On a clear, bright morning in late August, Megan D’Souza, an Indian student at Ukraine’s National Pirogov Memorial Medical University, Vinnytsya, stood in front of a hotel overlooking the Sophia square in Kyiv, the capital. With her stood a few hundred Indian students from the university, all eagerly waiting to welcome Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who was visiting for a day. This was his first trip to the east European country since Russia invaded Ukraine on February 24, 2022. “This is a historic visit by an Indian Prime Minister and we are part of history,” D’Souza said. Slogans of ‘Bharat Mata Ki Jai’ rent the air.

While the mood was jubilant at the hotel, elsewhere, there were signs of a country at war. Kyiv was under curfew every day from midnight to 5 a.m. The streets emptied out past 11 p.m. Crowded areas were blocked at night. Barricades had been erected in front of complexes, and barbed wires encircled important buildings.

Several buildings contained bomb shelters. Vinayak Niwas, a 26-year-old student from Bihar, explained, “While basements of buildings, shopping malls, and parking areas have been converted into shelters and furnished with basic amenities, there are also Soviet-era bunkers around. Those were built to withstand heavy bombardment and allow people to seek refuge for longer.” Staff in hotels gave directions to shelters as part of their routine instructions.

Statistics vary on the number of deaths in Ukraine since the war began. Ukrainian officials have said Russian “invaders” had killed more than 12,000 civilians, including 551 children, while the London-based Action on Armed Violence charity reported that 7,001 people had been killed as of September 23, with more than 20,000 civilians injured.

Russia’s invasion has displaced millions of Ukrainians and destabilised the economy. According to the European Parliament, “More than 6.4 million Ukrainian refugees were registered worldwide and there are close to 3.7 million internally displaced people (the two groups together representing 23% of Ukraine’s pre-war population).”

The Russian bombardment has equally affected millions of people of other nationalities who study and work in the country. Among them are Indians — mostly students, businesspersons, and those who married locals and have settled in Ukraine.

At a crossroads

When the war broke, Niwas said the situation in Vinnytsia, about 270 kilometres by road from Kyiv, was “completely chaotic”. He recalled, “I felt the vibrations when the first bomb hit the ground a couple of kilometres from us.”

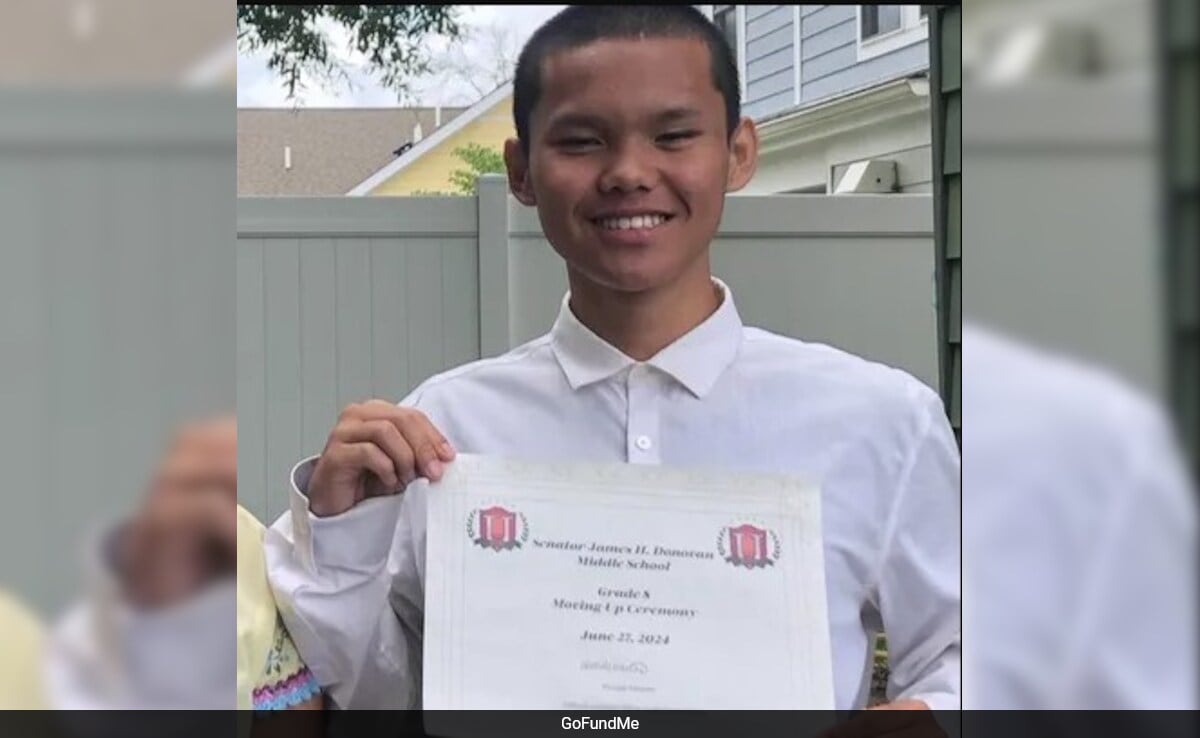

Students arrive at Hindon Airbase in Uttar Pradesh after being evacuated from Ukraine by the Indian government.

| Photo Credit:

R.V. Moorthy

In February and March 2022, around 22,500 Indian nationals were evacuated from Ukraine. Of them, 18,278 were brought back to India under Operation Ganga, an evacuation mission carried out by the Indian government. Most of them were students.

Shrujan Laxmikant Mehta, 23, from Somnath, Gujarat, was evacuated through Romania. “Along with others, I travelled by bus, waving the Indian flag,” he said. Mehta returned to Ukraine via Poland in 2023.

Many students who are pursuing medicine in Ukraine said they had moved because an MBBS course is expensive, even prohibitive for many, in India. According to education consultancy sites and students, the fees for a MBBS course at a government medical college in India is ₹10,000-₹50,000 per year. But at a private medical college, it can range anywhere between ₹3 lakh and ₹25 lakh per year. Others said that these are lower estimates and that the actual cost can be several lakh rupees higher.

To add to the problem of costs is the challenge of intense competition. Of the 17 lakh students who appear for the medical exam every year, only about 80,000 students secure admission for an MBBS course, as per a September 2022 report by Mumbai-based investment consultants, Anand Rathi Advisors. “The limited number of seats and a high minimum threshold for government colleges coupled with lofty fees is compelling students to pursue medical education in foreign countries. China, Ukraine, the Philippines and Russia account for 60% of the student outflow from India each year,” the report stated.

Students said that Ukraine, Russia, and other Central Asian countries have emerged as popular choices for them to pursue medicine as an MBBS course in these countries is affordable. The average annual tuition fee of medical education in Ukraine is around 2 lakh Hryvnia or UAH (₹4.2 lakh). “Since universities in the European Union have the European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS), a standard means to compare credits, we can easily get admission into good postgraduate colleges and get jobs in Europe,” Mehta said. “Also, the qualifying ratio of the Foreign Medical Graduates Examination, which is required for foreign degree holders to practise medicine in India, is also very good for Ukrainian universities,” he pointed out.

In February-March 2022, the students who returned to India had two options: they could either seek transfers to universities in other countries or wait until it was safe to return to Ukraine. Getting a transfer to a university in India was out of the question as the National Medical Commission Act, 2019, does not permit students to migrate from foreign universities to India.

Tanmaya Lal, Secretary (West), Ministry of External Affairs, said that the Ukrainian Medical Council facilitated the transfer of some students who had returned to India, to other universities and countries.

But many others had to figure it out on their own. To obtain transfers to universities in Europe or Central Asia, the students had to either begin their course from scratch or pay extra, said officials. While it was relatively easy for students in the first few years of their course to restart elsewhere, for those in the fifth and sixth year, it was a difficult call to take.

“When I was in India, I would write at least 50 emails a day just begging various universities to take me in,” recalled D’Souza, who is in the final year of her course. She wrote to universities all over Europe which had an ECTS. “No one was willing to take me. And even if they were willing, I would have had to start from the beginning, which was not an option for me. It was really hard. I came back to Ukraine not only because it was hard to get transfers elsewhere but also because this was the cheaper alternative,” she said.

Also read | Ukraine-returned Indian medical students relocating to Uzbekistan

While some students said they had moved to Hungary and even secured full scholarships, they had to start their course once more. Samarkand State Medical University in Uzbekistan, for instance, accommodated more than 1,000 Indian medical students from Ukraine after the Indian Embassy in Ukraine reached out to them. “We evaluated the requirements of such students and decided that enrolling them with a semester back would be a viable option to provide equivalence,” said Zafar Aminov, the Vice Chancellor, speaking to the media earlier.

In 2022, the National Medical Commission of Ukraine issued a notice allowing a mobility programme for those students affected by the war. Under this, the Odessa National Medical University found a partner institute in the Georgia National University SEU, the only university which took part in the programme from Georgia, according to Ashu Rawat, Founder and Director, Leader Education, based in Odesa. Under the mobility programme, students could complete the remainder of their degree in Georgia and obtain the degree from their original university upon completion. “Around 200 students took this option. It was a very successful programme,” Rawat said.

During a media interaction on August 23, External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar acknowledged that some students have come back to India since the evacuation due to academic compulsions. He said there are 2,000-2,500 Indian students in Ukraine at present. “If you’re asking us what advisory we would give them, we would still urge caution, because you can see there is a conflict on. I mean, it depends, again, on the place, on the city. But our hope is that this conflict will come to an end, life will return to normal, and that we will see the full return of Indian students in due course,” he added.

The journey back

Returning to Ukraine was not only dangerous, but also difficult for students like D’Souza. There were two ways of returning to Ukraine: via Poland or through Moldova.

Obtaining a Polish visa was challenging for many in the early days of the war. Mehta managed to get it, but many others could not. “The biggest issue that the students who wanted to return in the early days faced was lack of connectivity and communication,” said Rawat.

While Moldova did issue e-visas for Ukraine, it stopped when the war began as it struggled to cope with the growing pile of applications. Plus, the country had security concerns.

“At that point, there was no Moldavian Embassy in India,” said Rawat. “There were also attempts by middlemen to get money from the students by promising to secure visas for them,” he added. In April 2023, Moldova announced that it would open an embassy in India. The Moldovan Ambassador arrived in India in June 2023. This helped many students get a Moldovan visa.

Lal said, “Around 2,100 Indian students are enrolled with the Ukrainian universities at this stage. Of them, over 1,000 Indian students are pursuing studies in person in Ukraine.”

Increasing expenses

Ever since she returned, the situation has “not been bad,” said D’Souza. “Yes, we hear the siren at least six times a day and we have water and electricity cuts. But I have only a year to go before I finish the course, so it’s fine.”

Several students complained that the prices of utilities have increased. While the tuition fees have remained the same, university hostels have hiked their fees, they said. “When I came to Ukraine in 2019, the hostel fees every month was 800 UAH, which is about ₹1,600. It was increased to ₹1,000 UAH (₹2,030) last year. Then, it became 1,850 UAH (₹3,760) per month,” one student said. “The prices of daily essentials such as rice, oil, and eggs have also increased. So, our expenses have doubled.”

The students said they raised these issues with the management, which simply shrugged and declared that it was helpless given the ongoing conflict. The students said they still preferred to stay in university hostels, which are safer and more convenient than apartments.

“As there are power and water supply cuts, an induction stove at my university hostel — there is one on each floor — works for only three hours a day. So, all the students line up to cook during that time,” a student said.

Niwas returned to Ukraine in November 2022 as he could not get a transfer to another university. “I found it stressful when I came back. There were sirens blaring daily for hours. But after 2-3 months it got quieter. It is better now,” he said.

Impact on business

Meanwhile, businesspersons said they were worried about the seemingly endless conflict. “During the first few months of the war, businesses suffered a lot due to uncertainty. While they were back on track later, the economy is still down. There is large-scale migration from front territories, recurring electricity shutdowns, increasing inflation, etc.,” said Rajeev Gupta, co-founder and director of the Kusum Group of companies, which produces pharmaceuticals. “There are no flights or vessels coming into Ukraine, so the supply chain has become long and expensive. What took 20 days earlier takes 70 days. The cost of utilities has gone up,” the Kyiv-based businessman said.

However, Gupta believed that he is better off than others. “There are some industrial sectors that continue to work the same way even if there is a crisis. These include food, pharmaceuticals, and alcohol. The pharmaceutical sector is the least impacted by the war. The market size has decreased only due to migration,” he said.

Watch | WhenIndian students were stuck in Sumy

In Sumy, a city in north-eastern Ukraine that was at the centre of the war, there was initially no way to get out. Akhilendra Bahadur Mall, the head of production for Kusum Group, who is based in Sumy, said that the company had tried to use three factory buses to evacuate people, but that plan did not materialise. After persuading the local authorities, and with help from officials from the Indian Embassy, around 1,000 people left Sumy for India on March 8 in over 20 buses.

There were around 850 Indian students at the Medical Institute of Sumy State University at the time. A small number of them have since returned to Sumy to finish their course.

Sumy continues to be a war zone. This is where the Ukrainian military launched a counter-offensive into Russian territory on August 6. This triggered many Russian attacks on the city. Mall recalled a missile attack on August 16 that hit a parking lot in a residential area, just 500 metres from where he stood. “There was a large crater. The balconies of buildings had cracks,” he said.

Despite these unexpected events, the people are united and remarkably composed, said Mall, who has lived in Sumy for 16 years. “That is the strength of the Ukrainians. In the initial days, people used to help each other, even strangers. I found that highly inspiring.”

dinakar.peri@thehindu.co.in

Published – October 19, 2024 03:00 am IST