U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris and former President Donald Trump are neck and neck in the race for the White House. It is likely that if Ms Harris wins that many of her policies towards India will pick up where Mr Biden left off. There may be some greater emphasis on issues that are important to the left flank of the Democratic party — such as stronger or more public positions if the U.S. has concerns about democratic norms and human rights in the actions of the Narendra Modi government. There will likely also be a greater engagement with groups in the U.S. who raise these concerns. Inter-governmental discussions on these subjects are largely — but not fully — managed behind closed doors and that is likely to continue.

Any step changes in U.S. policy towards India are more likely to appear if Mr Trump becomes President. These changes may result from first order impacts, such as in trade, the energy sector, or the initiative on Critical and Emerging Technologies (iCET). But there are second order changes which could be at least as profound, but felt only in the medium to long term. These might occur through Mr Trump’s approach to the Ukraine-Russia war, the conflict in West Asia, and importantly actions vis-à-vis China, the South Asian neighbourhood and the Indo Pacific.

Outcomes under a hypothetical second Trump administration are uncertain, not least because of the unpredictability that is at the core of Mr Trump’s strategy and approach.

Technology Partnership

Given the breadth and depth of iCET, an initiative launched in 2023 by the Biden administration and Narendra Modi government and led by the countries’ National Security Advisors, it is likely to continue.

Watch: Why are U.S. Presidential elections held on Tuesdays?

Consider cooperation in the domain of outer space, an aspect of iCET , for instance. Mr Trump – especially since his close embrace of SpaceX founder Elon Musk, is continuing to show signs that he will be supportive of space exploration and its commercialization. He sought to promote private space exploration by scaling down regulation while in office and targeted a moon-landing by 2024. The Trump administration also established the U.S. Space Command and the U.S. Space Force.

The ground is set for greater space cooperation between India and the US, whether there is a continuity in policy under a Harris administration or a switch to a Trump administration, especially with India signing the Artemis Accords in June 2023.

However, with Mr Trump there could be some friction points – where manufacturing and iCET projects intersect (for example semi-conductor fabrication in India). If the U.S. is going to support manufacturing in India, Mr Trump may view that as a threat to U.S. manufacturing (it is conceivable that he will think this way about semiconductors). Given, Mr Trump’s mercantilist world view, he is likely to expect something tangible in return and in the short to medium term, rather than playing “the long game” with India, as the Biden administration has said it is doing.

That iCET is helping India acquire advance capabilities so it can potentially become an alternative to China as far as supply chains are concerned – a view held in the US – is not likely to satisfy Mr Trump for at least two reasons. One, this outcome is not in the near term. Two, this outcome greatly benefits India as well. He will expect India to pay.

Defence

In general, Mr Trump can be expected to emphasize the defece aspect of the U.S. relationship with India. The Quad was revived during his administration (Mr Biden elevated it to the leader level). Mr Trump is likely to push India to keep spending on arms from the U.S. ( the two countries recently concluded a $ 3.5 billion deal for India to purchase 31 MQ-9B armed drones from made by General Atomics). One of iCET’s domains is defence innovation and technology cooperation.

Trade

More generally, as far as trade is concerned, Mr Trump has a preference for trade deals, rather than the Biden administration’s framework approach. India has not yet signed on to the Indo Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF). Mr Trump said in 2023 that he would undo this framework. He is likely to follow through – he took the US out of the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP) days after his inauguration.

Mr Trump views trade balances as profit and loss statements. He has repeatedly suggested that India and China ( sometimes also referring to the European Union) as being “tough” on trade.

He called India the ‘tariff king’ when he was President and took India out of the U.S.’s preferential trading program, the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP). If elected, Mr Trump is likely to seek the equalization of tariffs across product categories with regard to US-India trade.

Mr Trump is also likely to want tariff equalization across product categories. He told Bloomberg’s John Micklethwait that ‘tariff’ was the “most beautiful word in the dictionary”(since then, as November 5th got closer, he had downgraded it to third place, after ‘love’ and ‘religion’).

A Trump administration is also likely to want to sign a trade deal with India, at least a limited-scope trade deal for starters. This was under discussion towards the end of Mr Trump’s first term but nothing came of it.

India had purchase U.S. energy during Mr Trump’s administration after it slapped sanctions on Iran and Venezuela, cutting off those sources of oil. Given the focus on domestic fuel production during the campaign, Mr Trump is likely to not just drill for more petroleum, but also seek markets for U.S. energy in India and other countries.

China and Russia

Mr Trump has said he will end dependence on China in critical sectors – electronics, steel and pharmaceuticals. India could benefit from this.

There are, however, larger questions about his approach to Chinese President Xi Jinping. Mr Trump says he gets on with Mr Xi, while also mentioning China in virtually every campaign speech as an economic competitor. Mr Trump began a trade war with China during his time in the White House.

The former President’s stance on Taiwan is complicated. He has said Taiwan should pay the U.S. for defending it ( likening the U.S. to an “insurance company”) and has been ambiguous about whether he would go to Taiwan’s defence if China were to attack it. He is nevertheless going to have to negotiate with Republicans (and Democrats in a split Congress); there is little appetite on both sides of the aisle to placate China. Mr Trump is also expected to have in his inner circle China hawks, e.g. , Tennessee Senator Bill Hagerty, former U.S. Ambassador to Germany Ric Grenell and former Defense Department official Elbridge Colby. At this stage it is largely futile , in the case of China and Russia, to identify what the outcomes of a Trump 2.0 situation will be.

With regard to Moscow, since Mr Trump left office, Indian purchases of Russian oil have increased significantly (from about 2% to just over 40% by some estimates between 2021 and May 2024). India has been accused of helping to fund Russia’s invasion of Ukraine through oil purchases and has defended its purchases as being in its national interest. New Delhi has also noted that had it stopped buying Russian oil, the global price of oil will have increased with restricted supply.

How these dynamics change in the medium to long term will depend on how the path of the Russia-Ukraine war is shaped under Mr Trump who has suggested a keenness to bring the conflict to a swift end. This is likely to involve significantly more unfavourable terms for Kyiv than are perhaps open to it now, going by the adulatory remarks Mr Trump has made about Russian President Vladimir Putin, his testy relationship with Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy and his distaste for American money going to Ukraine’s assistance.

In the approach to any resolution to that conflict, there is the more immediate issue of sanctions against Russia. Even as recently as last week (October 30), the U.S. sanctioned 19 Indian entities for providing “dual use” technologies to Russia.

There are Republicans in Congress who would oppose the removal of Russia-related sanctions.

“We don’t know how that is going to factor into Trump’s calculations,” said Lisa Curtis who leads the Indo-Pacific program at the Centre for a New American Security. Ms Curtis was the senior director for South and Central Asia in Mr Trump’s National Security Council.

“ All we know is that Trump will probably put more effort into ending the war than the Biden administration has,” she added.

Alleged assassination plots

Officials who served as bureaucrats in both Democratic and Republican administrations are united in one thing – that neither a Democratic nor Republican president would look the other way if a foreign government attempted to assassinate a U.S. citizen on U.S. soil (abstracting from whether or not that happened in the Sikhs for Justice leader Gurpatwant Singh Pannun case, as alleged by the U.S. Department of Justice).

Pro-Khalistan figures, have openly propagated separatism in the Indian context as well as issued threats against Indian assets (for instance, Mr Pannun’s threats in October 2022 with regard to Air India flights). Nevertheless, thus far, these activities have appeared to avail of protections offered by the First Amendment (of the U.S. Constitution). It is unclear if this would change under a hypothetical Trump administration.

“I think certainly if there’s any information you know, brought to him [ Mr Trump] that demonstrates any involvement in any kind of terrorism or threats to India, a Trump administration would investigate those and act on those. But it really depends on the information that India presents and how credible it is, and what it means,” Ms Curtis told The Hindu.

“Trump … he is ‘America First’. He’s going support US citizens … he’s not going to like the idea of another country trying to assassinate a US citizen on US territory,” she said, adding ,

“ I don’t think any US president would look favorably on that kind of thing.”

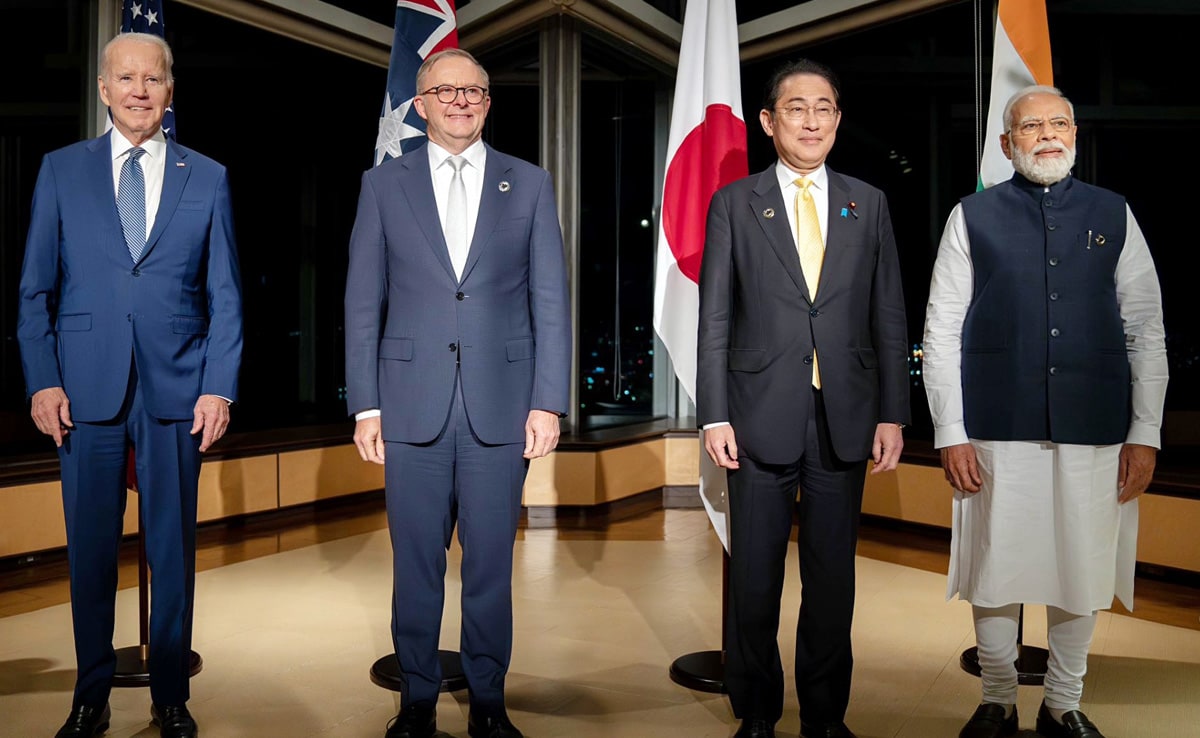

At least some American policy-makers suggest that the meeting between three Sikh groups and White House officials just ahead of Mr Modi’s visit for the Quad Summit in September this year, was neither out of line nor something for India to be alarmed by.

Immigration

Mr Trump’s biggest campaign focus has been cracking down on illegal migration (Indians represent the largest group of Asian undocumented migrants in the United States). However, his

Rapport between leaders

Another aspect of the US-India relationship that has been discussed is the apparent connect between leaders. Mr Biden has emphasized the role of his personal rapport with other politicians – whether from other countries or in the U.S. Congress – in delivering mutually favourable outcomes. He and Mr Modi appeared to have developed a good relationship. There are no signs of an especially good relationship between While Mr Modi and Ms Harris appear to have a perfectly good dynamic, there are no signs that it is especially strong.

Mr Modi and Mr Trump also had on display an apparent bonhomie in previous years – seen for example in the ‘Howdy Modi’ rally in Houston in 2019 and Mr Trump’s visit to India in early 2020.

Officials, past and present, in Washington DC, have suggested that interpersonal relationships at the leader level are important in setting the overall tone of the engagement at the bureaucratic level and a good rapport between leaders can encourage ministers, negotiators and officers to raise the ceiling of their ambitions. Notwithstanding the strength of interpersonal bonds, there is a floor; and this likely to be felt sooner in a Trump administration than in a Harris administration , because of Mr Trump’s transactional approach.

Published – November 04, 2024 08:14 pm IST