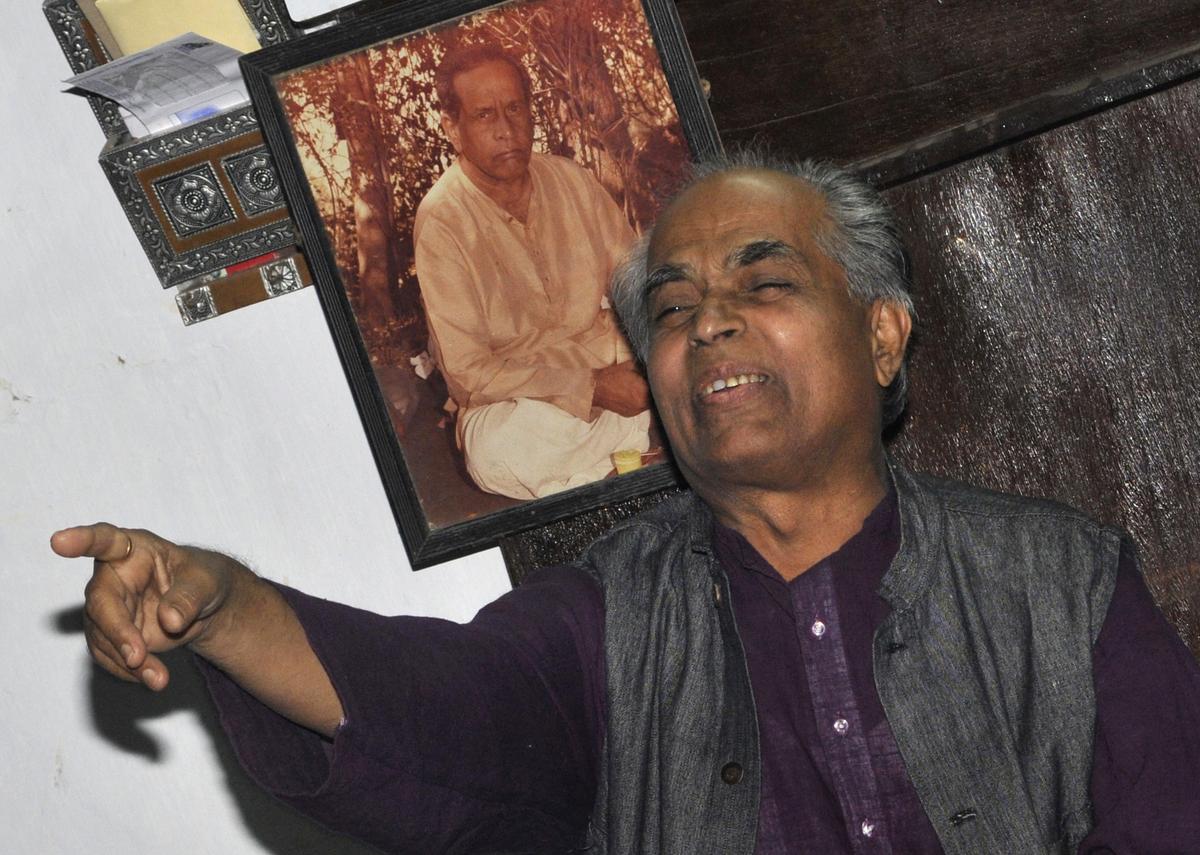

Dr. Najaraja Rao Hawaldar.

| Photo Credit: BY SPECIAL ARRANGEMENTS

Dr. Nagaraj Rao Havaldar, a vocalist of the Kirana gharana, has dedicated his life to preserving and promoting Karnataka’s rich classical music legacy. A disciple of Pt. Madhava Gudi, who was himself a student of Bharat Ratna Pt. Bhimsen Joshi, Dr. Havaldar’s music embodies the depth and subtlety of a renowned lineage.

Bhimsen Joshi

| Photo Credit:

BHAGYA PRAKASH

Recently, he presented Sangeeta Ganga Kaveri, a lecture- demonstration organised by Azim Premji University at the Bangalore International Centre (BIC), highlighting Karnataka’s unique status as a state that has nurtured stalwarts in both Hindustani and Carnatic traditions.

Madhava Gudi

| Photo Credit:

BHAGYA PRAKASH

This legacy owes much to royal patrons like the Wadiyars of Mysore, who fostered a vibrant cultural exchange with the Baroda court, enriching Karnataka’s musical landscape. The flourishing of Hindustani music in North Karnataka and the resilience of Carnatic traditions in the south testify to this diversity.

Sawai Gandharva

| Photo Credit:

HANDOUT_E_MAIL

In this interview with The Hindu, Havaldar delves into the historical, cultural, and social roots of Karnataka’s dual musical heritage and discusses how these traditions continue to inspire artistes and audiences across generations.

Gangubai Hangal

| Photo Credit:

Bhagya Prakash_K

How did Karnataka come to have a rich legacy that combines Carnatic and Hindustani traditions? What are the historical reasons for it?

The kings of Mysuru were responsible for the rich Hindustani and Carnatic traditions we have today. They would invite artistes from cities like Baroda to their courts, which would involve at least four days of travel. After Mysuru, they would eventually perform at cities like Belgavi, Dharwad, Hubbali and other places. That is how, slowly, the seeds of Hindustani music were sown in North Karnataka. The influence of Bombay Natya Sangeeth on North Karnataka was also very strong in those days, which too contributed to the Hindustani traditions in Karnataka.

Did these two traditions remain aloof or did they intermingle in creative ways? Can you give examples of it if they did interreact creatively?

Before the 13th century, we had only one form of classical tradition. By and large the content of Indian classical music was spiritual and religious… Hindustani music’s Raag Bhairav is Mayamalavagowla Raga in Carnatic music, Raag Malkauns is Hindola Raga, Raag Shudh Sarang is Mohanakalyani Raga and so on. Both traditions have always had corresponding Ragas, as they come from the same source.

Though much is said about North-South divide in Karnataka, even after years of unification, do you think it has led to cultural enrichment despite politically troublesome issues?

Ustad Dagar calls me during every festival to greet me, and vice versa. Bheemsen Joshi’s guru was Sawai Gandharva, and his guru was Ustad Abdul Kareem Khan. When Abdul Kareem Khan started his music school in 1900s, he would take a written bond and commitment from his students saying that he/she would study for a minimum of seven years. Because he valued his art so much. Abdul Kareem Khan taught Sawai Gandharva, who in turn taught a Parsi, a Madhwa, a Vokkaliga, and nothing came in between. Music is a great unifying and connecting factor even today.

Dharwad was traditionally centre of Hindustani and Mysuru Carnatic music. Have these two cities changed in their musical landscape?

Not much change has been seen in the musical landscape. Dharwad is still the centre for Hindustani and Mysuru for Carnatic. However, what has changed is that the number of performers have increased, due to the artificial surge in the opportunities created. Earlier it was only the Dasara celebrations or Hampi Utsava, but nowadays every district has a Utsava or a festival. Who selects the artists for these festivals? The local MLA… What is his/her expertise in selecting who is going to perform? That has to go.

Would you say Bengaluru’s musical scene is vibrant or has commerce as well logistical issues like traffic and absence of venues marred it?

Despite having transport conveniences like the metro, there are still many islands formed in the city. For example, Malleswaram is an island for music lovers, but if you do a programme in Basavanagudi, the audience from Malleswaram will think twice on coming. Also, the generation which by and large listens to traditional music is above the age of sixty. With such audiences, they have very protective children who do not want to send them, or the elderly are not independent enough to go on their own. With COVID-19, a new menace was introduced that is the facility of having things online. Now, whenever there is a concert by me, people ask if it is available online. These are the new challenges for musicians.

You are well known for your rendering of both Dasa and Vachana literature. How have these two great literary traditions influenced our music?

These two literary traditions have influenced our music immensely. My parama guru, Bheemsen Joshi, had started a unique programme called Dasavani, where he would sing Dasa Padas for four hours well withing the classical music traditions. There was no bargaining in terms of classical rendering. He set a trend, and this inspired many others to start concerts and concepts like Sharanavani, a programme on Vachanas. Dasara Padas were sung in the Mysuru court, and more such programmes were created.

You have not just been a performer but have trained several young talented singers and musicians, including your own children. As the years go by, do you think children or music lovers of this age have the same urge to learn music your generation had many years ago?

There is an unhealthy hurry about being a performer for many of the young these days. For example, 20 years ago, a couple came to me with their teenage child and said that their son had been qualified for the semi-finals of a reality show and he had to sing Nambide Ninna Naada Devatheye, which was sung by Bheemsen Joshi in the film Sandhya Raaga.

They said I would be paid a huge amount, my teaching sessions would be telecast and that I would get a lot of publicity. It is not an easy song to sing. When Bheemsen Joshi sang this song, he was in his early 40s and had already put in 30 years of practice in music. But these parents wanted me to teach this song to a 14-year-old, who had never even held a tanpura in his hand, within a weeks’ time. I told them if Yuvaraj Singh can teach me how to hit six sixes in a week, then I will teach their son how to sing the song. They never came back to me. You must learn to have patience, if you want to learn music.

Published – November 12, 2024 09:00 am IST