Even those with only a cursory interest in Steve Smith’s international career will be aware that he started his days in Test cricket as a leg-spinner, more than 14 and a half years ago against Pakistan at Lord’s. That he batted at No. 8 and No. 9 respectively on his Test debut, and didn’t move up into the top half of the batting order until March 2013, by which time he had played for Australia for close to three years.

The right-hander’s first foray in the top six netted him 92, against India in Mohali. That cemented his position as a specialist batter who occasionally bowled leg-spin. So occasionally, that in the last five years since he returned from a long ban following his involvement in Sandpapergate in South Africa in early 2018, he’s bowled only 20.5 overs for two wickets in the five-day game.

Smith’s status as among the three or four most pre-eminent batters of his generation is well established. Full of quirks and unique mannerisms that coaches across the world urge their wards to steer clear of copying, he has found his own happy medium through which he makes runs. Not attractive runs – seldom attractive runs, actually – but effective, match-saving, match-turning runs. He is a mere 38 short of completing 10,000 runs in Test cricket, boasts 34 centuries, including two in the last fortnight against India, and averages a smashing 56.28, the mark of an all-time great, no matter in which era he plies his wares.

Quintessential

Of all things quintessential Smith, eccentric movements and elaborate leaves included, the most crucial element to his batting are his hands. That might sound silly, considering that without ‘hands’, batters can’t bat. But Smith’s hands are the stuff of folklore. When he says he has found his hands, oppositions beware. It loosely translates to, ‘I am feeling good about the feel of the bat in my hands, here I come’.

When Smith has claimed to have found his hands, the runs come automatically. And in a torrent. Before the 2017-18 Ashes when he spoke about re-finding his hands, his average was an astonishing 137.40. Prior to that, in 2015-16, he boasted averages of 214 and 131 in successive series on rediscovering his hands. So, when Pat Cummins pronounced in Perth, ahead of the first Test against India, that Smith’s hands too had come with him to the Western Australian capital, there was good reason for the Indians to start wondering what carnage lay in store.

To their good fortune, while the hands came to Perth, the runs did not. Not to Perth, nor to the Adelaide Oval, the venue of the pink-ball Test. His scores in the first three innings were 0 (trapped leg before, first ball, by Jasprit Bumrah), 17 and 2. The famous hands, eh? Where were they?

Very much with Smith, as it turned out. Even when the runs weren’t coming – and one of those dismissals was caught down leg, one of the unluckiest ways for a batter to be dismissed – Smith didn’t fret or fume. He wasn’t anxious, he wasn’t seized of the need to lay bat on ball, to spend long hours wondering when the big one was coming. After all, at the end of the Adelaide Test, he had gone 18 months and 24 innings without a hundred. For a serial century-maker, that wasn’t just unusual, it was unprecedented.

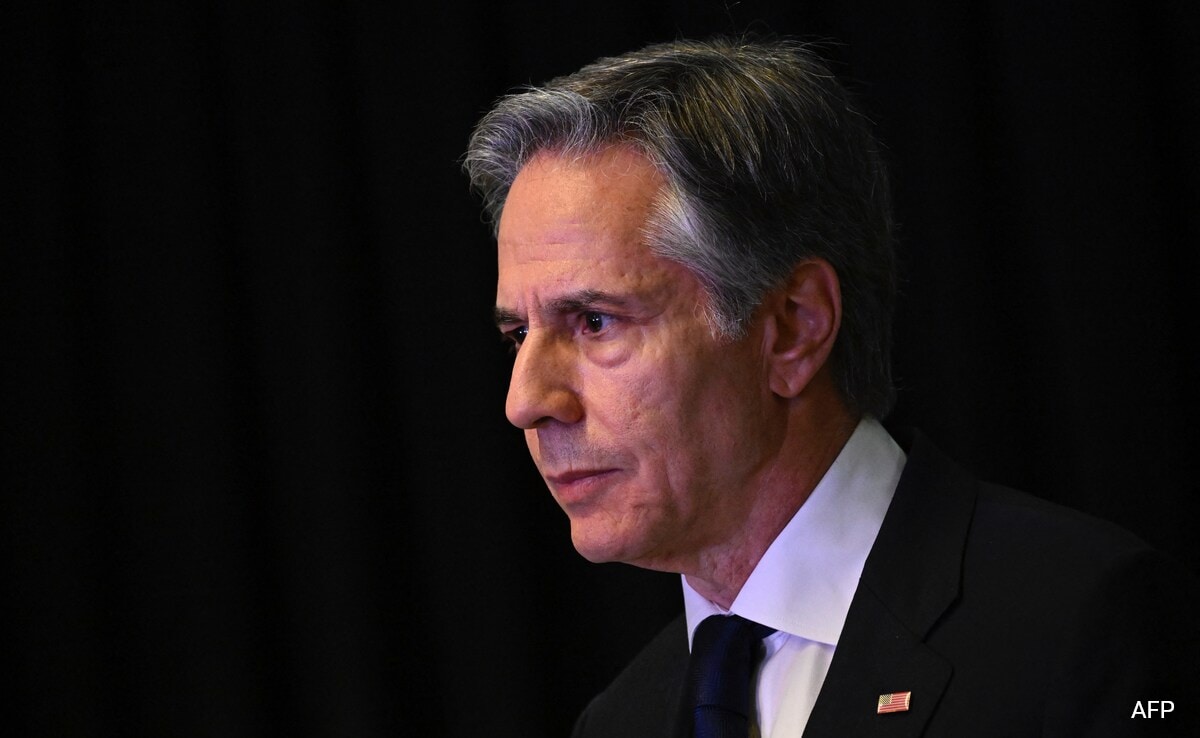

Steve Smith.

| Photo Credit:

AFP

But Smith was insistent that he was happy with his batting. With how he was hitting the ball in the nets. He was adamant that there was nothing to worry about, that it was only a matter of time before the big runs came. Not that anyone in the Australian camp was worrying. They knew from experience that if Smith said he was feeling good about his batting, that was it. Tomorrow, if not today.

That tomorrow came at the Gabba in Brisbane when he ticked over beautifully after a terribly scratchy start when Akash Deep could have had his number at least a dozen times. There were numerous plays and misses as Smith drove optimistically and only connected with thin air. The uninitiated might have wondered what this slight figure was doing with a bat when all he was doing was missing the ball. Then, something clicked and the Smith of old, dangerous and fluid, resurfaced dramatically.

With Travis Head for company, Smith went about systematically dismantling India’s best. From 75 for three, the two added 241 for the fourth wicket to bat India out of the game. The left-handed Head was brutal, punishing, his willow cutting scything arcs; the right-handed Smith was more stately if not anymore orthodox. But gradually, you could see the timing returning, the fluency of his jerky movements making its presence felt, the bat making a sweet sound as the ball pinged off of it, the feet moving freely without the stutters and stumbles and multiple trigger movements that are the clearest giveaways that Smith is not firing on all cylinders.

Smith came to Brisbane with a completely different batting set-up – the back and across movement was so pronounced that he ended up almost outside his off-stump, unafraid to expose his leg-stump though bowlers have started to target that sometimes open piece of real estate more and more frequently – and unsuccessfully – in the recent past. The left leg opened up just a little so that he didn’t end up playing around the front pad, so that he could access areas on both sides of the pitch. It seemed kneejerk, a panic reaction to the three low scores in the first two Tests, but that was far from the case.

This new set-up was a part of the larger plan, a plan that he took only a few days to put into practice. Smith’s trigger movements are seldom the same in two successive Tests, if not successive innings, and he loves to mix things up for various well thought out reasons.

“I’ve changed my set-up pretty much every game I’ve played for the last 15 years, it’s nothing new to me,” he agrees. “I try to adapt, figure out the best way to play for each surface that I’m facing. Clearly, this one (at the Gabba) was a pretty bouncy track, so I was batting out of my crease a little bit to get at the bowler, going across my stumps, and leaving my left leg a little bit open. Perhaps when I’ve been doing my double trigger, I was getting my left leg a little bit closed and those balls that are skidding, I’ve struggled to get my bat down in time. But today, my movements were good today. I felt like I was moving into the ball nicely.”

One of the tangible issues a professional sportsperson grapples with is advancing age. Sometimes, that might have nothing to do with performances, but age does come into play when one embarks on making these subtle but significant changes.

Ask Smith if 35 makes it a little more difficult to usher in adjustments and he remarks, “Not really harder. I’ve been doing it for so long. If I want to change a few different things, it doesn’t take me long to do it. Sometimes, I do it in the middle of an innings. That’s part of adapting to situations and scenarios that are put in front of you and having the confidence to do it. I’ve played for a long time and I know what I’m trying to do out there most of the times.”

It is this honest self-assessment and self-realisation that has pretty much insulated Smith from the undulating highs and lows that some of his peers, the other members of the Fab Four, haven’t been able to avoid. Smith was bracketed in that exclusive club with Joe Root, Kane Williamson and Virat Kohli and while he didn’t exhibit the same flair as the other three, few are more blood-minded or committed to the cause of scoring runs than the former Australian captain whose career was blighted by what happened in Cape Town more than six and a half years back.

That, after having served out his penance which included a ban from Cricket Australia in the immediacy of the ball-tampering saga of 2018, Smith is now officially the vice-captain of the Test side and has led when Cummins has been unavailable speaks to the high esteem in which he is held not just by his teammates but the powers that be in CA.

Calling cards

One of Smith’s calling cards, apart from his strange and impossible-to-ape movements with the bat in hand, is his integrity, which is why his role in the events that unfolded in Cape Town was so hard to comprehend, much less fathom. At a tearful press conference not like the one addressed by Kim Hughes when he resigned from captaincy after another loss in a home Test to West Indies in 1984, Smith owned up his culpability and powerfully bared a human side that touched a chord in even those who categorically castigated him for having brought the game, and Australia’s fair name, into disrepute.

Smith’s biggest victory was in his seamless reintegration with his colleagues, which has then mushroomed into a return to a leadership position. In any case, Smith belongs to the school that doesn’t believe that leadership is defined by the suffix against one’s name. Whether he was entrusted with official responsibility or not, Smith was always going to put his hand up as a leader with an all too human, relatable nature. He is now back, purring and ticking over beautifully after a rare lean patch, and is therefore all the more dangerous because of that.

Published – December 31, 2024 11:51 pm IST