Riyadh:

After years of failing to secure a hajj visa, Yasser finally concluded he had no choice but to perform the holy pilgrimage illegally, a move he has now come to regret.

While he survived the gruelling annual rites that unfolded in extreme heat again this year, he has not seen his wife since Sunday and fears she is among the more than 1,000 reported fatalities — the majority unregistered Egyptians like himself.

“I have searched every single hospital in Mecca. She’s not there,” the 60-year-old retired engineer told AFP on Friday by phone from his hotel room, where he is reluctant to pack his wife’s suitcase in hopes she’ll be back to do it herself.

“I don’t want to believe in this possibility that she’s dead. Because if she’s dead, it’s the end of her life and also the end of my life.”

Egypt accounts for more than half of this year’s hajj fatalities — 658 out of more than 1,000 reported as of Friday by around 10 countries stretching from Senegal to Indonesia, according to an AFP tally.

An Arab diplomat told AFP that 630 of those 658 dead Egyptians were unregistered, meaning they could not rely on access to amenities meant to make the pilgrimage more bearable.

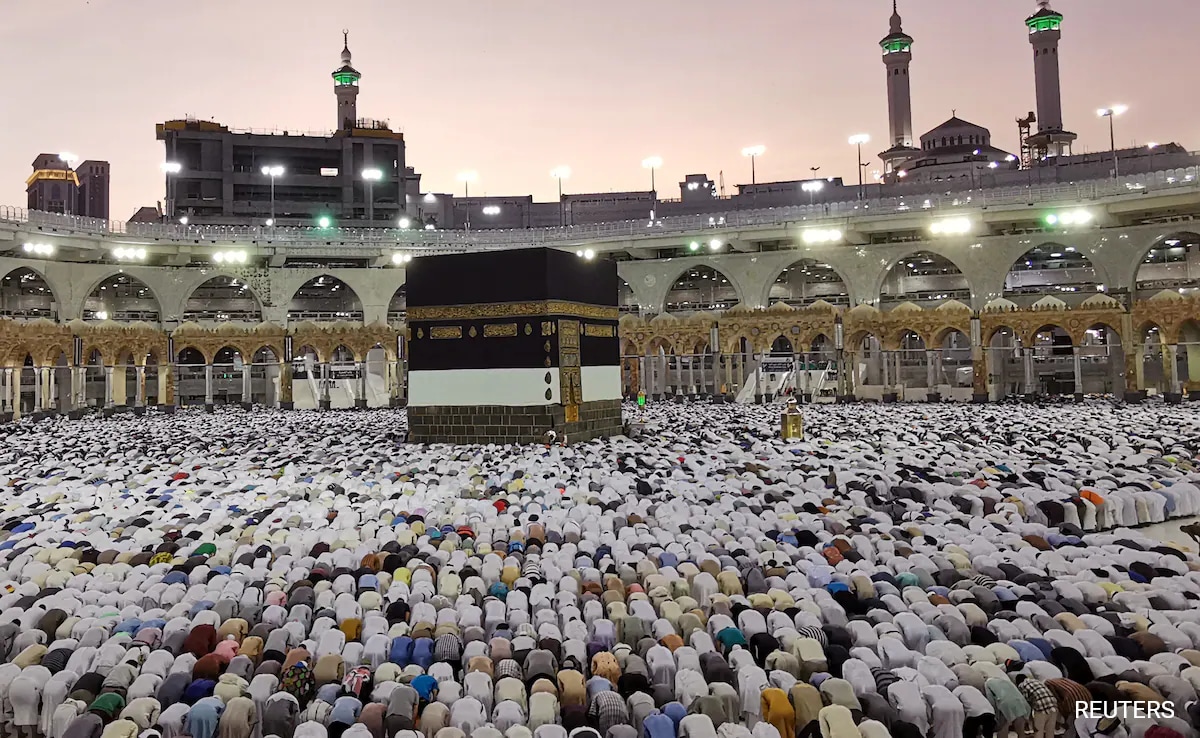

That included air-conditioned tents meant to offer some relief as temperatures soared to as high as 51.8 degrees Celsius (125 Fahrenheit) at the Grand Mosque in Mecca, the holiest site in Islam.

Saudi authorities have not responded to requests for comment about fatalities.

The health ministry reported more than 2,700 cases of “heat exhaustion” on Sunday alone, but has not updated the figure since then.

Off-the-books fees

The hajj, one of the five pillars of Islam, must be completed by all Muslims with the means at least once.

Yet official permits are allocated to countries through a quota system and distributed to individuals via a lottery.

Even for those who can obtain them, the steep costs make the irregular route — which costs thousands of dollars less — more attractive.

That is especially true since 2019 when Saudi Arabia began issuing general tourist visas, making it easier to travel to the Gulf kingdom.

But for Yasser, who declined to be identified by his full name because he is still in Saudi Arabia, the complications from being unregistered became clear as soon as he reached the country in May.

Well before the formal hajj rites began a week ago, some shops and restaurants refused service to visitors who could not show permits on the official hajj app, known as Nusuk.

Once the long days of walking and praying beneath the blazing sun got underway, he could not access official hajj buses — the only transportation around the holy sites — without paying exorbitant, off-the-books fees.

When heat drove him to exhaustion, he sought urgent care at a hospital in Mina but was turned away, he said, again for lack of a permit.

As their conditions worsened, Yasser and his wife Safaa lost each other in the crowds during the “stoning the devil” ritual in Mina.

Since then Yasser has repeatedly postponed their return flight home, hoping she will turn up.

“I will keep postponing it until I find her,” he said.

‘All of Egypt is sad’

Other unregistered Egyptian pilgrims interviewed by AFP this week described similar hardships — and similarly alarming sights along the hajj route as the heat’s toll mounted.

“There were dead bodies on the ground” in Arafat, Mina and on the way to Mecca, said Mohammed, 31, an Egyptian who lives in Saudi Arabia and who performed the hajj this year with his 56-year-old mother.

“I saw people suddenly collapse and die from exhaustion.”

Another Egyptian whose mother died on the pilgrimage route, and who declined to be identified by even a first name because she lives in Riyadh, said it was impossible to get her mother an ambulance.

An emergency vehicle only materialised after her mother was dead, taking the body to an unknown location.

“Until now my cousins in Mecca are still searching for the body of my mom,” she said.

“Don’t we have the right to get at last look at her before she is buried?”

Even some registered pilgrims struggled to access emergency services, pointing to a system that was overwhelmed, said Mustafa, whose elderly parents — who had their hajj permits — both died after becoming separated from younger relatives.

“We knew they were tired,” Mustafa told AFP by phone from Egypt. “They were walking very long distances and they couldn’t find water, and it was so hot.”

He had been looking forward to welcoming them home once they returned, but now his only solace comes from the fact they have been buried in the holy city of Mecca.

“Of course, we believe in what God has written for them…. but all of Egypt is sad,” he said.

“We’re never going to see them again.”

(Except for the headline, this story has not been edited by NDTV staff and is published from a syndicated feed.)

Waiting for response to load…