted harm, how does the larger public react?

Why acceptance isn’t easy

The usual grief-template of ‘shock, denial and grudging acceptance’ doesn’t necessarily work. Obviously shock and denial remain massive but the acceptance part takes an inordinately long time. How can this wonderful athlete, who did spectacular things on the field, suddenly turn lifeless? This train of thought is at a dissonance with the fine print of most sports: injuries can happen and some could be life-threatening.

Over the last few weeks, life’s full-stop was evident in the sporting arena. Former India opener Aunshuman Gaekwad lost his battle against cancer at 71. And as if death was stalking the cricketing fields, England’s middle-order stalwart of the 1990s and early 2000s, Graham Thorpe too succumbed at 55. It has now come to light through his grieving family that the left-hander’s demise was a case of death by suicide.

Since sport is also invested with the metaphor of being in a battlefield, the presumption is that a sportsperson would even pause Father Time. Eternity and utopia are themes running through any athletic endeavour, and they get juxtaposed with the sporting practitioner’s life.

If Gaekwad could survive the bloodbath at Sabina Park in 1976, couldn’t he muster the will to overcome cancer? Thorpe was at his resilient best against the finest of attacks and yet his mind’s undercurrents, dallying with the diabolical shadows of self-doubt and depression, left him spent. Denial was again at play in the way we reacted and it is surely not the first time.

Undying love: Ayrton Senna continues to be worshipped by racing fans three decades after his death. | Photo credit: Getty Images

An Ayrton Senna departing in a crash on an F1 track at Bologna in Italy in 1994 still rankles. Senna was the master of mechanical speed but what was this haste towards the exit door? His legacy stands but his death at a mere 34 again drags in those queries about ‘what could have been?’

It is a question that shadows former India opener Raman Lamba too. Struck on the head while fielding close-in during a game at Dhaka, the Delhiite never recovered. A man, who once smashed the visiting Aussies all over the park during an ODI series, now lay dead. This was in 1998, and again, while being fully aware of the harm that a cricketing red cherry can inflict, disbelief hung in the air like a dark shroud.

Silence, tears, denial

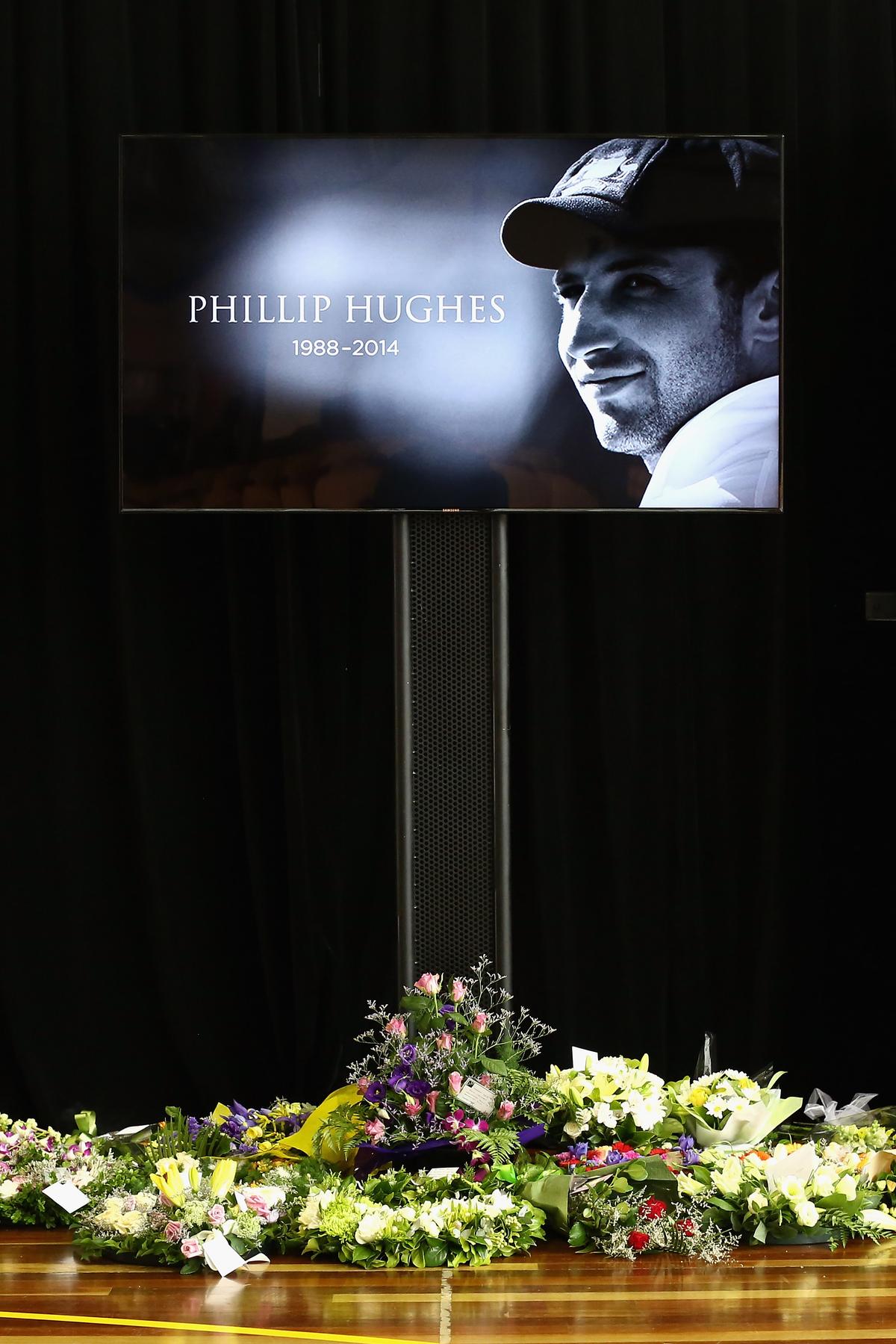

Death on the grass is a dastardly episode that finds repeated segments as some footballers have inexplicably moved on while pursuing the beautiful game. The autopsy report about injuries and cardiac-arrest never cuts ice even if it is the essential truth. Australian opener Phillip Hughes pinned down forever by a bouncer in 2014 evoked the same response: silence, tears and denial.

Sport at its highest form is always the truth. What you see is real, be it triumph or defeat, laughter or angst. But death, the one reality associated with life, is almost deemed impossible in the realm of sport. A tent-pegger in equestrian may find his horse swerving into the woods leaving him hung upon a branch with grievous injuries. Still in those rare cases, the abiding reflexive thought is ‘how could that happen?’

But sport is a workspace in which its practitioners are not essentially in control. A Hughes or a Lamba can never tone down the danger residing within a cricket ball. The former wore a helmet, the latter did not, and still their fate was the same. The metaphysical poet John Donne wrote through his poem Death, be not proud: “One short sleep past, we wake eternally. And death shall be no more: Death, thou shalt die.”

A wordsmith with a feverish imagination, a rebellious streak and a philosophical air may write these lines but even Donne became part of the sands of time in 1631. Be it life or its athletic exposition sport, death is the unwelcome guest hanging around at the blind corner. It always seems difficult to accept the finish-line when the breath ebbs, rigor mortis steps in and the much speculated 21-gram loss in weight supposedly happens, as physician Duncan MacDougall propagated in 1907.

Gone too soon: The tragic demise of Australian opener Phillip Hughes was another reminder that sport is a workspace in which its practitioners are not in control. | Photo credit: Getty Images

Sporting gods like Diego Maradona, Pele, Muhammad Ali, Shane Warne or Milkha Singh, all evoke strong emotions rippling through a fandom that seeks a quick-fix for a collective self-esteem enhancement. When a star wins, the ordinary fan’s spirit soars. By extension, the athlete dispensing confidence to the larger mass could be seen as a mass-hypnosis state which perhaps the subject is never conscious about. This near-religious or cult-propagating experience tends to cloud the fans’ judgement.

That the sportsperson can never fail at the micro level and never die at the macro space becomes an idea that seeps in like a steady monsoon rain. An amalgam of fondness, love and reverence creeps in and inevitably the ‘acceptance phase’ of an athlete’s death becomes prolonged. It is almost as if we lost a near and dear one.

The athlete’s reality

Still for the athlete the pressure is real. Most deal with life-long scars. Wicketkeepers have gnarled fingers, footballers end up with busted knees and ankles. The fear of failure, lonely nights in hotel rooms, all take a toll. Like army veterans, the retired player harks back to the good old days. The audience, after a while, gets bored. Relief is then excessively sought through a glass brimming with spirits.

For every Martina Navratilova or Yuvraj Singh surviving cancer, there are others who find the mountain too steep to climb. High on their own sense of invincibility, because the indomitable belief drives them forward, athletes tend to ignore health’s alarm bells. Some recover in time, others struggle. Still the larger population tends to lean on the sportsperson’s visible fitness and never get a grip on a silent illness or the shards of pain scything through the mind.

Ironically, death as a metaphor lurks around sport. A dismissal, a goal missed, a catch dropped, even a celebrated retirement after a storied career are all seen as mini-deaths. But when the final whistle is genuinely blown in life, the athlete’s fandom would rather block that news for a while. If sport is life, can death be far behind?

Assistance for overcoming suicidal thoughts is available on the State’s health helpline 104, Tele-MANAS 14416 and Sneha’s suicide prevention helpline 044-24640050. Helplines across the country can be accessed here: https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/suicide-prevention-helplines/article61753129.ece