After what seems like an eternity – perhaps that’s because it really is – some of the biggest active names in Indian cricket will assemble under one umbrella to ply their wares in domestic cricket. That shouldn’t be news in itself, but if it is, it’s because of the short shrift the domestic game has increasingly been receiving from those that have graduated beyond that level and have gone on to represent the country.

This year’s Duleep Trophy, or at least its first round, to be specific, will witness many of the big boys in action for the four teams picked by the national selectors ahead of the international home season, beginning in Chennai on September 19. India will host Bangladesh for two Tests, and three Twenty20 Internationals, before taking on New Zealand in three further Tests, after which they will emplane for Australia for their first five-Test showdown Down Under since 1991-92.

India’s last Test match was in Dharamshala against England, in the first week of March. Since then, there has been a steady diet of T20 cricket — the IPL, the T20 World Cup, a five-match tour of Zimbabwe, and three games in Sri Lanka — that only ended with the three-match One-Day International series which the Indians surrendered to the Lankans 0-2 earlier this month.

As such, the first round of the Duleep Trophy, scheduled to begin on September 5, offers those certain to be in the Test squad and those aspiring to break in, or break back in, their only meaningful red-ball, first-class competitive outing before the first Test against Bangladesh. Some of the players are already on their way to fine-tuning their games at the ongoing Buchi Babu Trophy tournament in Tamil Nadu, but there is nothing like a First Class game to get the red-ball juices flowing all over again.

Notable absentees

The notable absentees from the Duleep Trophy are Test and ODI skipper Rohit Sharma, his predecessor Virat Kohli, pace spearhead Jasprit Bumrah and off-spinning great R. Ashwin. They are the exceptions to the rule; in recent times, the Board of Control for Cricket in India has read the riot act, making it mandatory for those available to play at the domestic level. Things shouldn’t have come to such a pass, but with players tending to prioritise international and franchise cricket at the expense of turning out for their respective states, the governing body had no option but to step in. The omission from the list of centrally contracted players of Shreyas Iyer and Ishan Kishan for failing to play for Mumbai and Jharkhand respectively in the Ranji Trophy was the clearest indication that dereliction of duty would come at a price.

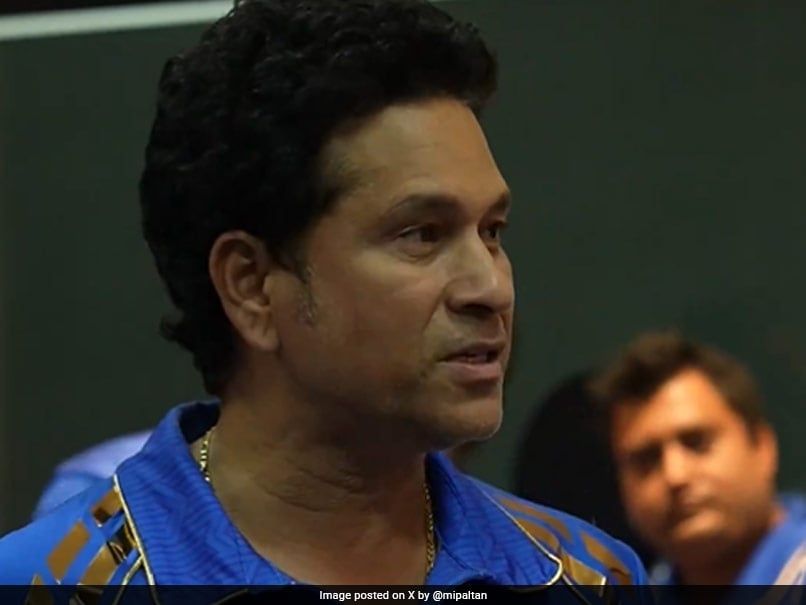

It wasn’t always like this, you know. Even till the early 2000s, little was made of a Sachin Tendulkar practically stepping off an aircraft after an overseas tour to turn out in Mumbai colours, or a Rahul Dravid or an Anil Kumble doing likewise for Karnataka. It was from the not-so-green pastures of state vs state and zone vs zone face-offs that the route to the national team opened up. Players hardly thought they were doing their state a favour by representing it at every available opportunity. Because some of the most luminous stars were on show, fans too flocked to the grounds in large numbers. While it is fashionable now to decry the lack of spectator interest in the domestic game, maybe it really isn’t hard to see why the fans stay away. After all, if that’s what the players choose to do, who can really blame the audiences, short-changed as they are when it comes to basic facilities even at venues hosting international games?

Over the last few years, the only time some of the big boys have sporadically played in the Ranji Trophy is when they have been on the comeback trail, or when they have had to prove their match-readiness after an injury lay-off. Ashwin is one of the few honourable exceptions; he loves nothing more than playing a game of cricket, any game of cricket. For the rest, a return to the ‘drudgery’ of domestic cricket is a punishment of sorts. In private, many players have spoken of a lack of ‘motivation’ to play at a level lower than international cricket, but how motivation (or the lack of it) can even be a factor when one is representing the entity that facilitated an ascension to the higher echelons is hard to fathom.

Vice-versa

While it is true that the domestic game needs the superstars, it is equally true that the established names need the domestic experience, too. One of the reasons for a gradual decline in standards when it comes to playing even passable spin bowling on helpful tracks is because most of those that are regulars in Test cricket hardly encounter such pitches on a sustained basis and therefore their games against spin take a beating once they become even semi-permanent cogs in the Test set-up.

Within the landscape of the national team, there is greater emphasis on shoring up one’s technique against fast bowling, which is the staple diet that will confront the batters when they travel to England and Australia and South Africa and New Zealand. The faster, bouncier strips that will await the batters aren’t dime a dozen in India, so it becomes imperative that when they get together as the Indian team, they leave no stone unturned in their bid to prepare for the unfamiliar, demanding challenges that lie ahead. This is something Dravid, no less, had alluded to several years back; several Indian Test batters had to make a conscious effort to ensure they retained the muscle memory of batting against spin. Even though they played Anil Kumble and Harbhajan Singh in the nets, it wasn’t on less-than-good decks. There would be no pressure to score or survive, which can subconsciously trigger a loss of intensity and concentration. Despite all this, if Dravid and V.V.S. Laxman and Tendulkar and Virender Sehwag and current head coach Gautam Gambhir all played spin of the highest quality with consummate ease, it wasn’t definitely by accident.

Perhaps this Duleep Trophy game is just one match and therefore it might be presumptuous to label this as the beginning of a trend, but it can’t be overlooked that both BCCI secretary Jay Shah and Rohit, and Gambhir after taking over as head coach, have pledged their commitment to the domestic game. Increasingly, those not in the Test squad will therefore have to return to the ‘drudgery’ of state vs state showdowns and, if they have to, dig deep to discover the motivation that should come naturally, in any case. That will mean greater interest among fans, and perhaps better facilities too in terms of where the matches are played and what kinds of pitches are laid out. Currently, domestic cricket is dangerously close to falling into the ‘formality’ bracket, but it’s precisely this stage that has contributed to the vibrancy of Indian cricket now, and it must be treated with the respect and reverence that it deserves, not relegated to an afterthought as it has been for several seasons.

Perhaps, there is a case for the four players who have been exempted from the Duleep to also have rediscovered their red-ball mojo. Kohli has had a poor time of it in international cricket in 2024, with just a solitary half-century in 15 innings, his Player of the Final-winning 76 in the T20 World Cup in late June. In his only Test outing this year, he scored 46 and 12 on an admittedly terrible surface in Cape Town. That match ended on January 4 and Kohli didn’t play in the five-Test home series against England, away as he was on paternity leave; by the time of the first encounter against Bangladesh, eight and a half months would have elapsed since his previous Test outing. Especially considering that he averages 19.73 in 15 international knocks this year, it wouldn’t have been the worst idea for him to have a proper red-ball hit, no matter how experienced and accomplished he might be.

Rohit, Bumrah and Ashwin all played in the aforesaid Tests against England. Maybe they all needed a run out too, though like Kohli, since they will form the core of India’s challenge for much of a long season, the decision-makers felt in their collective wisdom that they were better off being physically well rested and mentally fresh. It’s not as if they have anything to prove – neither form nor fitness or commitment and passion – and so perhaps it’s in the fitness of things that those four slots go to younger players who will be thrilled at the opportunity to bowl at a Shubman Gill or an Yashasvi Jaiswal or face up to a Mohammed Siraj or a Kuldeep Yadav.

The first indication of what the presence of stars can do to domestic cricket is the shifting of one of the first-round matches to the M. Chinnaswamy Stadium in Bengaluru. It is more or less certain that the broadcasters had something to do with the move, but even so, it’s a win of sorts for a competition that has flown under the radar in recent times. Whether the fans will populate the stands is another matter altogether, but if batters, especially, play for their respective states around international cricket, it is certain to rejuvenate the sport at a level that is only a couple of rungs below the highest.