Excess body weight, especially abdominal obesity, is associated with several health problems like diabetes, high blood pressure, and cardiovascular disease. Various weight reduction methods have been tried over the years, most have not stood the test of time.

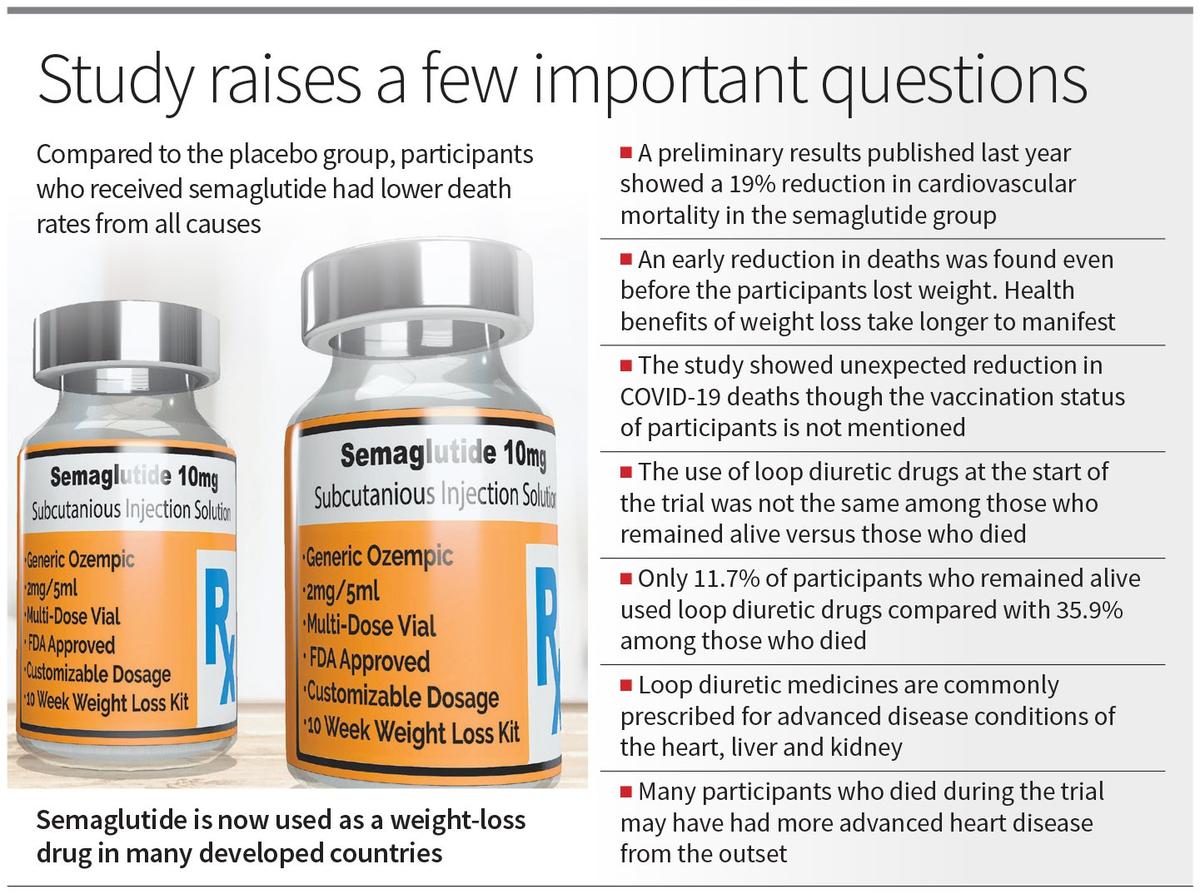

Recently, a class of drugs called GLP-1 agonists, originally used for diabetes, has gained attention for its role in weight loss. These drugs mimic the gut hormone GLP-1, which enhances insulin release and slows digestion, promoting a sense of fullness. Among these drugs, semaglutide has been in use for diabetes since 2017. In higher doses, it is now used as a weight-loss drug in Western countries. A study published recently in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology revealed promising results from its use in people without diabetes.

The SELECT trial, funded by the makers of semaglutide, included 17,604 obese or overweight participants with cardiovascular disease but no diabetes. They were randomised to receive weekly injections of either semaglutide or a placebo and were followed-up for three years. The aim was to check for any reduction in deaths, heart attacks, and strokes, as the drug was known to reduce weight. During follow-up, 833 people (4.7%) died. Compared to the placebo group, participants who received semaglutide had lower death rates from all causes, including cardiovascular, non-cardiovascular, and also COVID-19 deaths.

The primary findings of the SELECT trial were published earlier in The New England Journal of Medicine in December 2023. A 19% reduction in cardiovascular mortality, heart attacks, and strokes in the semaglutide group was the highlight.

However, these results also raised questions. For example, why was there an early reduction in deaths — even before the participants lost weight? Typically, the health benefits of weight loss take longer to manifest. For instance, a Swedish bariatric surgery study by Sjöström et al., which also demonstrated reduced deaths from weight loss, had an average follow-up of 10.9 years. Following surgery, although weight loss occurred in the first year, death reduction only occurred much later.

Secondly, the SELECT study participants were not diabetic, implying that the known anti-diabetic effects of GLP-1 agonists could not have accounted for the reduced deaths. Finally, there was unexpected reduction in COVID-19 deaths. The paper did not mention participants’ vaccination status. This leaves unanswered questions about how GLP-1 agonists might affect COVID-19 mortality.

When a clinical trial reports an unexpected benefit in the treatment arm compared to placebo, two possibilities arise — either the treatment is genuinely better, or the placebo group had participants in worse health at the start of the trial. The surprising results from this study were the earlier-than-expected death reduction and the apparent effect on COVID-19 mortality. This warrants a closer look on whether the two groups had important differences at baseline.

Large randomised trials like SELECT are able to minimise such discrepancies. Accordingly, there were no major baseline differences between the semaglutide and placebo groups in terms of age, gender, HbA1c, blood pressure, cholesterol level, BMI, or waist circumference

However, the supplementary tables comparing baseline parameters of those who died with those who remained alive have a striking difference in the use of loop diuretic medicines. Among those who remained alive, only 11.7% were using loop diuretic drugs at the start of the trial, compared to 35.9% among those who later died of cardiovascular causes. Loop diuretic medicines are commonly prescribed for advanced disease conditions of the heart, liver and kidney, and their use could serve as an indirect indicator of the severity of the participants’ health. This suggests that many participants who died during the course of the trial may have had more advanced heart disease from the outset.

Although randomisation generally ensures a balanced distribution of participants, some unevenness could still occur. The total number of people with heart failure was comparable in both groups, which included varying degrees of severity. However, the paper does not specify whether the placebo group had a higher proportion of individuals on loop diuretics, which could indicate more advanced heart failure. Such a discrepancy could have potentially contributed to higher death rates during follow-up. This might also explain the unexpected difference observed in COVID-19 deaths. It is also possible that properties of GLP-1 agonists other than weight loss and control of diabetes are involved here.

Research is essential for advancing medical knowledge. While unexpected findings are not uncommon, it is vital to explore all possible explanations before drawing conclusions. GLP-1 agonists are already recommended for people with diabetes, and this study suggests they may also benefit overweight and obese individuals without diabetes. These findings could impact medical practice, particularly if further studies confirm the results.

(Rajeev Jayadevan is Chairman, Research Cell, Kerala State IMA)

Published – September 14, 2024 09:00 pm IST