The first mission

Born on August 1, 1944 in Koltubanovskiy village in Orenburg Oblast, Soviet Union, Yuri Romanenko was the son of a senior commander on military ships (father) and a combat medic. He did some of his schooling in Kaliningrad after his family moved there, and counted hunting and underwater fishing among his hobbies.

Following a brief stint doing odd jobs, he joined the Chernigov High Air Force School in what is now Ukraine in 1962. He graduated with honours in 1966 and stayed on to train students, while fine-tuning himself for the demands of a cosmonaut. By 1970, he was cleared and ready for space flights.

It was another seven years before Romanenko had his first experience of space. As the flight commander on Soyuz 26, Romanenko, along with engineer Georgi Grechko, was launched to space on December 10, 1977. During their 96 days in orbit, they met with Soyuz 27, Soyuz 28, and Progress 1.

Yuri Romanenko (left) and Georgi Grechko.

| Photo Credit:

THE HINDU ARCHIVES

In his first mission, Romanenko performed a space walk for an hour-and-a-half. Leading up to this, there was a moment when Romanenko had pushed against the wall and flew outside, but without harnessing himself to the safety cord. Grechko grabbed hold of him to ensure he didn’t leave the space station, but Romanenko would have nevertheless not floated away because of the electrical cables that were attached still. Grechko joked about the whole accident when the duo met the press, going as far as saying that Romanenko was on the verge of death.

Cuban connection

Romanenko’s second space mission began on September 18, 1980 when he was part of a historic flight aboard Soyuz 38 alongside Arnaldo Tamayo Mendez. This flight was special as Mendez was not only the first Cuban cosmonaut and the first Latin American to fly into space, but also the first person of African descent to make a space-bound journey.

Over seven days, the duo completed 124 orbits around the Earth, while conducting science and health experiments. A total of nine experiments were performed, including those that studied stress, blood circulation, immunity, balance, and the growth of a single crystal of sucrose in weightlessness. The two returned to Earth on September 26.

Mendez and Romanenko talking with Pilot-cosmonaut of USSR Georgi Dghalabov (left).

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

Following his retirement in 1988, Romanenko and his family were invited to Cuba. Cuban revolutionary Fidel Castro – the country’s President at that time – not only personally met Romanenko, but also organised a social tour that accommodated Romanenko’s interests in underwater fishing and hunting.

326 days in space

Romanenko’s third and final voyage to space was his longest. In fact, it wasn’t just his longest, but the longest there had been until then!

Lasting from February to December 1987, the Mir EO-2 expedition – also called the Mir Principal Expedition 2 – was the second long duration expedition to the Soviet space station Mir. Launched aboard a Soyuz TM-2 along with Aleksandr Laveykin on February 6, 1987, Romanenko returned to Earth aboard a Soyuz TM-3 on December 29 – after 326 days in space!

Yuri Romanenko

| Photo Credit:

“Роскосмос” or “GCTC” or “РКК Энергия” / Wikimedia Commons

During this stay, Romanenko performed three space walks – on April 11, June 11, and June 16. The space walk on April 11 was an emergency extra-vehicular activity (EVA) that lasted 3 hours and 40 minutes, during which Romanenko and Laveykin had to exit Mir to repair a problem with Kvant (first module to be attached to the Mir Core Module). Discovering a foreign object (probably a trash bag they had left between Progress 28 and Mir’s drogue) lodged in Kvant’s docking unit, the duo pulled it free. Once it was discarded into space, Kvant successfully completed docking following a command from the ground.

Even though both of them were scheduled to stay throughout, Laveykin was replaced by Alexandr Alexandrov from Soyuz TM-3 in July. This was because ground-based doctors had diagnosed Laveykin to have minor heart problems (tests once he was back revealed that he was fit to fly after all!).

By the time Romanenko returned on December 29, 1987, the pair who went on to break his longest spaceflight record were already in space. Vladimir Titov and Musa Manarov stayed for 365 days, starting on December 21, 1987 and returning the same day the following year. Their record has also since been broken, and it is currently held by Valeri Poliyakov, whose longest single-mission stay lasted 437 days.

Like father, like son

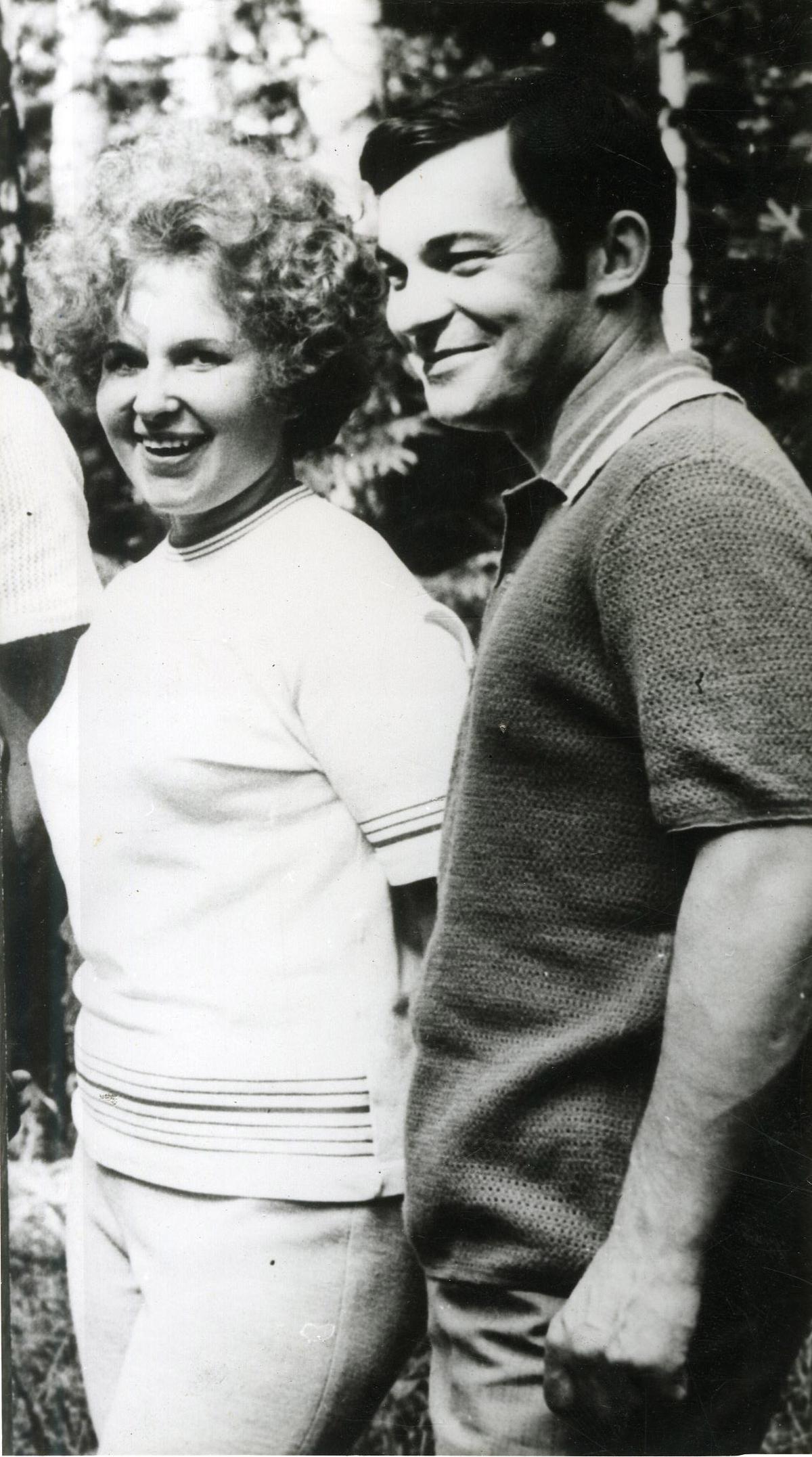

Yuri Romanenko with his wife Alevtina.

| Photo Credit:

THE HINDU ARCHIVES

Married to Alevtina Ivanovna Frolova, Romanenko had two children. Their first son Roman was born on August 9, 1971, while the second son Artem was born on May 17, 1977.

Like his father Yuri, Roman too went on to become a cosmonaut, heading to space on a couple of instances. There have been only a handful of second-generation space venturers, and Roman is one of them.

This means that Yuri and Roman are also among the very few father-son duo where both of them have been to space.

(From left to right) Astronauts Tim Kopra, John “Danny” Olivas, Frank De Winne and Roman Romanenko pose for a photo in the Unity node of the International Space Station in this NASA handout photo taken on September 7, 2009.

| Photo Credit:

REUTERS/NASA/Handout

One quote. Two interpretations.

On returning to Earth following what was then the longest single-mission human stay in space, Romanenko remarked that “The cosmos is a magnet. Once you’ve been there, all you can think of is how to get back.”

This poignant statement can be interpreted in a couple of ways, both of which are deep and symbolic.

On the one hand, the statement can be said to mean that experiencing the vastness and wonder of infinite space can be so profoundly captivating that there is a constant tug in the heart, even after returning to Earth. This tug makes the person yearn to experience the same feeling once again. This pull by an invisible force is likened to that of a magnet.

On the other hand, the statement can also be interpreted to the overwhelming feeling that one might experience when setting out into the cosmos. The celestial beauty that goes along with the awe-inspiring and humbling nature of space can evoke a sense of smallness and insignificance among those who experience it. This, coupled with the longing to “get back” to the comfort and familiarity of Earth, could well be conveyed by this quote. The magnet that is the cosmos in this case then keeps the space traveller attracted to it and holds them spellbound, even when they wish to head back to all that they have been disconnected from.

Published – December 29, 2024 12:29 am IST