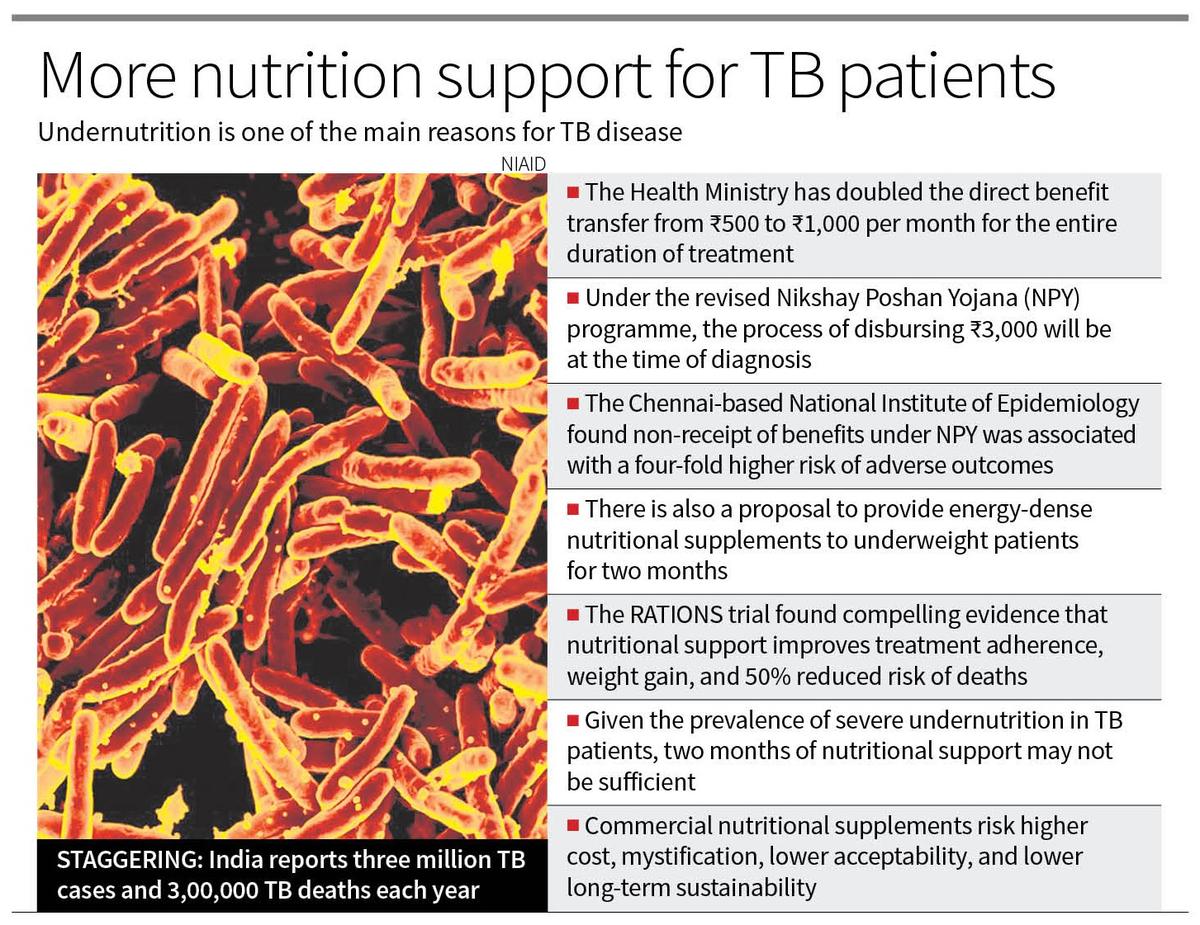

TB remains a major public health problem in India with an estimated three million new patients with TB and 3,00,000 TB deaths every year. The recent announcement by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare of doubling the direct benefit transfer from ₹500 to ₹1,000 per month in the Nikshay Poshan Yojana (NPY) for the entire duration of treatment, and initiating the disbursement of ₹3,000 at the time of diagnosis is a welcome step. There is also a proposal to provide energy-dense nutritional supplements to underweight patients for two months and to extend nutritional and social support to the families. India is probably the only high TB burden country to roll out such a large-scale scheme that will address the nutritional needs and the economic distress of the patients.

TB remains a social disease in its causation and its outcomes. Social factors associated with poverty, such as overcrowding and undernutrition increase the risk of TB. Most other risk factors, too, like diabetes, smoking, and alcohol, are either more prevalent or are poorly managed in those living in poverty. Undernutrition contributes to more than a third to nearly half of new TB cases in India. Poor access to primary care, poor quality of care, and poor adherence generate a vicious cycle leading to severe disease and risk of death in the poor. Their predicament is grim as they face income loss, direct and indirect costs due to the disease and its treatment, food insecurity, and often an inability to return to usual work because of the sequelae of the disease.

The Nikshay Poshan Yojana is crucial because severe undernutrition is common in people with TB in India — the average weight of adult men is 43 kg and 38 kg for adult women at diagnosis. Without nutritional support, such patients have worse outcomes during and after treatment. These patients often do not have early weight gain, and this poses a high risk of death; even after effective treatment, undernutrition may persist, increasing the risk of recurrent TB. Studies also show a high prevalence of food insecurity in TB-affected households. Nutritional support thus has a sound clinical, public health, and ethical basis. It aligns with India’s 2017 adaptation of the WHO guidelines on nutrition care and support for patients with TB. There is compelling evidence that nutritional support with food baskets can improve treatment adherence and weight gain, allow a successful return to work, and reduce mortality risk. In the RATIONS trial, in patients provided with a 10 kg per month food basket, early weight gain was associated with over 50% reduced risk of death. Moreover, a low-cost intervention of six months with a food basket of cereals and pulses with micronutrient pills for family members reduced new cases by up to 50%, akin to a vaccine.

An evaluation of the NPY programme over five years by the Chennai-based National Institute of Epidemiology (NIE) has significant lessons. An important challenge is that the TB programme staff, now engaged in other new initiatives, feel overburdened by the processes of facilitating the direct benefit transfer. Another issue is that the most vulnerable communities cannot access the benefit because of a lack of proof of identity, residence, bank accounts, or distances involved. The NIE evaluationshowed that non-receipt of benefits under NPY was associated with a four-fold higher risk of adverse outcomes.

As clinicians and researchers working in this field, some clarifications and implementation issues must be addressed. First, there is a need for dedicated human resources for NPY activities, and these can also be utilised for newer initiatives like evaluating household contacts. Second, there is a need for locally contextualised counseling material for patients and family members to emphasise nutrition as an essential component of treatment. It should include locally available and culturally acceptable foods to optimise the intake of energy and calories. Quality protein intake is deficient in poorer households. Pulses, soybean ground nuts, milk, and eggs are more cost-effective sources than supplements derived from them, and this needs particular emphasis in the counseling. Third, given the evidence supporting food baskets, the recommendation related to energy-dense supplements should be deliberated upon. Commercial nutritional supplements risk higher cost, mystification, lower acceptability, and lower long-term sustainability. Given the prevalence of severe undernutrition in our patients, two months of nutritional support may not be sufficient.

Fourth, with regard to Nikshay Mitra, the coverage of the most vulnerable is inadequate, and a redesign is warranted. Due to the significant stigma of TB, an explicit advisory against pictures of patients and families receiving food baskets is needed. Finally, nutritional, financial, and social support initiatives can work best if they are integrated with other aspects of care — uninterrupted supply of drugs, better management of comorbidities, better evaluation of patients at diagnosis for high-risk features, and referral for in-patient care as is being done in Tamil Nadu — are vital to ensuring better outcomes.

(Anurag Bhargava and Madhavi Bhargava work in the departments of Medicine and Community at the Yenepoya Medical College, Mangalore, and led the RATIONS trial)

Published – October 19, 2024 09:15 pm IST