The first advance estimates of India’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2024-25, released by the National Statistics Office (NSO) this week, shows a decline in the real GDP growth rate to 6.4% from 8.2% registered in 2023-24. This is lower than the 6.5 to 7% range projected by the Economic Survey in July 2024. The growth rate of nominal GDP, which is the sum of the real GDP growth rate and the overall inflation rate, is estimated at 9.7% in 2024-25 — significantly lower than the 10.5% growth rate projected in the last Union Budget.

Data discrepancies

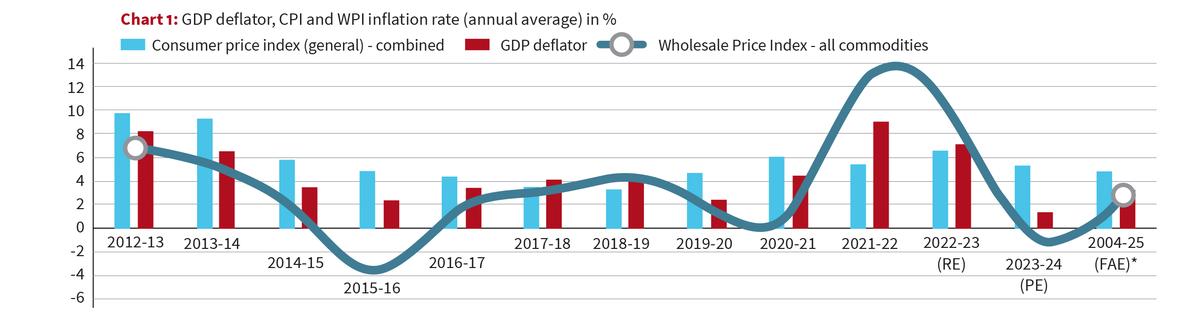

The official diminution of India’s projected GDP growth rate may still be an underestimation of the extent of economic slowdown. Academics and institutional experts have consistently pointed out serious defects in the official GDP estimates, with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) recommending an upgrade of the real sector statistics. An “Informational Annex” to the 2023 IMF Staff consultation report on India had inter alia noted that, “…the compilation of constant price GDP deviate from the conceptual requirements of the national accounts, in part due to the use of the Wholesale Price Index (WPI) as a deflator for many economic activities. The appropriate price to deflate GDP by type of activity is the Producer Price Index (PPI), which is under development. Large revisions to historical series, the relatively short time span of the revised series, major discrepancies between GDP by activity and GDP by expenditure, and the lack of official seasonally-adjusted quarterly GDP series complicate analysis. Together, these weaknesses make it challenging to monitor high frequency trends in India’s economy through official statistics, particularly from the demand side.” The estimation of real or constant price GDP requires the use of a GDP deflator to estimate values of GDP components in constant prices. The GDP deflator being used in India’s official estimates is a weighted average of wholesale and retail price indices. The Wholesale Price Index (WPI), 2011-12 series has shown high volatility over the past decade, leading to inexplicably large divergences between the WPI and CPI inflation rates (Chart 1). This has had serious implications for the accuracy of the GDP deflator and real GDP estimates.

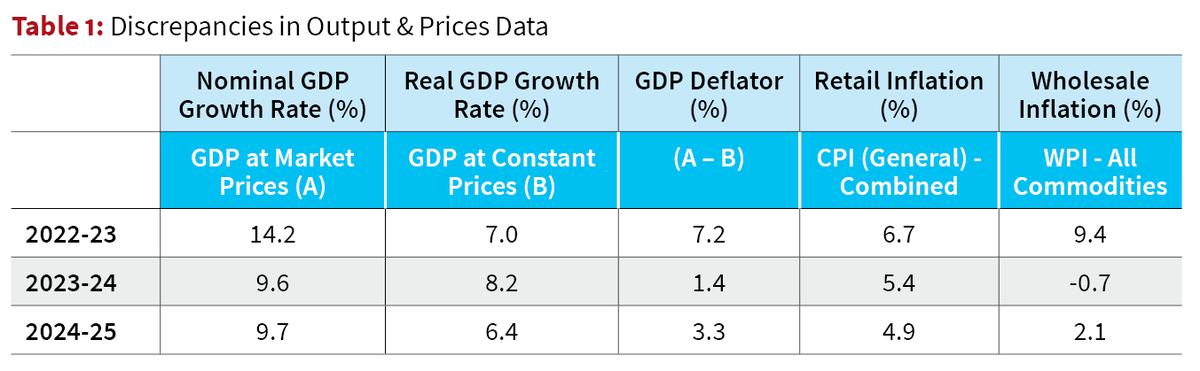

For instance, the nominal GDP growth rate was estimated at 14.2% in 2022-23 and 9.6% in 2023-24, which indicated a sharp decline in growth (Table 1). However, the real GDP growth rate was estimated to have grown from 7.0% to 8.2%, indicating growth acceleration. This implied that the GDP deflator was only 1.4% in 2023-24, even as retail inflation was at 5.4%, because the WPI inflation rate was estimated to have fallen from a high of 9.4% in 2022-23 to a negative of -0.7% in 2023-24. In short, because of high volatility in the WPI, the nominal GDP estimate showed a growth deceleration in 2023-24 but the real GDP estimate reflected growth acceleration. Such anomalous and confounding data on macroeconomic fundamentals invariably lead to delusions and policy errors.

Elusive private investment

Tabled a day ahead of the Union Budget last July, the Economic Survey 2023-24 had taken comfort in the 8.2% growth in real GDP and indicated a vigorous expansion of investment by the private-sector. Yet, the Chief Economic Advisor had asked whether the corporate sector responded positively to the tax cuts of September 2019, and complained about sluggish corporate investments in machinery and equipment and intellectual property products. He criticised the disproportionate allocation of gross fixed capital formation (investment) in the private sector to “dwellings, other buildings and structures” as an unhealthy mix.

Throwing such caution to the wind, the Union Budget relied entirely on a revival of the private corporate capex cycle to announce the ‘Prime Minister’s Package for Employment and Skilling’ with an outlay of ₹2 trillion, aimed at benefiting 41 million youth over a five-year-period. The employment linked incentive/subsidy scheme and the internship programme for one crore youth in five years, were premised on the expectation of massive job creation, consequent to an acceleration of private corporate investment. The fiscal consolidation roadmap, whereby the fiscal deficit was projected to decline from 5.6% of GDP in 2023-24, to 4.9% in 2024-25 and 4.5% in 2025-26, was also announced with the budgetary expectation of the private sector taking a lead in the capital formation process. However, the latest GDP estimates have shown a significant decline in the growth of real gross fixed capital formation from 9% in 2023-24 to 6.4% in 2024-25. A longer view of India’s growth trajectory over the past decade, even on the basis of exaggerated official national account estimates, shows the irrationality of official expectations.

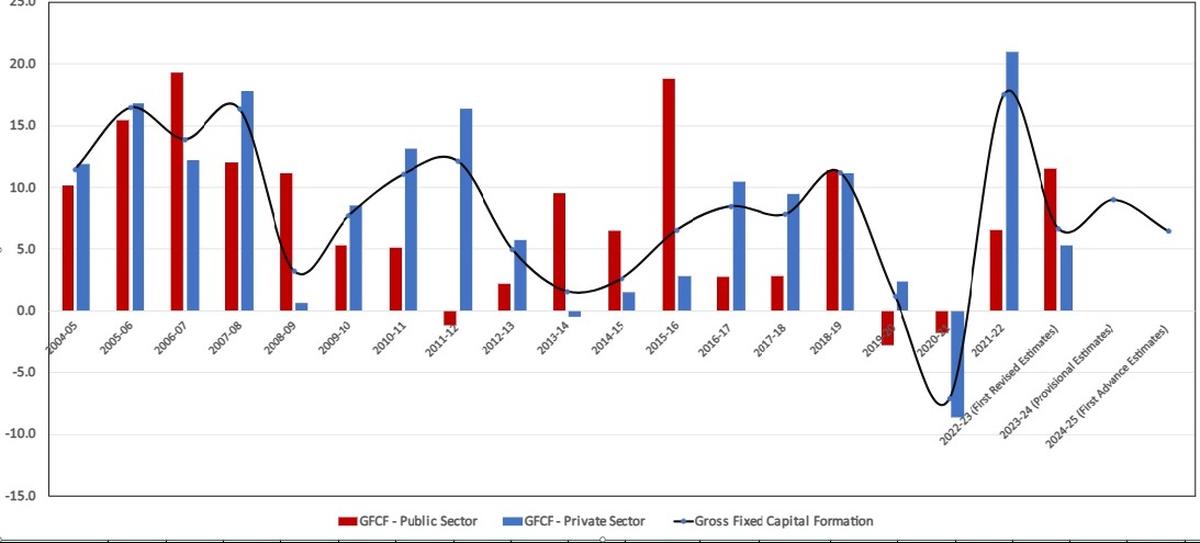

The annual growth rates of real gross fixed capital formation in public and private sectors (%)

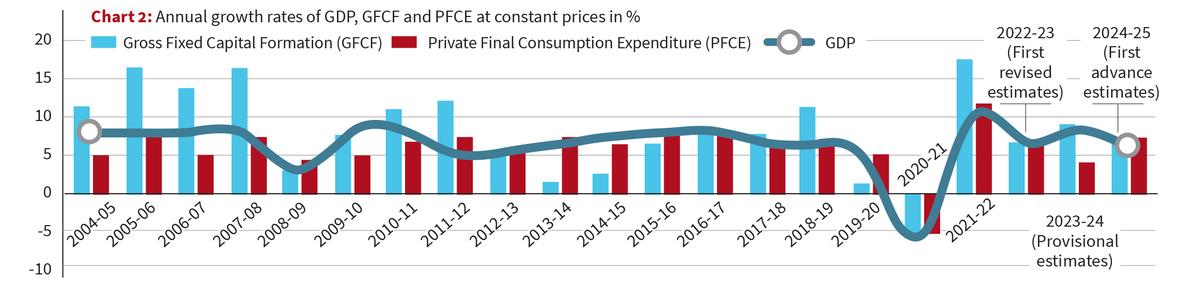

During the 10 years of the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) rule, between 2004-05 and 2013-14, the average annual growth of real GDP was at 6.8%, investment 10% and private consumption 6% (Chart 1). Between the onset of the present regime till the outbreak of the pandemic, that is, between 2014-15 and 2019-20, real GDP grew at an annual average rate of 6.8% (exactly similar to UPA), but real investment growth fell to 6.3% while private consumption growth increased to 6.8%. Thus, economic growth under NDA was not investment led, as was the case under UPA.

Moreover, during the UPA period, real growth in private investment was over 10%, above the growth of public sector investment at around 9% (Chart 2). Under NDA rule, till the pandemic, public investment in real terms grew faster at an average of 6.6% per year, than private investment which grew by 6.3%.

Investment, consumption and output had collapsed in 2020-21 owing to the lockdown induced recession. The recovery in 2021-22 was indeed led by private investment, but the spikes in the growth rates of investment, consumption and output were on account of base effect — it was simply a return to normalcy after the collapse in the preceding year. From 2022-23 to 2024-25, real GDP and investment have grown at an annual average rate of 7.2% each and private consumption at 6%. Post-pandemic there has been one percentage point increase in the annual average growth rate of real investment, and 0.8 percentage point decline in the annual average growth rate of private consumption.

Therefore, there is absolutely no indication of any structural break in the investment behaviour of the private corporate sector so far under the 11 years of NDA rule. The deep corporate tax cuts in September 2019 have failed to spur capital formation and real economic activity; rather it has only helped a short lived spurt in corporate earnings and fuelled a post-pandemic bubble in the equity market. In contrast, the advent of the UPA regime had led to a real investment and exports boom between 2004-05 till the financial crisis and global recession of 2008-09, which was facilitated both by a massive increase in industrial bank credit and significant foreign capital inflows. A similar private investment led boom has remained elusive under the NDA regime.

This testifies to the forgotten truth of political economy, that supposedly business friendly governments can deliver much wealth and profits for their cronies but are incapable of bringing about economy-wide structural changes and common prosperity.

Fiscal strains

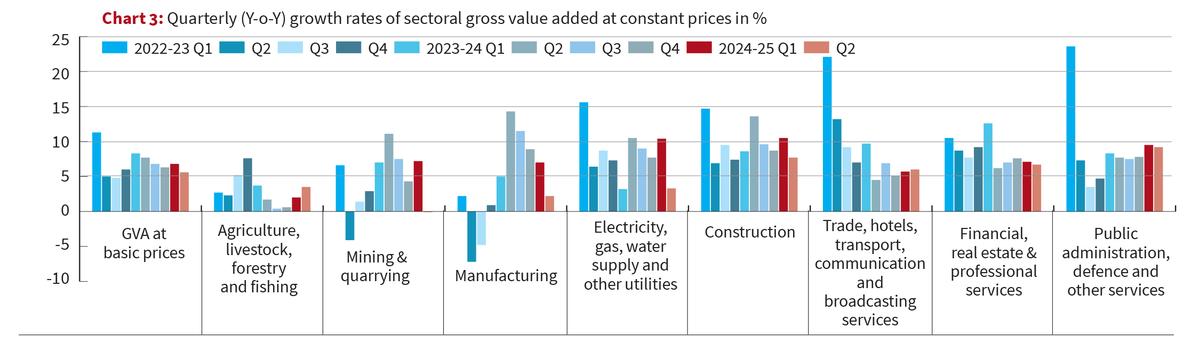

The more reliable supply side data on the Indian economy reflects a more sober picture of economic recovery since the pandemic and the nature of the slowdown that has set in. Quarterly Gross Value Added (GVA) growth on a year-on-year basis has been on a downward slide since 2023-24 (Chart 3). The agriculture sector continues to show cyclical fluctuations. After showing double-digit growth in the two quarters of 2023-24, the growth rate of manufacturing GVA has been on a downslide. Slowdown is visible not only in the mining, power and construction sectors but also in services like retail trade, transport, communications, finance and real estate.

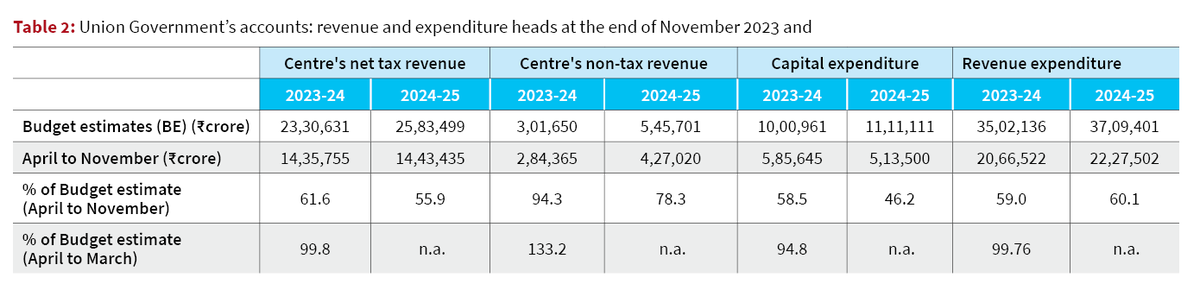

The only sector where GVA is projected to grow at a higher pace in 2024-25 than the previous year is public administration, defence and other services. This shows the crucial role of public spending in sustaining economic growth in the Indian economy. In this context, the monthly accounts of the Union Government further indicate that crucial revenue and expenditure targets set in the last Union Budget are likely to remain unachieved. While the windfall of a ₹2.11 trillion surplus transfer from the Reserve Bank of India has enabled the Union Government to mobilise over 78% of its non-tax revenue target for 2024-25 by November 2024, mobilisation of the Centre’s net tax revenues between April to November 2024 was only 56% of the budgetary target of ₹25.83 trillion (Table 2). This has led to spending less than half of the ₹11.11 trillion, budgeted as capex for 2024-25 till November 2024.

It is clear that economic slowdown has disrupted budgetary plans by slowing down tax revenue growth. Adhering to the fiscal consolidation path would imply a squeeze on public spending, including capital expenditure, which in turn would further aggravate the slowdown. Jettisoning fiscal rectitude altogether is also not feasible, given the already elevated levels of public debt and interest payments. The only way out appears to be a reworking of the revenue mobilisation strategy by enhancing taxation on wealth and profits in order to enhance capex and welfare spending.

Prasenjit Bose is an economist and activist. Soumyadeep Biswas is a data analyst at CPERD Pvt. Ltd.

Published – January 10, 2025 08:30 am IST